History of economic inequality

Economist Branko Milanović challenges this "naturalistic" approach of the evolution of inequality, deeming that there is nothing natural in it, but solely the product of industrial dispute.

American economist Thorstein Veblen states that first "barbarian" civilizations wage wars when meeting one another because of scarcity of ressources, which would have allowed the creation of a "predatory spirit".

[5] According to Stephen Rigby, an economist specializing in medieval economic history, the conservative ideology of 12th-, 13th- and 14th-century Europe warranted the level of inequality, in particular by denouncing sharp wage rises as a challenge to the feudal social order.

Knighthood was thus worthy of all their wealth, since they were morally and physically superior to the peasantry, being ready to defend the community by the sword, which would mean a purer soul.

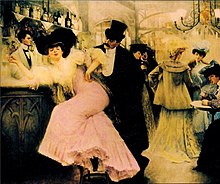

[7] Up to the beginning of the Gilded Age and the Industrial Revolution, the United States was a relatively equal country, thanks to a rapidly growing demography which prevented the emergence of rent.

While economic growth was dazzling thanks to the Industrial Revolution (it averaged 1.6%, compared with 0.3% in previous centuries), European societies were transformed into genuine rentier societies, with ever-increasing inequalities: Great Britain, Sweden and France became the three most unequal countries in history, with the top 10% of the population owning an average of 91%, 88% and 84% of national wealth respectively, while the bottom half of the population owned 1%, 1% and 2% of national wealth respectively.

Until the end of the 19th century, similar laws were passed in England, the United States, Denmark, Switzerland, Belgium, Italy and the Netherlands.

The figures revealed at the beginning of the twentieth century flabbergasted a majority of economists, statisticians and politicians: In 1919, Irving Fisher, a liberal, put the question of extreme inequality at the heart of current stakes in the United States, as this hyper-unequal distribution would threaten the very foundations of American society.

He proposed as a solution to tax direct inheritance by one-third, inheritance from grandparents by two-thirds, and inheritance from great-grandparents by the full amount; or the President of the French National Assembly, Joseph Caillaux, also a liberal, who confessed to being deeply shocked by the figures on the situation in France, and succeeded in convincing a majority of deputies to pass the first progressive income tax, before the Senate vetoed it in 1909:[15][16]Nous avons été conduits à croire, à dire que la France était le pays des petites fortunes, du capital émietté et dispersé jusqu'à l'infini.

If politicians allowed this increase in inequality, it was first and foremost because France was seen as a country of small property owners, and it was unacceptable to involve the State in the economy.

The Great Depression drastically changed many economists' and politicians' perceptions of capitalism, while the Second World War required massive reparations and reinvestment.

The result was the "Fordist compromise",[note 1] a high level of consumption spending, mass school enrolment and an easing of economic activity due to the collapse of a rent-based economy through inflation and bombing.

[19] The context of stagflation in the 70s and 80s seemed to call into question the usefulness of the welfare state, in favor of the emergence of a neoliberal movement led by economist Milton Friedman.

From the 1980s onwards, this led to lower taxes and the privatization of public enterprises in developed countries, notably under the impetus of Ronald Reagan in the US, Margaret Thatcher in the UK, Helmut Schmidt in Germany and Jacques Delors in France.

[note 2][4] Yet according to Thomas Piketty, there is no statistically significant evidence to suggest that this rise in inequality and lower taxation of the wealthiest has boosted growth since the 1980s.

[23] Thomas Piketty nevertheless qualifies these figures: a large proportion of inequalities in the USSR can be found in payment in kind, notably in the form of gifts of housing, passes... in short, privileges that are difficult to quantify.

[26][27] Thomas Piketty argues that voucher privatization prompted wealthy landowners to buy up a huge number of property rights, thereby rapidly increasing the level of inequality in post-Soviet countries, a policy which is at the root of the Russian oligarchy.

[22][37][38][39][40] Thomas Piketty laments not so much our current situation as the trend we're heading towards; as the United States has demonstrated, there is a great risk that developed countries will massively apply liberal policies in the future until they return to a level of inequality close to that of the early 20th century, which will make it all the more difficult for developing countries to create a strong state to invest in human capital.

[19] Artificial intelligence is also likely to significantly increase economic inequality, as school enrolment has stopped growing to the benefit of wealthy wage earners and digital companies.