History of equity and trusts

The origin of the trust has to be traced to medieval England,[2] where a distinction arose between the 'regular "course of the common law" ' and the practices and rulings that the Lord Chancellor gave.

[3] Despite this, the Kings were accepted to retain the right to administer justice in special cases where common law was 'deficient' and the matter in question did not involve 'life, limb or property'.

[2] It is important to remark that originally they were seen as merely addressing particular cases and could neither affect parties not named in the decrees the Chancellor gave nor change the law.

[5] While the Common Law almost invariably awarded money damages, Equity was able to force defendants to act a particular way on penalty of being imprisoned for contempt court.

[8] This oath of poverty, as confirmed by the papal bull Quo elongati (1230), did not prevent them from enjoying the benefits of said land like rents and free accommodation.

This was particularly important as the King had the right to charge a fee for issuing a licence that would allow a donor to gift land to the Church.

Indeed, as Baker notes in 1375, a group of feoffees (i.e. those to whom land was transferred to hold for the benefit of another) were excommunicated for breaching the conditions of the use they were supposed to execute.

[12] Uses were a matter of good conscience, it was the Court of Chancery, however, it was suited to pick up the mantle of enforcing the cestui que use's moral right, creating the modern trust in the process.

[14] This was achieved by a dying testator conveying land to feoffees, which could be friends, legal advisers or other local gentry, to the use of executing his will.

[17] In 1529, Henry VIII proposed a bill that would restore feudal incidents where land had been conveyed to the use of executing the landowners will but only at one third of the levels that the Common Law demanded.

The House of Commons rejected the bill in 1531, at which point the King threatened that if they would not accept his proposal he would seek to enforce his feudal rights as far as the Law allowed.

An opportunity to restore the full force of the English feudal law of inheritance (and thus the King's incidents) came when Lord Dacre died in 1533.

This was an uprising that started in Yorkshire and spread across the North which sought to reverse some of Henry VIII's most controversial policies, such as the Dissolution of the monasteries, the break with the Roman Catholic Church, but also the Statute of Uses.

While the Pilgrimage was itself unsuccessful, the idea that a loophole or work around the prohibition of wills of land could be found began to take hold in legal circles.

Under either of these arrangements the Statute would execute the initial Use (i.e. either X or Y would immediately stand seised to the use of B), but the second Use was not, allowing therefore for the creation of Uses of land so long as an intermediary was inserted before the intended beneficiary.

In that case the dowager Duchess of Suffolk had fled to Poland to avoid persecution as a Protestant during the reign of Mary and had conveyed land to a lawyer 'to his use' but secretly on trust to be reconveyed to her.

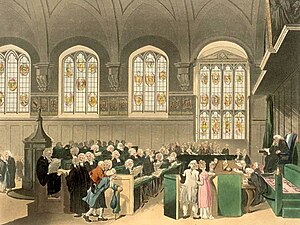

Around this time the jurisdiction also came under increased scrutiny due to a perception that deciding cases according to the conscience of one man was arbitrary and contrary to the Common Law.

It was contrary to both a 1597 decision of all the Common Law judges sitting in Exchequer Chamber[34][35] and to a statute from the reign of Henry IV.

[36] Thus, Edward Coke, then Chief Justice of the King's Bench (appointed 1613), began releasing, through writs of habeas corpus those that Ellesmere had committed to prison for contempt of Court for enforcing their common law judgements.

The same title had already been determined by a Common Law court in a previous case[note 6] and so the Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge, a man called Gooch, was imprisoned by the Lord Chancellor for refusing to answer to the proceedings in Chancery.

The matter was resolved when two plaintiffs brought prosecutions against Chancery officials and lawyers (including some close to Ellesmere) for the crime of praemunire.

[40] Coke would be dismissed as Chief Justice, and indeed as a judge altogether a few months afterwards for a separate but similar dispute about whether the King was above the law.

[41] Ellesmere's death in 1617 and his replacement with Francis Bacon sought to foster better relations with the Common Law judges, preventing the open hostility from arising again.

Thus even if the King James's ruling of 1616 would come to be seen as illegal,[42] the supremacy of Equity would eventually prevail when the different jurisdictions were amalgamated in the 19th Century into what today is are Senior Courts of England and Wales.

[49] Part of the background to and causes of the English Civil War was the perceived sense that the King was arbitrary and was ruling despotically.

Likewise, since Chancery officials were not paid a salary but rather made their living from fees, there was no incentive to process cases efficiently.

Instead of one Lord Chancellor, Cromwell and the House of Commons appointed several Commissioners of the Great Seal of England and tasked them with reforming the court.

Despite the fact that Parliament, in the later years of the Commonwealth, would once again consider how to best reform the Chancery, the Monarchy and thus the old officials and most of their practices were restored before they could settle on a satisfactory scheme.

While the driving force behind Clarendon's reforms was to protect the interests of officeholders,[56] there was some initial success at improving the efficiency of the court.

[57] Partly as a reaction to the increased amount of work, the House of Lords claimed an appellate jurisdiction from the Court of Chancery.