United Kingdom company law

Tracing their modern history to the late Industrial Revolution, public companies now employ more people and generate more of wealth in the United Kingdom economy than any other form of organisation.

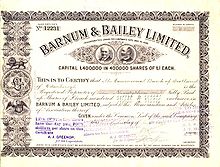

The United Kingdom was the first country to draft modern corporation statutes,[1] where through a simple registration procedure any investors could incorporate, limit liability to their commercial creditors in the event of business insolvency, and where management was delegated to a centralised board of directors.

The South Sea Company's monopoly rights were supposedly backed by the Treaty of Utrecht, signed in 1713 as a settlement following the War of Spanish Succession, which gave the United Kingdom an assiento to trade, and to sell slaves in the region for thirty years.

Without cohesive regulation, undercapitalised ventures like the proverbial "Anglo-Bengalee Disinterested Loan and Life Assurance Company" promised no hope of success, except for richly remunerated promoters.

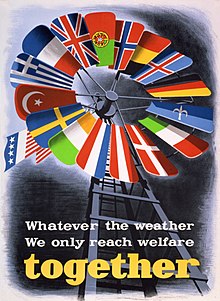

In 1977, the government's Bullock Report proposed reform to allow employees to participate in selecting the board of directors, as was happening across Europe, exemplified by the German Codetermination Act 1976.

Just as it is possible for two contracting parties to stipulate in an agreement that one's liability will be limited in the event of contractual breach, the default position for companies can be switched back so that shareholders or directors do agree to pay off all debts.

[35] The 2006 reforms have also clarified the legal position that if a company does have limited objects, an ultra vires act will cause the directors to have breached a duty to follow the constitution under section 171.

As a general rule, third parties need not be concerned with constitutional details conferring power among directors or employees, which may only be found by laboriously searching the register at Companies House.

[41] But despite strict liability in tort, civil remedies are in some instances insufficient to provide a deterrent to a company pursuing business practices that could seriously injure the life, health and environment of other people.

Even with additional regulation by government bodies, such as the Health and Safety Executive or the Environment Agency, companies may still have a collective incentive to ignore the rules in the knowledge that the costs and likelihood of enforcement is weaker than potential profits.

Criminal sanctions remain problematic, for instance if a company director had no intention to harm anyone, no mens rea, and managers in the corporate hierarchy had systems to prevent employees committing offences.

This creates a criminal offence for manslaughter, meaning a penal fine of up to 10 per cent of turnover against companies whose managers conduct business in a grossly negligent fashion, resulting in deaths.

Rejecting the claim, and following the reasoning in Jones v Lipman,[51] the Court of Appeal emphasised that the US subsidiary had been set up for a lawful purpose of creating a group structure overseas, and had not aimed to circumvent liability in the event of asbestos litigation.

The potentially unjust result for tort victims, who are unable to contract around limited liability and may be left only with a worthless claim against a bankrupt entity, has been changed in Chandler v Cape plc so that a duty of care may be owed by a parent to workers of a subsidiary regardless of separated legal personality.

In 1999, in Centros Ltd v Erhvervs- og Selskabsstyrelsen[59] the European Court of Justice held that a Danish minimum capital rule for private companies was a disproportionate infringement of the right of establishment for businesses in the EU.

[70] It is generally the decision of the board of directors, affirmed by a shareholder resolution, whether to declare a dividend or perhaps simply retain the earnings and invest them back into the business to grow and expand.

[73] A general principle, however, recently expounded in Progress Property Co Ltd v Moorgarth Group Ltd is that if a transaction is negotiated in good faith and at arm's length, then it may not be unwound,[74] and this is apparently so even if it means that creditors have been "ripped off".

For example, in It's A Wrap (UK) Ltd v Gula[77] the directors of a bankrupt company argued that they had been unaware that dividend payments they paid themselves were unlawful (as there had not in fact been profits) because their tax advisers had said it was okay.

This makes recommendations about the structure, accountability and remuneration of the board of directors in listed companies, and was developed after the Polly Peck, BCCI and Robert Maxwell scandals led to the Cadbury Report of 1992.

However, put broadly corporate governance in UK law focuses on the relative rights and duties of directors, shareholders, employees, creditors and others who are seen as having a "stake" in the company's success.

UK rules usually focus on protecting shareholders or the investing public, but above the minimum, company constitutions are essentially free to allocate rights and duties to different groups in any form desired.

Even if companies' articles are silent on an issue, the courts will construe the gaps to be filled with provisions consistent with the rest of the instrument in its context, as in the old case of Attorney General v Davy where Lord Hardwicke LC held that a simple majority was enough for the election of a chaplain.

[119] Categories of important decisions, such as large asset sales,[120] approval of mergers, takeovers, winding up of the company, any expenditure on political donations,[121] share buybacks, or a (for the time being) non-binding say on pay of directors,[122] are reserved exclusively for the shareholder body.

[124] Shareholding institutions, who are entered on the share registers of public companies on the London Stock Exchange, are mainly asset managers and they infrequently exercise their governance rights.

In the 1977 Report of the committee of inquiry on industrial democracy[137] the Government proposed, in line with the new German Codetermination Act 1976, and mirroring an EU Draft Fifth Company Law Directive, that the board of directors should have an equal number of representatives elected by employees as there were for shareholders.

The court must refuse permission for the claim if the alleged breach has already been validly authorised or ratified by disinterested shareholders,[171] or if it appears that allowing litigation would undermine the company's success by the criteria laid out in section 172.

This residual protection for minorities was developed by the Court of Appeal in Allen v Gold Reefs of West Africa Ltd,[180] where Sir Nathaniel Lindley MR held that shareholders may amend a constitution by the required majority so long as it is "bona fide for the benefit of the company as a whole".

In practice, large companies frequently give directors ad hoc authority to disapply pre-emption rights, but within the scope of a 'Statement of Principles' issued by asset managers.

[207] Even with the UK's non-frustration principle directors always still have the option to persuade their shareholders through informed and reasoned argument that the share price offer is too low, or that the bidder may have ulterior motives that are bad for the company's employees, or for its ethical image.

Originally established in 1968 as a private club that self-regulated its members' practices, was held in R (Datafin plc) v Takeover Panel[218] to be subject to judicial review of its actions where decisions are found to be manifestly unfair.