History of geomagnetism

It encompasses the history of navigation using compasses, studies of the prehistoric magnetic field (archeomagnetism and paleomagnetism), and applications to plate tectonics.

A modern experimental approach to understanding the Earth's field began with de Magnete, a book published by William Gilbert in 1600.

In his Natural History, Pliny the Elder recounts a legend about a Magnes the shepherd on the island of Crete whose iron-studded boots kept sticking to the path.

This theory can be found in the writings of Pliny the Elder and Aristotle, who claimed that Thales attributed a soul to the magnet.

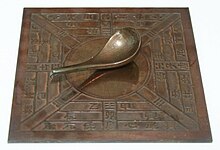

[2] In China, a similar life force, or qi, was believed to animate magnets, so the Chinese used early compasses for feng shui.

One belief, dating back to Pliny, was that fumes from eating garlic and onions could destroy the magnetism in a compass, rendering it useless.

[6] In China, the horizontal direction was measured as early as the fourth century BC, and the existence of declination first recognized in 1088.

While his contemporary Roger Bacon is reputed to observe that compasses deviated from true north, the idea of magnetic declination was only gradually accepted.

He created a compass in which the needle was floated in a goblet of water, attached to a cork to make it neutrally buoyant.

Norman also created a dip circle, a compass needle pivoted about a horizontal axis, to measure the effect.

These theories required that magnets point at (or very close to) true north, so they ran into difficulty when the existence of declination was accepted.

Gilbert distinguishes between magnetism and static electricity (the latter being induced by rubbing amber) and reports many experiments with both (some dating back to Peregrinus).

[11][12] In the late 1590s Henry Briggs, a professor of geometry at Gresham College in London, had published a table of magnetic inclination with latitude for the earth.

Based on the declinations that were known at the time, he proposed that the continents, because of their raised topography, formed centers of attraction that made compass needles deviate.

A Jesuit monk, Niccolò Cabeo, later took a leaf from Gilbert's book and showed that, if the topography was on the correct scale for the Earth, the differences between the highs and lows would only be about one tenth of a millimeter.

He dismissed the prevailing Ptolemaic model of the universe, in which the planets and stars are organized in a series of concentric shells rotating about the Earth, on the grounds that the speeds involved would be absurdly large ("there cannot be diurnal motion of infinity").

Some obscure reasoning led to the peculiar conclusion that a terella, if freely suspended, would orient itself in the same direction as the Earth and rotate daily.

Both Kepler and Galileo would adopt Gilbert's idea of magnetic attraction between heavenly bodies, but Newton's law of universal gravitation would render it obsolete.

[2][7][12] Le Nautonier tried to sell his model to Henry IV, and his son to the English leader Oliver Cromwell, both without success.

It was widely criticized, with Didier Dounot concluding that the work was based on "unfounded assumptions, errors in calculation and data manipulation".

The reality of geomagnetic secular variation was rapidly accepted in England, where Gellibrand had a high reputation, but in other countries it was met with skepticism until it was confirmed by further measurements.

[2][14] The observations of Gellibrand inspired extensive efforts to determine the nature of variation - global or local, predictable or erratic.

His model, which involved a precessing dipole, was strongly criticized by a royal commission, but it continued to be published in navigational instruction manuals for decades.

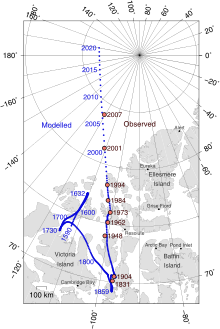

In 1831 James Clark Ross from the ship Victory first located the Earth's magnetic North Pole on the west coast of the Boothia Peninsula (Arctic Archipelago).

In 1842 the Antarctic Ross expedition inferred the position of the South Magnetic Pole, which was not formally located until the twentieth century.

Since then, the North magnetic pole has migrated on a north-northwest direction, towards Siberia, and since 2017 has been located a few hundred kilometres into the Arctic Ocean.

Owing to liquid motion of the Earth's core, the actual magnetic poles are constantly moving (secular variation).

The poles also daily swing in an oval of around 80 km (50 miles) in diameter due to solar wind deflecting the magnetic field.

[18] Observed variations in magnetic direction, strength and dip led to determinations by Alexander von Humboldt, Carl Friedrich Gauss and Edward Sabine that the Earth's magnetic field should be systematically surveyed and monitored globally to perhaps reveal important geophysical aspects of the planet.