History of optics

[2] In the 4th century BC Chinese text, credited to the philosopher Mozi, it is described how light passing through a pinhole creates an inverted image in a "collecting-point" or "treasure house".

Euclid did not define the physical nature of these visual rays but, using the principles of geometry, he discussed the effects of perspective and the rounding of things seen at a distance.

Where Euclid had limited his analysis to simple direct vision, Hero of Alexandria (c. AD 10–70) extended the principles of geometrical optics to consider problems of reflection (catoptrics).

[6] Hero demonstrated the equality of the angle of incidence and reflection on the grounds that this is the shortest path from the object to the observer.

"[10] This theory of the active power of rays had an influence on later scholars such as Ibn al-Haytham, Robert Grosseteste and Roger Bacon.

[11] Ibn Sahl, a mathematician active in Baghdad during the 980s, is the first Islamic scholar known to have compiled a commentary on Ptolemy's Optics.

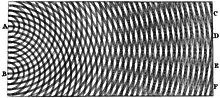

[13] He used his law of refraction to compute the shapes of lenses and mirrors that focus light at a single point on the axis.

[21] Abu 'Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Ma'udh, who lived in Al-Andalus during the second half of the 11th century, wrote a work on optics later translated into Latin as Liber de crepisculis, which was mistakenly attributed to Alhazen.

[22] In the late 13th and early 14th centuries, Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi (1236–1311) and his student Kamāl al-Dīn al-Fārisī (1260–1320) continued the work of Ibn al-Haytham, and they were among the first to give the correct explanations for the rainbow phenomenon.

[23] The English bishop Robert Grosseteste (c. 1175–1253) wrote on a wide range of scientific topics at the time of the origin of the medieval university and the recovery of the works of Aristotle.

In his optical writings (the Perspectiva, the De multiplicatione specierum, and the De speculis comburentibus) he cited a wide range of recently translated optical and philosophical works, including those of Alhacen, Aristotle, Avicenna, Averroes, Euclid, al-Kindi, Ptolemy, Tideus, and Constantine the African.

Although he was not a slavish imitator, he drew his mathematical analysis of light and vision from the writings of the Arabic writer, Alhacen.

[27] Note that Bacon's optical use of the term species differs significantly from the genus/species categories found in Aristotelian philosophy.

Several later works, including the influential A Moral Treatise on the Eye (Latin: Tractatus Moralis de Oculo) by Peter of Limoges (1240–1306), helped popularize and spread the ideas found in Bacon's writings.

[28] Another English Franciscan, John Pecham (died 1292) built on the work of Bacon, Grosseteste, and a diverse range of earlier writers to produce what became the most widely used textbook on optics of the Middle Ages, the Perspectiva communis.

[29] Like his predecessors, Witelo (born circa 1230, died between 1280 and 1314) drew on the extensive body of optical works recently translated from Greek and Arabic to produce a massive presentation of the subject entitled the Perspectiva.

1310) was among the first in Europe to provide the correct scientific explanation for the rainbow phenomenon,[31] as well as Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi (1236–1311) and his student Kamāl al-Dīn al-Fārisī (1260–1320) mentioned above.

In it, Kepler described the inverse-square law governing the intensity of light, reflection by flat and curved mirrors, and principles of pinhole cameras, as well as the astronomical implications of optics such as parallax and the apparent sizes of heavenly bodies.

Astronomiae Pars Optica is generally recognized as the foundation of modern optics (though the law of refraction is conspicuously absent).

These included the Opera reliqua (also known as Christiani Hugenii Zuilichemii, dum viveret Zelhemii toparchae, opuscula posthuma) and the Traité de la lumière.

"[35] Newton was also the first to describe the use of prisms as beam expanders and multiple-prism arrays, which would later become integral to the development of early tunable lasers.

[40] The so-called Nimrud lens, a rock crystal artifact dated to the 7th century BCE, might have been used as a magnifying glass, although it could have simply been a decoration.

[41][42][43][44][45] The earliest written record of magnification dates back to the 1st century CE, when Seneca the Younger, a tutor of Emperor Nero, wrote: "Letters, however small and indistinct, are seen enlarged and more clearly through a globe or glass filled with water.

[47] Ibn al-Haytham (Alhacen) wrote about the effects of pinhole, concave lenses, and magnifying glasses in his 11th century Book of Optics (1021 CE).

Often used by monks to assist in illuminating manuscripts, these were primitive plano-convex lenses, initially made by cutting a glass sphere in half.

[52] The earliest known examples of compound microscopes, which combine an objective lens near the specimen with an eyepiece to view a real image, appeared in Europe around 1620.

As laser science needed good theoretical foundations, and also because research into these soon proved very fruitful, interest in quantum optics rose.

In 1977, Kimble et al. demonstrated the first source of light which required a quantum description: a single atom that emitted one photon at a time.

At the same time, development of short and ultrashort laser pulses—created by Q-switching and mode-locking techniques—opened the way to the study of unimaginably fast ("ultrafast") processes.

Applications for solid state research (e.g. Raman spectroscopy) were found, and mechanical forces of light on matter were studied.