History of paper

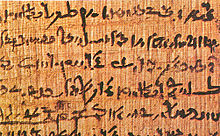

The first paper-like plant-based writing sheet was papyrus in Egypt, but the first true papermaking process was documented in China during the Eastern Han period (25–220 AD), traditionally attributed to the court official Cai Lun.

[11]Archaeological evidence of papermaking predates the traditional attribution given to Cai Lun,[12] an imperial eunuch official of the Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), thus the exact date or inventor of paper cannot be deduced.

After the Tang dynasty, rattan paper declined because it required specific growing areas, was slow in growth, and had a long regeneration cycle.

[14]Among the earliest known uses of paper was padding and wrapping delicate bronze mirrors according to archaeological evidence dating to the reign of Emperor Wu of Han from the 2nd century BCE.

[22] In 589, the Chinese scholar-official Yan Zhitui (531–591) wrote: "Paper on which there are quotations or commentaries from Five Classics or the names of sages, I dare not use for toilet purposes".

[22] During the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), the first well-documented European in Medieval China, the Venetian merchant Marco Polo remarked how the Chinese burned paper effigies shaped as male and female servants, camels, horses, suits of clothing and armor while cremating the dead during funerary rites.

[31]However, despite the initial advantage afforded to China by the paper medium, by the 9th century its spread and development in the Middle East had closed the gap between the two regions.

After 1700, libraries in North America also began to overtake those of China, and toward the end of the century, Thomas Jefferson's private collection numbered 4,889 titles in 6,487 volumes.

[40] A Persian geography book written by an unknown author in the 10th century, Hodud al-Alam, is the oldest known manuscripts mentioning papermaking industry in Samarkand.

[44] In 1035 a Persian traveler, Nasir Khusraw, visiting markets in Cairo noted that vegetables, spices and hardware were wrapped in paper for the customers.

[46] The expansion of public and private libraries and illustrated books within Islamic lands was one of the notable outcomes of the drastic increase in the availability of paper.

[47] However, paper was still an upmarket good given the remarkable required inputs, e.g. primary materials and labours, to produce the item in the absence of advanced mechanical machinery.

Papers were typically named based on several criteria: Bast (hemp and flax), cotton, and old rags and ropes were the major input materials for producing the pulp.

This papermaking instruction or recipe is a chapter under the title of al-kâghad al-baladî (local paper) from the manuscript of al-Mukhtara'fî funûn min al-ṣunan attributed to al-Malik al-Muẓaffar, a Yemeni ruler of Rasulids.

During the pulping stage, the beaten fibres were transformed into different sizes of Kubba (cubes) which they were used as standard scales to manufacture a certain number of sheets.

Near Eastern paper is mainly characterized by sizing with a variety of starches such as rice, katira (gum tragacanth), wheat, and white sorghum.

Production began in Baghdad, where a method was invented to make a thicker sheet of paper, which helped transform papermaking from an art into a major industry.

[67] Thin sheets of birch bark and specially treated palm-leaves remained the preferred writing surface for literary works through late medieval period in most of India.

[65] This exchange is evidenced by the Indian talapatra binding methods that were adopted by Chinese monasteries such as at Tunhuang for preparing sutra books from paper.

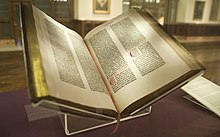

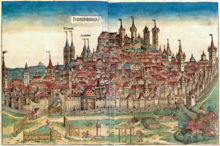

Papermaking then spread further northwards, with evidence of paper being made in Troyes, France by 1348, in Holland sometime around 1340–1350, and in Nuremberg, Germany by 1390 in a mill set up by Ulman Stromer.

The Fabriano used glue obtained by boiling scrolls or scraps of animal skin to size the paper; it is suggested that this technique was recommended by the local tanneries.

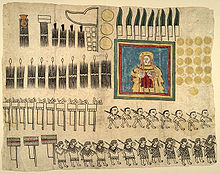

The Otomi people in Mexico still make amate today but have trouble meeting demand due to a dwindling supply of fig and mulberry trees, which are in danger of extinction.

However, by the mid-19th century the sulfite process had begun to proliferate in other regions with better access to wood pulp, and by 1880, America had become the largest producer of paper goods in the world.

[109] A decree by the Christian king Peter III addresses the establishment of a royal "molendinum", a proper hydraulic mill, in the paper manufacturing centre of Xàtiva.

With the help particularly of Bryan Donkin, a skilled and ingenious mechanic, an improved version of the Robert original was installed at Frogmore Paper Mill, Hertfordshire, in 1803, followed by another in 1804.

[119] Together with the invention of the practical fountain pen and the mass-produced pencil of the same period, and in conjunction with the advent of the steam driven rotary printing press, wood based paper caused a major transformation of the 19th-century economy and society in industrialized countries.

Cheap wood based paper also meant that keeping personal diaries or writing letters became possible[clarification needed] and so, by 1850, the clerk, or writer, ceased to be a high-status job.

[citation needed] Early wood-based paper deteriorated as time passed, meaning that much of the output of newspapers and books from this period either has disintegrated or is in poor condition; some has been photographed or digitized (scanned).

All our evidence points to non-hydraulic hand production, however, at springs away from rivers which it could pollute.European papermaking differed from its precursors in the mechanization of the process and in the application of water power.

Jean Gimpel, in The Medieval Machine (the English translation of La Revolution Industrielle du Moyen Age), points out that the Chinese and Muslims used only human and animal force.