History of psychiatry

[4] During the 5th century BCE, mental disorders, especially those with psychotic traits, were considered supernatural in origin,[5] a view which existed throughout ancient Greece and Rome.

[10][11][12] Specialist hospitals were built in medieval Europe from the 13th century to treat mental disorders but were utilized only as custodial institutions and did not provide any type of treatment.

[13] During the early modern period, mentally ill people were often held captive in cages or kept up within the city walls, or they were compelled to amuse members of courtly society.

[14] From the 13th century onwards, sick and poor people were kept in newly founded ecclesiastical hospitals, such as the "Spittal sente Jorgen" erected in 1212 in Leipzig, in Saxony, Germany.

[15] Inmates who were deemed dangerous or disturbing were chained, but Bethlem was an otherwise open building for its inhabitants to roam around its confines and possibly throughout the general neighborhood in which the hospital was situated.

[17]: 155 [18]: 27 In 1621, Oxford University mathematician, astrologer, and scholar Robert Burton published one of the earliest treatises on mental illness, The Anatomy of Melancholy, What it is: With all the Kinds, Causes, Symptomes, Prognostickes, and Several Cures of it.

[19] In 1656, Louis XIV of France created a public system of hospitals for those with mental disorders, but as in England, no real treatment was applied.

[21] In Saxony, a new social policy was implemented at the beginning of the 18th century in which criminals, prostitutes, vagrants, orphans, and the mentally ill were incarcerated and re-educated in the concepts of the Enlightenment.

As a result, a variety of jails, approved schools, and insane asylums were constructed, including the hospital "Chur-Sachisches Zucht-Waysen und Armen-Haus" in Waldheim in 1716, which was the first governmental institution dedicated to the care of the mentally ill on the German territory.

Battie argued for a tailored management of patients entailing cleanliness, good food, fresh air, and distraction from friends and family.

[5] The introduction of moral treatment was initiated independently by the French doctor Philippe Pinel and the English Quaker William Tuke.

Pussin and Pinel's approach was seen as remarkably successful and they later brought similar reforms to a mental hospital in Paris for female patients, La Salpetrière.

There was an emphasis on the selection and supervision of attendants in order to establish a suitable setting to facilitate psychological work, and particularly on the employment of ex-patients as they were thought most likely to refrain from inhumane treatment while being able to stand up to pleading, menaces, or complaining.

[26] William Tuke led the development of a radical new type of institution in northern England, following the death of a fellow Quaker in a local asylum in 1790.

[27]: 84–85 [28]: 30 [29] In 1796, with the help of fellow Quakers and others, he founded the York Retreat, where eventually about 30 patients lived as part of a small community in a quiet country house and engaged in a combination of rest, talk, and manual work.

Rejecting medical theories and techniques, the efforts of the York Retreat centered around minimizing restraints and cultivating rationality and moral strength.

At the Lincoln Asylum in England, Robert Gardiner Hill, with the support of Edward Parker Charlesworth, pioneered a mode of treatment that suited "all types" of patients, so that mechanical restraints and coercion could be dispensed with — a situation he finally achieved in 1838.

[31][32] Scotland's Edinburgh medical school of the eighteenth century developed an interest in mental illness, with influential teachers including William Cullen (1710–1790) and Robert Whytt (1714–1766) emphasising the clinical importance of psychiatric disorders.

Some of the medical students, including William A. F. Browne (1805–1885), responded very positively to this materialist conception of the nervous system and, by implication, of mental disorder.

Parliamentary Committees were established to investigate abuses at private madhouses like Bethlem Hospital - its officers were eventually dismissed and national attention was focused on the routine use of bars, chains and handcuffs and the filthy conditions the inmates lived in.

[33] The commission was made up of eleven Metropolitan Commissioners who were required to carry out the provisions of the Act;[34] the compulsory construction of asylums in every county, with regular inspections on behalf of the Home Secretary.

[54]: 221 While Kraepelin tried to find organic causes of mental illness, he adopted many theses of positivist medicine, but he favoured the precision of nosological classification over the indefiniteness of etiological causation as his basic mode of psychiatric explanation.

[55] Following Sigmund Freud's pioneering work, ideas stemming from psychoanalytic theory also began to take root in psychiatry.

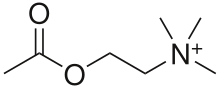

Psychopharmacology became an integral part of psychiatry starting with Otto Loewi's discovery of the neuromodulatory properties of acetylcholine; thus identifying it as the first-known neurotransmitter.

[69] Based on his participant observation field work, the book developed the theory of the "total institution" and the process by which it takes efforts to maintain predictable and regular behavior on the part of both "guard" and "captor".

[70] At the same time, academic psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Thomas Szasz began publishing articles and books that were highly critical of psychiatry and involuntary treatment, including his best-known work The Myth of Mental Illness in 1961.

[74] Critics such as Robert Spitzer placed doubt on the validity and credibility of the study, but did concede that the consistency of psychiatric diagnoses needed improvement.

[75] Spitzer went on to chair the writing of the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which aimed to improve reliability by emphasizing measurable symptoms.