Religion in Indonesia

[7] Blasphemy is a punishable offence (since 1965, see § History) and the Indonesian government has a discriminatory attitude towards its numerous tribal religions, atheist and agnostic citizens.

[15] From 1975 to 2017, Indonesian law mandated that its citizens possess an identity card indicating their religious affiliation, which could be chosen from a selection of those six recognised religions.

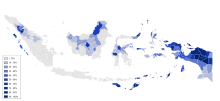

[17] According to Ministry of Home Affairs data in 2023, 87.06% of Indonesians identified themselves as Muslim (with Sunnis about 99%,[18] Shias about 1%[19]), 10.47% Christians (7.41% Protestants, 3.06% Roman Catholic), 1.68% Hindu, 0.71% Buddhists, 0.03% Confucians and 0.05% others.

[21] Historically, immigration from the Indian subcontinent, mainland China, Portugal, the Arab world, and the Netherlands has been a significant contributor to the diversity of religion and culture within the archipelago.

Coming from Gujarat, India[22] (some scholars also propose the Arabian and Persian theories[26]), Islam spread through the west coast of Sumatra and then developed to the east in Java.

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) regulated the missionary work so it could serve its own interests and focused it to the eastern, Animist part of the archipelago, including Maluku, North Sulawesi, Nusa Tenggara, Papua and Kalimantan.

[30] The Sukarno era was characterised by a "distrust" between religion and the state;[31] an example of this was the passing of a presidential edict in late January 1965 (still completely in force today and will be partially repealed starting 2026) which alongside attempting to ban religious blasphemy also explicitly declared in its explanatory memorandum that:[11] The religions professed by citizens in Indonesia are: Islam, Christianity [Catholicism and Protestantism], Hinduism, Buddhism, and Kong Fuzi (Confucianism).

[36] Over the 15th and 16th century, the spread of Islam accelerated via the missionary work of Maulana Malik Ibrahim (also known as Sunan Gresik, originally from Samarkand, at the time part of the Persian empire) in Sumatra and Java and Admiral Zheng He (also known as Cheng Ho, from China) in north Java, as well as campaigns led by sultans that targeted Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms and various communities, with each trying to carve out a region or island for control.

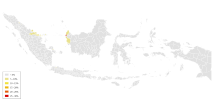

[49] The earliest history of Ahmadi Muslims in the archipelago dates back to the summer of 1925, when roughly two decades before the Indonesian revolution, a missionary of the Community, Rahmat Ali, stepped in Sumatra and established the movement with 13 devotees in Tapaktuan, Aceh.

One Catholic priest was executed for celebrating Mass in prison during Jan Pieterszoon Coen's tenure as Governors of the Dutch East Indies.

[52][53] In present-day Flores, the royal house of Larantuka formed the only native Catholic kingdom in Southeast Asia around the 16th century, with the first king named Lorenzo.

On 15 December 1904, a group of 178 Javanese were baptised at Semagung, Muntilan, district Magelang, Central Java, near the border of the Special Region of Yogyakarta.

[57] In September 2024, as part of his Apostolic Journey, Pope Francis visited Indonesia, which he will also attend neighboring countries such as Papua New Guinea, East Timor, and Singapore.

In some parts of the country, entire villages belong to a distinct denomination, such as Adventism, the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel, Lutheran, Presbyterian or the Salvation Army (Bala Keselamatan) depending on the success of missionary activity.

[78] Hindu culture and religion arrived in the archipelago around the 2nd century CE, which later formed the basis of several Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms such as Kutai, Mataram, and Majapahit.

Some historical heritage monuments can be found in Indonesia, including the Borobudur Temple in Yogyakarta and statues or prasasti (inscriptions) from the earlier history of Buddhist empires.

[92] Following the downfall of President Sukarno in the mid-1960s and the mandatory policy of having a religion,[93] founder of Perbuddhi (Indonesian Buddhists Organisation), Bhikku Ashin Jinarakkhita, proposed that there was a single supreme deity, Sanghyang Adi Buddha.

These spirits are believed to inhabit natural objects, human beings, artefacts, and grave sites of the important wali (Muslim saints).

Illness and other misfortunes are traced to such spirits, and if sacrifices or pilgrimages fail to placate angry deities, the advice of a dukun or healer is sought.

[103] The Kejawèn have no certain prophet, a sacred book, nor distinct religious festivals and rituals; it has more to do with each adherent's internalised transcendental vision and beliefs in their relations with others and with the supreme being.

This loosely organised current of thought and practice was legitimised in the 1945 constitution and, in 1973, when it was recognised as Kepercayaan kepada Tuhan Yang Maha Esa (Believer of One Supreme God) that somewhat gain the status as one of the agama.

The basis of Subud is a spiritual exercise commonly referred to as the latihan kejiwaan, which was said by Muhammad Subuh to be guidance from "the Power of God" or "the Great Life Force".

[106][107] Muhammad Subuh saw the present age as one that demands personal evidence and proof of religious or spiritual realities, as people no longer just believe in words.

[112] Since 2003, "Shaar Hashamayim" synagogue (unaffiliated) has been serving the local Jewish community of some 20 people in Tondano city, North Sulawesi, which is attended by around 8 Orthodox Jews.

The ordination took place at The Actors' Temple, officially named Congregation Ezrath Israel, is a non-denominational Jewish synagogue located at 339 West 47th Street, Manhattan New York, July 2, 2015.

[128][129] In 2012, civil servant Alexander Aan was sentenced to 30 months in prison for writing "God doesn't exist" on his Facebook page and sharing explicit material about the prophet Muhammad online,[130][131] sparking nationwide debate.

The meeting, attended by ASEAN countries, Australia, East Timor, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea was intended to discuss possible cooperation between different religious groups to minimise inter-religious conflict in Indonesia.

In 2016, at a campaign stop during the capital city's gubernatorial election, Ahok stated some citizens would not vote for him because they were being "threatened and deceived" by those using the verse Al-Ma'ida 51 of the Qur'an and variations of it.

[141] Subsequent government attempts, particularly by the country's intelligence agency (BIN), in curbing radicalism has been called an attack on Islam by some sectarian figures.

In 2022, based on civil registration data from Ministry of Home Affairs, 87.02% of Indonesians are Muslims, 10.49% Christians (7.43% Protestants, 3.06% Roman Catholic), 1.69% Hindu, 0.73% Buddhists, 0.03% Confucians and 0.04% others.