History of television

[12][13] It also interested Deputy Consul General Carl Raymond Loop who filled a US consular report from London containing considerable detail about Low's system.

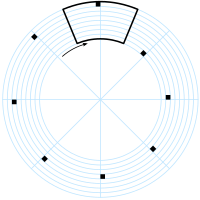

[14][15] Low's invention employed a matrix detector (camera) and a mosaic screen (receiver/viewer) with an electro-mechanical scanning mechanism that moved a rotating roller over the cell contacts providing a multiplex signal to the camera/viewer data link.

The cost of the apparatus is considerable because the conductive sections of the roller are made of platinum..." In 1914, the demonstrations certainly garnered a lot of media interest, with The Times reporting on 30 May: An inventor, Dr. A. M. Low, has discovered a means of transmitting visual images by wire.

[21] On December 25, 1926, Kenjiro Takayanagi demonstrated a television system with a 40-line resolution that employed a Nipkow disk scanner and CRT display at Hamamatsu Industrial High School in Japan.

[22] On April 7, 1927, a team from Bell Telephone Laboratories demonstrated television transmission from Washington, D.C. to New York City, using a prototype array of 50 lines containing 50 individual neon lights each against a gold-appearing background, as a display to make the images visible to an audience.

[35] A cathode ray tube was successfully demonstrated as a displaying device by the German Professor Max Dieckmann in 1906, his experimental results were published by the journal Scientific American in 1909.

[74][75] Philo Farnsworth gave the world's first public demonstration of an all-electronic television system, using a live camera, at the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia on August 25, 1934, and for ten days afterwards.

[76][77] In Britain the EMI engineering team led by Isaac Shoenberg applied in 1932 for a patent for a new device they dubbed "the Emitron",[78][79] which formed the heart of the cameras they designed for the BBC.

In November 1936, a 405-line broadcasting service employing the Emitron began at studios in Alexandra Palace and transmitted from a specially built mast atop one of the Victorian building's towers.

[80] The original American iconoscope was noisy, had a high ratio of interference to signal, and ultimately gave disappointing results, especially when compared to the high-definition mechanical scanning systems then becoming available.

[93][97] American television broadcasting at the time consisted of a variety of markets in a wide range of sizes, each competing for programming and dominance with separate technology, until deals were made and standards agreed upon in 1941.

[108] Polish inventor Jan Szczepanik patented a color television system in 1897, using a selenium photoelectric cell at the transmitter and an electromagnet controlling an oscillating mirror and a moving prism at the receiver.

[115] His system incorporated synchronized, two color, red and blue-green, rotating filters, placed in front of both the camera, and CRT, to add false colour to the monochromatic television broadcasts.

One of the great technical challenges of introducing color broadcast television was the desire to conserve bandwidth, potentially three times that of the existing black-and-white standards, and not use an excessive amount of radio spectrum.

However, due to the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia and the following normalization period, the broadcaster was ultimately forced to adopt the SECAM color system used by the rest of the Eastern Bloc.

In December 1932, Barthélemy carried out an experimental program in black and white (definition: 60 lines) one hour per week, "Paris Télévision", which gradually became daily from early 1933.

These German-controlled television broadcasts from the Eiffel Tower in Paris were able to be received on the south coast of England by Royal Air Force and BBC engineers,[146] who photographed the station identification image direct from the screen.

During this time, Southampton earned the distinction of broadcasting the first-ever live television interview, which featured Peggy O'Neil, an actress and singer from Buffalo, New York.

The outbreak of the Second World War caused the BBC service to be abruptly suspended on September 1, 1939, at 12:35 pm, after a Mickey Mouse cartoon and test signals were broadcast,[162] so that transmissions could not be used as a beacon to guide enemy aircraft to London.

Thousands waited to catch a glimpse of the Broadway stars who appeared on the 6 in (150 mm) square image, in an evening event to publicize a weekday programming schedule offering films and live entertainers during the four-hour daily broadcasts.

Appearing were boxer Primo Carnera, actors Gertrude Lawrence, Louis Calhern, Frances Upton and Lionel Atwill, WHN announcer Nils Granlund, the Forman Sisters, and a host of others.

On June 15, 1936, Don Lee Broadcasting began a one-month-long demonstration of high definition (240+ line) television in Los Angeles on W6XAO (later KTSL, now KCBS-TV) with a 300-line image from motion picture film.

[175] By June 1939, regularly scheduled 441-line electronic television broadcasts were available in New York City and Los Angeles, and by November on General Electric's station in Schenectady.

[181] The FCC adopted NTSC television engineering standards on May 2, 1941, calling for 525 lines of vertical resolution, 30 frames per second with interlaced scanning, 60 fields per second, and sound carried by frequency modulation.

The first official, paid advertising to appear on American commercial television occurred on the afternoon of July 1, 1941, over New York station WNBT (now WNBC) before a baseball game between the Brooklyn Dodgers and Philadelphia Phillies.

[184] On the few that remained, programs included entertainment such as boxing and plays, events at Madison Square Garden, and illustrated war news as well as training for air raid wardens and first aid providers.

[190] In 1945 British science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke proposed a worldwide communications system that would function by means of three satellites equally spaced apart in earth orbit.

The transmissions were focused on the Indian subcontinent but experimenters were able to receive the signal in Western Europe using home-constructed equipment that drew on UHF television design techniques already in use.

Stationary and mobile downlink stations with parabolic antennas 13.1 and 8.2 feet (4 and 2.5 m)[204] in diameter were receiving signal from Gorizont communication satellites deployed to geostationary orbits.

[215] The satellite television dishes of the systems in the late 1970s and early 1980s were 10 to 16 feet (3.0 to 4.9 m) in diameter,[216] made of fibreglass or solid aluminum or steel,[217] and in the United States cost more than $5,000, sometimes as much as $10,000.