History of the Cyclades

The best-known are, from north to south and from east to west: Andros, Tinos, Mykonos, Naxos, Amorgos, Syros, Paros and Antiparos, Ios, Santorini, Anafi, Kea, Kythnos, Serifos, Sifnos, Folegandros and Sikinos, Milos and Kimolos; to these can be added the little Cyclades: Irakleia, Schoinoussa, Koufonisi, Keros and Donoussa, as well as Makronisos between Kea and Attica, Gyaros, which lies before Andros, and Polyaigos to the east of Kimolos and Thirassia, before Santorini.

[12] Three great periods have traditionally been designated (equivalent to those that divide the Helladic on the continent and the Minoan in Crete):[13] The study of skeletons found in tombs, always in cists, shows an evolution from the Neolithic.

[14] The sexual division of labour remained the same as that identified for the Early Neolithic: women busied themselves with small domestic and agricultural tasks, while men took care of larger duties and crafts.

The oldest bronze containing tin was found at Kastri on Tinos (dating to the time of the Phylakopi Culture) and their composition proves they came from Troad, either as raw materials or as finished products.

One group in the north around Kea and Syros tended to approach the Northeast Aegean from a cultural point of view, while the Southern Cyclades seem to have been closer to the Cretan civilisation.

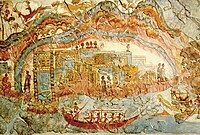

[25] For a time it was proposed that the great buildings at Akrotiri on Santorini (the West House) or at Phylakopi might be the palaces of foreign governors, but no formal proof exists that could back up this hypothesis.

From the beginning of excavations in 1967, the Greek archaeologist Spiridon Marinatos noted that the city had undergone a first destruction, due to an earthquake, before the eruption, as some of the buried objects were ruins, whereas a volcano alone may have left them intact.

[32] During the time of troubles accompanied by destruction that the continental kingdoms experienced (Late Helladic III B), relations cooled, going so far as to stop (as indicated by the disappearance of Mycenaean objects from the corresponding strata on the islands).

[32] Relations were resumed during Late Helladic III C. To the importation of objects (jars with handles decorated with squids) was also added the movement of peoples with migrations coming from the continent.

[38] From the 8th century BC, the Cyclades experienced an apogee linked in great part to their natural riches (obsidian from Milos and Sifnos, silver from Syros, pumice stone from Santorini and marble, chiefly from Paros).

[39] Cycladic cities celebrated their prosperity through great sanctuaries: the treasury of Sifnos, the Naxian column at Delphi or the terrace of lions offered by Naxos to Delos.

[41] In 479 BC, certain Cycladic cities (on Kea, Milos, Tinos, Naxos and Kythnos) were present beside other Greeks at the Battle of Plataea, as attested by the pedestal of the statue consecrated to Zeus the Olympian, described by Pausanias.

[45] Thus the Cyclades entered the “district” of the islands (along with Imbros, Lesbos and Skyros) and no longer contributed to the League except through installments of silver, the amount of which was set by the Athenian Assembly.

[53] Philip V of Macedon, after the Second Punic War, turned his attention to the Cyclades, which he ordered the Aetolian pirate Dicearchus to ravage[59] before taking control and installing garrisons on Andros, Paros and Kythnos.

The catacombs at Trypiti on Milos, unique in the Aegean and in Greece, of very simple workmanship, as well as the very close baptismal fonts, confirms that a Christian community existed on the island at least from the 3rd or 4th century.

During the rule of Justinian I, the Cyclades, Cyprus and Caria, together with Moesia Secunda (present-day northern Bulgaria) and Scythia Minor (Dobruja), were brought together under the authority of the quaestura exercitus set up at Odessus (now Varna).

[84] The Saracen pirates of Crete, having taken it during a raid on Lesbos in 837, would stop at Paros on the return journey and there attempt to pillage the church of Panaghia Ekatontopiliani; Nicetas, in the service of Leo VI the Wise, recorded the damages.

[98] In effect, the decline of the Seljuks left the field open in Asia Minor to a certain number of Turkmen principalities, those of which were closest to the sea began launching raids on the archipelago from 1330 in which the islands were regularly pillaged and their inhabitants taken into slavery.

[100] Moreover, in the 1560s, the coalition between the Pope, the Venetians and the Spaniards (the future Holy League that would triumph at Lepanto) was being put in place, and the Latin seigneurs of the Cyclades were being sought out and seemed ready to join the effort (financially and militarily).

At the end of the 17th century, the islands where they wintered made a living only due to their presence: Milos, Mykonos and above all Kimolos,[112] which owed its Latin name, Argentieri, as much to the colour of its beaches or its mythical silver mines as to the amounts spent by the pirates.

When the Ottoman navy managed to break the Venetian blockade and the Westerners were forced to retreat, the latter ravaged the islands; forests and olive groves were destroyed and all livestock was stolen.

[102] Tournefort, visiting the Cyclades in 1701, counted up these Orthodox monasteries: thirteen on Milos, six on Sifnos, at least one on Serifos, sixteen on Paros, at least seven on Naxos, one on Amorgos, several on Mykonos, five on Kea and at least three on Andros (information is missing for the remaining islands).

[120] Indeed, the Catholic Church showed itself to be very active in the islands during the 17th century, taking advantage of the fact that it was under the protection of the French and Venetian ambassadors at Constantinople, and of the wars between Venice and the Ottoman Empire, which weakened the Turks’ position in the archipelago.

[115] When North Africa had been definitively integrated into the Ottoman Empire, and above all when the Cyclades passed to the Kapudan Pasha, there was no longer any question of the Barbary pirates continuing their raids there.

[124] Likewise, the marquis de Fleury, considered a pirate, came to settle in the Cyclades with financial backing from the Marseille Chamber of Commerce at a moment when the renewal of the capitulations was being negotiated.

Russia, which was seeking a warm-water port, regularly confronted the Ottoman Empire in its attempt to access the Black Sea and through it the Mediterranean; it knew how to put these Greek legends to good use.

The inhabitants of Anafi left in such great numbers for Athens during and after Otto's reign that the neighbourhood they built, in their traditional architecture, at the foot of the Acropolis still bears the name of Anafiotika.

The failure of the Cretan insurrection of 1866-67 brought numerous refugees to Milos, who moved, like the Peloponnesians on Syros a few years earlier, onto the coast and there created, at the foot of the old medieval village of the Frank seigneurs, a new port, that of Adamas.

[158] Andros was one of the rare shipowners’ islands that managed to operate steam engines (for example, the source of the Goulandris’ fortune) and until the 1960s-1970s, it supplied the Hellenic Navy with numerous sailors.

This is less true for small, infertile rocks like Anafi[178] or Donoussa, which numbers (2001) 120 inhabitants and six pupils in its primary school but 120 rooms for rent, two travel agencies and a bakery open only during summer.