History of Greek

Although it split off from other Indo-European languages around the 3rd millennium BCE (or possibly before), it is first attested in the Bronze Age as Mycenaean Greek.

For much of the period of Modern Greek, the language existed in a situation of diglossia, where speakers would switch between informal varieties known as Dimotiki and a formal one known as Katharevousa.

Since the decipherment of Linear B, searches were made "for earlier breaks in the continuity of the material record that might represent the 'coming of the Greeks'".

[2] However, the latter estimate, accepted by the majority of scholars,[3] was criticized by John E. Coleman as being based on stratigraphic discontinuities at Lerna that other archaeological excavations in Greece demonstrated were the product of chronological gaps or separate deposit-sequencing instead of cultural changes.

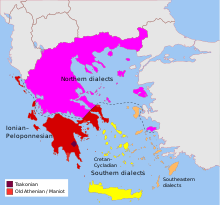

[5] Ivo Hajnal dates the beginning of the diversification of Proto-Greek into the subsequent Greek dialects to a point not significantly earlier than 1700 BC.

After the fall of the Mycenaean civilization during the Bronze Age collapse, there was a period of about five hundred years when writing was either not used or nothing has survived to the present day.

As Greek culture under Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) and his successors spread from Asia Minor to Egypt and the border regions of India the Attic dialect became the basis of the Koiné (Κοινή; "common").

The beginning of Medieval Greek is occasionally dated back to as early as the 4th century, either to 330, when the political centre of the monarchy was moved to Constantinople, or to 395, the division of the Empire.

It is only after the Eastern Roman-Byzantine culture was subjected to such massive change in the 7th century that a turning point in language development can be assumed.

Greek is spoken today by approximately 12–15 million people, mainly in Greece and Cyprus, but also by minority and immigrant communities in many other countries.