History of the telephone

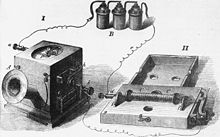

Before the invention of electromagnetic telephones, mechanical acoustic devices existed for transmitting speech and music over a greater distance.

The classic example is the children's toy made by connecting the bottoms of two paper cups, metal cans, or plastic bottles with tautly held string.

The gourd and stretched-hide version resides in the Smithsonian Museum collection and dates back to around the 7th century AD.

[9] The electrical telegraph was first commercialized by Sir William Fothergill Cooke and entered use on the Great Western Railway in England.

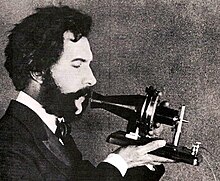

Antonio Meucci, Philipp Reis, Alexander Graham Bell, and Elisha Gray amongst others, have all been credited with the telephone's invention.

[12] The Italian inventor and businessman Antonio Meucci has been recognized by the U.S. House of Representatives for his contributory work on the telephone.

Either manually by operators, or automatically by machine switching equipment, it interconnects individual subscriber lines for calls made between them.

These made telephones an available and comfortable communication tool for many purposes, and it gave the impetus for the creation of a new industrial sector.

On 3 November 1877, Coy applied for and received a franchise from the Bell Telephone Company for New Haven and Middlesex Counties.

Coy, along with Herrick P. Frost and Walter Lewis, who provided the capital, established the District Telephone Company of New Haven on 15 January 1878.

[21] The switchboard built by Coy was, according to one source, constructed of "carriage bolts, handles from teapot lids and bustle wire."

Such sound-powered telephones survived in small numbers through the 20th century in military and maritime applications where the ability to create its own electrical power was crucial.

The Edison patents kept the Bell monopoly viable into the 20th century, by which time telephone networks were more important than the instrument.

Western Union, already using telegraph exchanges, quickly extended the principle to its telephones in New York City and San Francisco, and Bell was not slow in appreciating the potential.

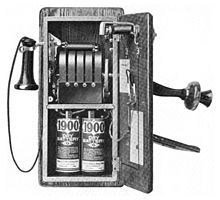

Telephones connected to the earliest Strowger automatic exchanges had seven wires, one for the knife switch, one for each telegraph key, one for the bell, one for the push button and two for speaking.

After protracted patent litigation, a federal court ruled in 1892 that Edison and not Emile Berliner was the inventor of the carbon microphone.

Disadvantages of single-wire operation, such as crosstalk and hum from nearby AC power wires, had already led to the use of twisted pairs and, for long-distance telephones, four-wire circuits.

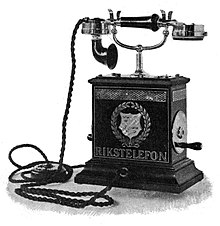

Since Stockholm consists of islands, telephone service offered relatively large advantages, but had to use submarine cables extensively.

By 1904, over three million phones were connected by manual switchboard exchanges in the U.S.[33] By 1914, the U.S. was the world leader in telephone density and had more than twice the teledensity of Sweden, New Zealand, Switzerland, and Norway.

The circuit diagram[35] of the model 102 shows the direct connection of the receiver to the line, while the transmitter was induction coupled, with energy supplied by a local battery.

Starting in the 1930s, the base of the telephone also enclosed its bell and induction coil, obviating the need for a separate ringer box.

The history of mobile phones can be traced back to two-way radios permanently installed in vehicles such as taxicabs, police cruisers, railroad trains, and the like.

In December 1947, Bell Labs engineers Douglas H. Ring and W. Rae Young proposed hexagonal cell transmissions for mobile phones.

Cellular technology was undeveloped until the 1960s, when Richard H. Frenkiel and Joel S. Engel of Bell Labs developed the electronics.

On 3 April 1973, Motorola manager Martin Cooper placed a cellular-phone call (in front of reporters) to Dr. Joel S. Engel, head of research at AT&T's Bell Labs.

The rapid development and wide adoption of pulse-code modulation (PCM) digital telephony was enabled by metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) technology.

[39][41] The silicon-gate CMOS (complementary MOS) PCM codec-filter chip, developed by Hodges and W.C. Black in 1980,[39] has since been the industry standard for digital telephony.

[43][39] The British companies Pye TMC, Marconi-Elliott and GEC developed the digital push-button telephone, based on MOS IC technology, in 1970.

It used MOS IC logic, with thousands of MOSFETs on a chip, to convert the keypad input into a pulse signal.

One of its features is the touch screen that facilitates the primary interaction for users for most tasks, such as dialing telephone numbers.

Centennial Issue of 1976