Holonomy

For flat connections, the associated holonomy is a type of monodromy and is an inherently global notion.

Any kind of connection on a manifold gives rise, through its parallel transport maps, to some notion of holonomy.

Holonomy was introduced by Élie Cartan (1926) in order to study and classify symmetric spaces.

In 1952 Georges de Rham proved the de Rham decomposition theorem, a principle for splitting a Riemannian manifold into a Cartesian product of Riemannian manifolds by splitting the tangent bundle into irreducible spaces under the action of the local holonomy groups.

The decomposition and classification of Riemannian holonomy has applications to physics and to string theory.

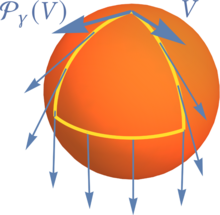

Let E be a rank-k vector bundle over a smooth manifold M, and let ∇ be a connection on E. Given a piecewise smooth loop γ : [0,1] → M based at x in M, the connection defines a parallel transport map Pγ : Ex → Ex on the fiber of E at x.

Explicitly, if γ is a path from x to y in M, then Choosing different identifications of Ex with Rk also gives conjugate subgroups.

Sometimes, particularly in general or informal discussions (such as below), one may drop reference to the basepoint, with the understanding that the definition is good up to conjugation.

Define an equivalence relation ~ on P by saying that p ~ q if they can be joined by a piecewise smooth horizontal path in P. The holonomy group of ω based at p is then defined as The restricted holonomy group based at p is the subgroup

As above, sometimes one drops reference to the basepoint of the holonomy group, with the understanding that the definition is good up to conjugation.

Then it can be shown that H(p), with the evident projection map, is a principal bundle over M with structure group

This corresponds to taking a derivative of the parallel transport maps at x = y = 0: where R is the curvature tensor.

[8] In 1955, M. Berger gave a complete classification of possible holonomy groups for simply connected, Riemannian manifolds which are irreducible (not locally a product space) and nonsymmetric (not locally a Riemannian symmetric space).

Finally one checks that the first of these two extra cases only occurs as a holonomy group for locally symmetric spaces (that are locally isomorphic to the Cayley projective plane), and the second does not occur at all as a holonomy group.

Berger's original classification also included non-positive-definite pseudo-Riemannian metric non-locally symmetric holonomy.

The last case, manifolds with holonomy contained in SO(n, H), were shown to be locally flat by R.

Finally, Berger's paper lists possible holonomy groups of manifolds with only a torsion-free affine connection; this is discussed below.

[10] Riemannian manifolds with special holonomy play an important role in string theory compactifications.

[12] This is because special holonomy manifolds admit covariantly constant (parallel) spinors and thus preserve some fraction of the original supersymmetry.

The holonomy cannot be computed exactly due to finite sampling effects, but it is possible to construct a numerical approximation using ideas from spectral graph theory similar to Vector Diffusion Maps.

The resulting algorithm, the Geometric Manifold Component Estimator (GeoManCEr) gives a numerical approximation to the de Rham decomposition that can be applied to real-world data.

The de Rham decomposition theorem does not apply to affine holonomy groups, so a complete classification is out of reach.

On the way to his classification of Riemannian holonomy groups, Berger developed two criteria that must be satisfied by the Lie algebra of the holonomy group of a torsion-free affine connection which is not locally symmetric: one of them, known as Berger's first criterion, is a consequence of the Ambrose–Singer theorem, that the curvature generates the holonomy algebra; the other, known as Berger's second criterion, comes from the requirement that the connection should not be locally symmetric.

Berger's list was later shown to be incomplete: further examples were found by R. Bryant (1991) and by Q. Chi, S. Merkulov, and L. Schwachhöfer (1996).

The search for examples ultimately led to a complete classification of irreducible affine holonomies by Merkulov and Schwachhöfer (1999), with Bryant (2000) showing that every group on their list occurs as an affine holonomy group.

The relationship is particularly clear in the case of complex affine holonomies, as demonstrated by Schwachhöfer (2001).

Using the classification of quaternion-Kähler symmetric spaces, the second family gives the following complex symplectic holonomy groups: (In the second row, ZC must be trivial unless n = 2.)

There is a similar word, "holomorphic", that was introduced by two of Cauchy's students, Briot (1817–1882) and Bouquet (1819–1895), and derives from the Greek ὅλος (holos) meaning "entire", and μορφή (morphē) meaning "form" or "appearance".

About the second part: "It is remarkably hard to find the etymology of holonomic (or holonomy) on the web.

I found the following (thanks to John Conway of Princeton): 'I believe it was first used by Poinsot in his analysis of the motion of a rigid body.