Homo antecessor

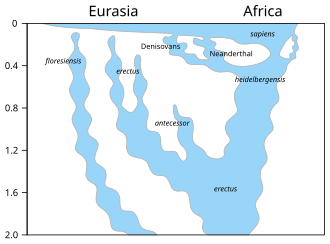

Homo antecessor (Latin "pioneer man") is an extinct species of archaic human recorded in the Spanish Sierra de Atapuerca, a productive archaeological site, from 1.2 to 0.8 million years ago during the Early Pleistocene.

The first fossils were found in the Gran Dolina cave in 1994, and the species was formally described in 1997 as the last common ancestor of modern humans and Neanderthals, supplanting the more conventional H. heidelbergensis in this position.

In 1976, Spanish palaeontologist Trinidad Torres investigated the Gran Dolina for bear fossils (he recovered Ursus remains), but was advised by the Edelweiss Speleological Club to continue at the nearby Sima de los Huesos ("bone pit").

[3] In the first field seasons from 1994–1995, the dig team excavated a small test pit (to see if the unit warranted further investigation) in the southeast section measuring 6 m2 (65 sq ft).

[6] In 2011, after providing a much more in depth analysis of the Sima del Elefante material, Castro and colleagues were unsure of the species classification, opting to leave it at Homo sp.

[7] The stone tool assemblage at the Gran Dolina is broadly similar to several other contemporary ones across Western Europe, which may represent the work of the same species, although this is unconfirmable because many of these sites have not produced human fossils.

[2] In 2014 fifty footprints dating to between 1.2 million and 800,000 years ago were discovered in Happisburgh, England, which could potentially be attributed to an H. antecessor group given it is the only human species identified during that time in Western Europe.

[13] In 2007 primatologist Esteban Sarmiento and colleagues questioned the legitimacy of H. antecessor as a separate species because much of the skull anatomy is unknown; H. heidelbergensis is known from roughly the same time and region; and because the type specimen was a child (the supposedly characteristic features could have disappeared with maturity.)

[17] In 2020 Dutch molecular palaeoanthropologist Frido Welker and colleagues concluded H. antecessor is not a modern human ancestor by analysing ancient proteins collected from the tooth ATD6-92.

Fluvially deposited fossils (dragged in by a stream of water) were also recovered from Facies A in layers TD6.2.2, TD6.2.1 and TD6.1.2, indicated by limestone gravel within the size range of the remains.

The most notable traits are a completely flat face and a curved zygomaticoalveolar crest (the bar of bone connecting the cheek to the part of the maxilla that holds the teeth).

H. antecessor suggests the modern human face evolved and disappeared multiple times in the past, which is not unlikely as facial anatomy is strongly influenced by diet and thus the environment.

[17] The upper incisors are shovel-shaped (the lingual, or tongue, side is distinctly concave), a feature characteristic of other Eurasian human populations, including modern.

[5] The shoulder blade is similar to all Homo with a typical human body plan, indicating H. antecessor was not as skilled a climber as non-human apes or pre-erectus species, but was capable of efficiently launching projectiles such as stones or spears.

The lateral facet encroaches onto a straight flat area as opposed to being limited to a defined vastus notch, an infrequent condition among any human species.

This somewhat converges with the condition exhibited in Neanderthals, which is generally explained as a response to a heavy and robust body, to alleviate the consequently higher stress to the articular cartilage in the ankle joint.

Osteophytes normally form as a response to stress due to osteoarthritis, which can result from old age or improper loading of the joint as a consequence of bone misalignment or ligament laxity.

If so, the lesion was caused by a local trauma, such as strain on the soft tissue around the joint due to high intensity activity, or a fracture of the left femur and/or tibia (that is unconfirmable since neither bone is associated with this individual).

This condition is most often encountered by soldiers, long distance runners, and potentially flatfooted people whose foot bones failed under repeated, high intensity activity.

This industry is found elsewhere in Early Pleistocene Spain—notably in Barranc de la Boella and the nearby Galería—distinguished by the preparation and sharpening of cores before flaking, the presence of (crude) bifaces, and some degree of standardisation of tool types.

In 2020 French anthropologist Marie-Hélène Moncel argued the appearance of typical Achuelean bifaces 700,000 years ago in Europe was too sudden to be the result of completely independent evolution from local technologies, so there must have been influence from Africa.

[19] In the lower part of TD6.3 (TD6 subunit 3), 84 stone tools were recovered, predominantly small, unmodified quartzite pebbles with percussive damage—probably inflicted from pounding items such as bone—as opposed to manufacturing more specialised implements.

They made use of the unipolar longitudinal method, flaking off only one side of a core, probably to compensate for the lack of preplanning, opting to knap irregularly shaped and thus poorer quality pebbles.

The Sierra de Atapuerca features an abundance and diversity of mineral outcroppings suitable for stone tool manufacturing, in addition to chert and quartz namely quartzite, sandstone, and limestone, which could all be collected within only 3 km (1.9 mi) of the Gran Dolina.

[38] In 2016, small mammal bones burned in fires exceeding 600 °C (1,112 °F) were identified from 780- to 980-thousand-year-old deposits at Cueva Negra [es] in southern Spain, which potentially could have come from a human source as such a high temperature is usually (though not always) recorded in campfires as opposed to natural bushfires.

[38] Despite glacial cycles, the climate was probably similar or a few degrees warmer compared to that of today's, with the coldest average temperature reaching 2 °C (36 °F) sometime in December and January, and the hottest in July and August 18 °C (64 °F).

[6] The Happisburgh footprints were lain in estuarine mudflats with open forests dominated by pine, spruce, birch, and in wetter areas alder, with patches of heath and grasslands; the vegetation is consistent with the cooler beginning or end of an interglacial.

[8] H. antecessor probably migrated from the Mediterranean shore into inland Iberia when colder glacial periods were transitioning to warmer interglacials, and warm grasslands dominated, vacating the region at any other time.

When this is seen in prehistoric modern human specimens, it is typically interpreted as evidence of exocannibalism, a form of ritual cannibalism where one eats someone from beyond their social group, such as an enemy from a neighbouring tribe.

They consider this explanation as better fitting the demographic distribution of the eaten due to the high youth mortality rates in hunter-gatherer groups, while also granting that the high number of young individuals among the eaten may have been due to a "low-risk hunting strategy" (juveniles of foreign groups were easier to catch and kill) or a "deliberate cultural strategy aimed to defend the territory and eliminate competitors" by targeting their offspring.

Natural History Museum, London