XY sex-determination system

In one instance, a seemingly normal female with a vagina, cervix, and ovaries had XY chromosomes, however the details and mechanism behind this is unknown, and could potentially be due to chimerism.

The platypus, a monotreme, use five pairs of different XY chromosomes with six groups of male-linked genes, AMH being the master switch.

[12] Many economically important crops are known to have an XY system of sex determination, including kiwifruit,[13] asparagus,[14] grapes[15] and date palms.

Now in 1959 when the karyotype of Klinefelter [a male who is XXY] and Turner [a female who has one X] syndromes was discovered, it became clear that in humans it was the presence or the absence of the Y chromosome that's sex determining.

There are a number of factors that are there, like WNT4, like DAX1, whose function is to counterbalance the male pathway.In mammals, including humans, the SRY gene triggers the development of non-differentiated gonads into testes rather than ovaries.

A recent finding suggests that ovary development and maintenance is an active process,[22] regulated by the expression of a "pro-female" gene, FOXL2.

In an interview[23] for the TimesOnline edition, study co-author Robin Lovell-Badge explained the significance of the discovery: We take it for granted that we maintain the sex we are born with, including whether we have testes or ovaries.

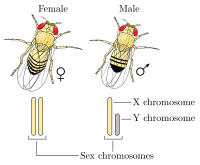

Scientists have been studying different sex determination systems in fruit flies and animal models to attempt an understanding of how the genetics of sexual differentiation can influence biological processes like reproduction, ageing[24] and disease.

Human ova, like those of other mammals, are covered with a thick translucent layer called the zona pellucida, which the sperm must penetrate to fertilize the egg.

[26] Recent research indicates that human ova may produce a chemical which appears to attract sperm and influence their swimming motion.

[27] Maternal influences may also be possible that affect sex determination in such a way as to produce fraternal twins equally weighted between one male and one female.

[28] The time at which insemination occurs during the estrus cycle has been found to affect the sex ratio of the offspring of humans, cattle, hamsters, and other mammals.

[25] Hormonal and pH conditions within the female reproductive tract vary with time, and this affects the sex ratio of the sperm that reach the egg.

[33] The first clues to the existence of a factor that determines the development of testis in mammals came from experiments carried out by Alfred Jost,[34] who castrated embryonic rabbits in utero and noticed that they all acquired a female phenotype.

[35] In 1959, C. E. Ford and his team, in the wake of Jost's experiments, discovered[36] that the Y chromosome was needed for a fetus to develop as male when they examined patients with Turner's syndrome, who grew up as phenotypic females, and found them to be X0 (hemizygous for X and no Y).

At the same time, Jacob & Strong described a case of a patient with Klinefelter syndrome (XXY),[37] which implicated the presence of a Y chromosome in development of maleness.

[38] All these observations led to a consensus that a dominant gene that determines testis development (TDF) must exist on the human Y chromosome.