Horatio Seymour

He defeated Hunt in the 1852 gubernatorial election, and spent much of his tenure trying to reunify the fractured Democratic Party, losing his 1854 re-election campaign in part due to this disunity.

Seymour never again sought public office but remained active in politics and supported Grover Cleveland's 1884 campaign for president.

Though admitted to the bar in 1832, he did not enjoy work as an attorney and was primarily preoccupied with politics and managing his family's business interests.

[5] Seymour's first role in politics came in 1833, when he was named military secretary to the state's newly elected Democratic governor, William L. Marcy with the rank of colonel.

[3] The six years in that position gave Seymour an invaluable education in the politics of the state, and established a firm friendship between the two men.

Seymour and the Softs supported the candidacy of their leader, Marcy, for the presidency in 1852, but when he was defeated they enthusiastically campaigned for Franklin Pierce in 1852.

That year proved a good one for the Softs, as Seymour, again supported by a unified Democratic Party, narrowly defeated Hunt in a gubernatorial rematch, while Pierce, overwhelmingly elected president, appointed Marcy as his Secretary of State.

Whigs controlling the state legislature also sought to injure him further politically by responding to his call for action on the problem of alcohol abuse with a bill establishing a statewide prohibition, which Seymour vetoed as unconstitutional.

Despite his defeat, as a former governor of the largest state of the Union, Seymour emerged as a prominent figure in party politics at the national level.

In 1856, he was considered a possible compromise presidential candidate in the event of a deadlock between Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan until he wrote a letter definitively ruling himself out.

Though Seymour accepted the nomination with reluctance, he threw himself into the election, campaigning across the state in the hope that a Democratic victory would restrain the actions of the Radical Republicans in Washington.

He won a close race against the Republican candidate James S. Wadsworth, one of a series of victories by the Democratic ticket in the state that year.

He opposed the Lincoln administration's institution of the military draft in 1863 on constitutional grounds, an act which led many to question his support for the war.

While not opposed to the goal he preferred to establish voting provisions through a constitutional amendment that was working its way simultaneously through the state legislature; nonetheless, his veto was portrayed by opponents as hostility to the soldiers.

His decision to pay the state's foreign creditors using gold rather than greenbacks alienated "easy money" supporters, while his veto of a bill granting traction rights on Broadway in Manhattan earned him the opposition of Tammany Hall.

Finally, his efforts to conciliate the rioters during the New York Draft Riots of July 1863 was used against him by the Republicans, who accused him of treason and support for the Confederacy.

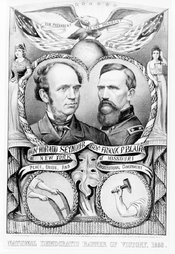

Of the numerous candidates in contention, George H. Pendleton, who had run as the Democratic vice-presidential nominee in 1864, enjoyed considerable support but alienated the fiscal conservatives in the party with his plan to pay off federal debt using greenbacks.

He faced considerable challenges; his opponent, General Ulysses S. Grant, enjoyed the support of a unified Republican party and most of the nation's press.

While he generally adhered to the tradition that presidential nominees did not actively campaign, Seymour did undertake a tour of the Midwest and the mid-Atlantic states in mid-October.

[6] The Republican campaign, by contrast, was the first in which they "waved the bloody shirt", highlighting Seymour's support for mob violence against African-Americans.