Henry Wilson

Henry Wilson (born Jeremiah Jones Colbath; February 16, 1812 – November 22, 1875) was the 18th vice president of the United States, serving from 1873 until his death in 1875, and a senator from Massachusetts from 1855 to 1873.

[2] Winthrop Colbath was a militia veteran of the War of 1812[3] who worked as a day laborer and hired himself out to local farms and businesses, in addition to occasionally running a sawmill.

[15] Wilson learned the trade in a few weeks, bought out his employment contract for fifteen dollars, and opened his own shop, intending to save enough money to study law.

[5] Wilson resolved to dedicate himself "to the cause of emancipation in America,"[5] and after regaining his health returned to New England, where he furthered his education by attending several New Hampshire academies, including schools in Strafford, Wolfeboro, and Concord.

[23] As a result of this effort, in late 1845 Wilson and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier were chosen to submit in person a petition to Congress containing the signatures of 65,000 Massachusetts residents opposed to Texas annexation.

[5] Wilson was a delegate to the 1848 Whig National Convention, but left the party after it nominated slave owner Zachary Taylor for president and took no position on the Wilmot Proviso, which would have prohibited slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War.

[24] Wilson and Charles Allen, another Massachusetts delegate, withdrew from the convention, and called for a new meeting of anti-slavery advocates in Buffalo, which launched the Free Soil Party.

In addition to undertaking legislative efforts to provide uniforms and other equipment, in 1843 Wilson joined the militia himself, becoming a major in the 1st Artillery Regiment, which he later commanded with the rank of colonel.

[31] In 1855 Wilson was elected to the United States Senate by a coalition of Free-Soilers, Know Nothings, and anti-slavery Democrats, filling the vacancy caused by the resignation of Edward Everett.

This phrase came to describe the period when activists and politicians moved past the debate of anti-slavery and pro-slavery speeches and non-violent actions, and into the realm of physical violence, which in part hastened the onset of the American Civil War.

They were mustered in as the 22nd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, which he commanded as a colonel from September 27 to October 29, an honor sometimes accorded to the individual responsible for raising and equipping a regiment.

[39] Winfield Scott, the Commanding General of the United States Army since 1841, said that during the session of Congress that ended in the Spring of 1861 Wilson had done more work "than all the chairmen of the military committees had done for the last 20 years.

"[39] In July 1861, Wilson was present for the Civil War's first major battle at Bull Run Creek in Manassas, Virginia, an event which many senators, representatives, newspaper reporters, and Washington society elite traveled from the city to observe in anticipation of a quick Union victory.

"[64] On June 15, 1864, Wilson succeeded in adding a provision to an appropriations bill which addressed the pay disparity between whites and blacks in the military by authorizing equal salaries and benefits for African American soldiers.

[65] Wilson's provision stated that "all persons of color who had been or might be mustered into the military service should receive the same uniform, clothing, rations, medical and hospital attendance, and pay" as white soldiers, to date from January 1864.

The establishment of the Permanent Commission prompted Davis to suggest that "the whole plan, so long entertained, of the Academy could be successfully carried out if an act of incorporation were boldly asked for in the name of some of the leading men of science, from different parts of the country.

[39] On December 21, 1865, two days after the announcement that the states had ratified the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery, Wilson introduced a bill to protect the civil rights of African Americans.

[74] Taking the lead on this issue, Wilson urged immediate action, saying that the new state government was constitutional, and was composed of loyal Southerners, African Americans who were formerly enslaved, and Northerners who had moved south.

President Ulysses S. Grant, who succeeded Johnson in 1869, was more supportive of Congressional Reconstruction, and the remaining former Confederate states that had not rejoined the Union were readmitted during his first term.

[79] The Liberal Republican convention, held in Cincinnati in April, and headed by Carl Schurz, desired to replace Grant because of corruption in his administration, end Reconstruction, and return Southern state governments to white rule.

[83] Wilson was popular among Republicans for the vice presidential nomination, with an appealing rags-to-riches story that included his rise from indentured servant to owner and operator of a successful shoe making business.

[89][90] After denying to a reporter just a month before the election that he had a Crédit Mobilier connection, Wilson admitted involvement when he gave testimony before a Senate committee on February 13, 1873.

[95] The Senate accepted Wilson's explanation, and took no action against him, but his reputation for integrity was somewhat damaged because of his initial denial and later admission, though not sufficiently enough to prevent him from becoming vice president the following month.

[39] During periods when he was not ill, Wilson was also able to resume some of his ceremonial duties, including participating in a White House party for the King of Hawaii, David Kalākaua, in December 1874.

[103] When Free Soil and abolitionist colleague Gerrit Smith died in New York City on December 28, 1874, Wilson traveled there to view the body and take part in funeral services.

[105] The subsequent funeral arrangements included military escorts as Wilson's remains were transferred from one train station to another en route from Washington to Natick, as well as nights lying in state.

[110] According to historian George H. Haynes, during his nearly thirty years of public service Wilson practiced principled politics by championing unpopular causes, sometimes at the expense of his personal ambition.

[39] On the other hand, he was admired by fellow abolitionists for his lifelong dedication to the cause, and workingmen found inspiration in his career, since he had himself risen from a manual laborer's background.

[54] These efforts were credited with helping Wilson build coalitions, win elections, make political allies, and determine the best time to act in the Senate on issues of importance.

[117] During the Civil War, the younger Wilson attended the United States Naval Academy, but left before graduating in order to accept a commission in the Union Army.

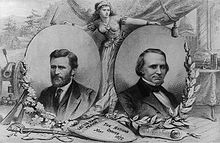

March 4, 1873

Onthank portrait, 1875