Horemheb

Horemheb, also spelled Horemhab, Haremheb or Haremhab (Ancient Egyptian: ḥr-m-ḥb, meaning "Horus is in Jubilation"),[1] was the last pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt (1550–1292 BC).

[3] He had no relation to the preceding royal family other than by marriage to Mutnedjmet, who is thought (though disputed) to have been the daughter of his predecessor, Ay; he is believed to have been of common birth.

According to the French Egyptologist Nicolas Grimal, Horemheb does not appear to be the same person as Paatenemheb (Aten Is Present In Jubilation), who was the commander-in-chief of Akhenaten's army.

[6] Grimal notes that Horemheb's political career began under Tutankhamun where he "is depicted at this king's side in his own tomb chapel at Memphis.

"[7]: 242 In the earliest known stage of his life Horemheb served as "the royal spokesman for [Egypt's] foreign affairs" and personally led a diplomatic mission to visit the Nubian governors.

[7]: 242 This resulted in a reciprocal visit by "the Prince of Miam (Aniba)" to Tutankhamun's court, "an event [that is] depicted in the tomb of the Viceroy Huy.

"[8] When Tutankhamun died while a teenager, Horemheb had already been officially designated as the rpat or iry-pat (basically the hereditary or crown prince) and idnw (deputy of the king in the entire land) by the child pharaoh; these titles are found inscribed in Horemheb's then private Memphite tomb at Saqqara, which dates to the reign of Tutankhamun since the child king's ... cartouches, although later usurped by Horemheb as king, have been found on a block which adjoins the famous gold of honour scene, a large portion of which is in Leiden.

When used alone, the Egyptologist Alan Gardiner has shown that the iry-pat title contains features of ancient descent and lawful inheritance which is identical to the designation for a "Crown Prince.

The Dutch Egyptologist Jacobus Van Dijk observes: There is no indication that Horemheb always intended to succeed Tut'ankhamun; obviously not even he could possibly have predicted that the king would die without issue.

It must always have been understood that his appointment as crown prince would end as soon as the king produced an heir, and that he would succeed Tut'ankhamun only in the eventuality of an early and / or childless death of the sovereign.

40–41 Nozomu Kawai, however, rejects Van Dijk's interpretation that Tutankhamun had nominated Horemheb as his successor and reasons that: While no objects belonging to Horemheb were found in Tutankhamun's tomb, and items among the tomb goods donated by other high-ranking officials, such as Maya and General Nakhtmin, were identified by Egyptologists.

Occasionally called The Great Edict of Horemheb,[17] it is a copy of the actual text of the king's decree to re-establish order to the Two Lands and curb abuses of state authority.

The stela's creation and prominent location emphasizes the great importance which Horemheb placed upon domestic reform.

They had no surviving children, although examinations of Mutnedjmet's mummy show that she gave birth several times, and she was buried with an infant, suggesting that she and her last child died in childbirth.

Martin and Jacobus Van Dijk in 2006 and 2007, uncovered a large hoard of 168 inscribed wine sherds and dockets, below densely compacted debris in a great shaft (called Well Room E) in KV 57.

It was disputed whether this was a contemporary text or a reference to a festival commemorating Horemheb's accession written in the reign of a later king.

However, the length of Ay's reign is not actually known and Wolfgang Helck argues that there was no standard Egyptian practice of including the years of all the rulers between Amenhotep III and Horemheb.

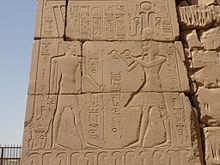

[2] Horemheb appear in reliefs wearing the typical pleated linen robe of a high ranking official depicted sitting in front of an offering table, as a pharaoh holding the pole and the sekhem sceptre of a high official (the uraeus was added after his ascension to the throne), with a benu-bird regarded as the protector of the dead as the soul of Ra sitting on a stand, and finally a man worshipping a benu-bird.

[2] The coronation inscription on the back of a double statue, showing Horemheb with his wife, tells that he is under the protection of Horus and appointed by Amun.

Under Horemheb, Egypt's power and confidence were once again restored after the internal chaos of the Amarna Period; this situation set the stage for the rise of the 19th Dynasty under such ambitious Pharaohs as Seti I and Ramesses II.

He notes that "a fragment of an alabaster vase inscribed with a funerary text for the chantress of Amun and King's Wife, Mutnodjmet, as well as pieces of a statuette of her [was found here] ...

This is similar to how Horemheb left the name of Tutankhamun on the veil of Amun bark at Karnak temple untouched.

[33] Directly after his accession to the throne, Horemheb had a tomb built in the Valley of Kings, abandoning his earlier one near Memphis.