Galerius

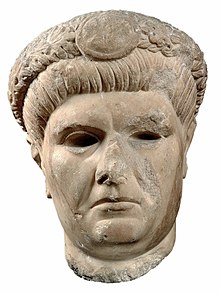

Galerius was born in the Danube provinces, either near Serdica[13] or at the place where he later built his palace named after his mother – Felix Romuliana (Gamzigrad).

[21][22]: 69 In early 294, Narseh sent Diocletian the customary package of gifts, but within Persia, he was destroying every trace of his immediate predecessors, erasing their names from public monuments.

Narseh then moved south into Roman Mesopotamia, where he inflicted a severe defeat on Galerius, then commander of the eastern forces, in the region between Carrhae (Harran, Turkey) and Callinicum (Raqqa, Syria).

In Antioch, Diocletian forced Galerius to walk a mile in advance of his imperial cart while still clad in the purple robes of an emperor.

[29] Another scholar, Roger Rees, suggests that Galerius' position at the head of the caravan was merely the conventional organization of an imperial progression, designed to show a Caesar's deference to his Augustus.

[33] Narseh retreated to Armenia to fight Galerius' force, putting himself at a disadvantage; the rugged Armenian terrain was favorable to Roman infantry, but not to Sassanid cavalry.

[29][32] Narseh's wife would live out the remainder of the war in Daphne, a suburb of Antioch, serving as a constant reminder to the Persians of the Roman victory.

[29] Galerius advanced into Media and Adiabene, winning continuous victories, most prominently near Theodosiopolis (Erzurum),[31] and securing Nisibis (Nusaybin) before 1 October 298.

These regions included the passage of the Tigris through the Anti-Taurus range; the Bitlis pass, the quickest southerly route into Persian Armenia; and access to the Tur Abdin plateau.

[36] Under the terms of the peace, Tiridates would regain both his throne and the entirety of his ancestral claim, and Rome would secure a wide zone of cultural influence in the region.

[32] Because the empire was able to sustain such constant warfare on so many fronts, it has been taken as a sign of the essential efficacy of the Diocletianic system and the goodwill of the army towards the tetrarchic enterprise.

Officially Severus reported to the western emperor, but he was absolutely devoted to the commands of his benefactor Galerius, whose power was thus established over three-quarters of the empire.

[39][40][41][42] Calmer consideration made him reluctant to open a civil war: Constantine had the devotion of Constantius' legions, and the young man's character had impressed Galerius during an encounter at Nicomedia.

[38] Galerius decided on a compromise position, allowing Constantine to rule the provinces beyond the Alps but giving him only the title of Caesar and the fourth rank among the Tetrarchs.

[43] A need for additional revenue had caused Galerius to disregard Italy's traditional exemption from any form of taxation, and Maxentius exploited local indignation to declare himself emperor.

An army led by Severus hastened to Rome, hoping to catch the usurper by surprise,[38] but Maximian, who had previously commanded many of the invading troops, came out of retirement in support of his son.

Leaving his long-time friend and military companion Licinius to guard the Danube, Galerius personally invaded Italy with a powerful army collected from Illyricum and the East.

The strength of the enemy's position made Galerius send peace overtures to Rome, professing his fatherly affection for Maxentius and promising to be generous if the rebels cooperated.

Diocletian was not anti-Christian during the first part of his reign, and historians have claimed that Galerius decided to prod him into persecuting them by secretly burning the Imperial Palace and blaming it on Christian saboteurs.