Hubble's law

In 1927, Georges Lemaître concluded that the universe might be expanding by noting the proportionality of the recessional velocity of distant bodies to their respective distances.

[16] Hubble's law is considered the first observational basis for the expansion of the universe, and is one of the pieces of evidence most often cited in support of the Big Bang model.

In this form H0 = 7%/Gyr, meaning that, at the current rate of expansion, it takes one billion years for an unbound structure to grow by 7%.

A decade before Hubble made his observations, a number of physicists and mathematicians had established a consistent theory of an expanding universe by using Einstein field equations of general relativity.

He did not grasp the cosmological implications of this fact, and indeed at the time it was highly controversial whether or not these nebulae were "island universes" outside the Milky Way galaxy.

This idea of an expanding spacetime would eventually lead to the Big Bang and Steady State theories of cosmology.

According to the Canadian astronomer Sidney van den Bergh, "the 1927 discovery of the expansion of the universe by Lemaître was published in French in a low-impact journal.

Edwin Hubble did most of his professional astronomical observing work at Mount Wilson Observatory,[27] home to the world's most powerful telescope at the time.

Though there was considerable scatter (now known to be caused by peculiar velocities—the 'Hubble flow' is used to refer to the region of space far enough out that the recession velocity is larger than local peculiar velocities), Hubble was able to plot a trend line from the 46 galaxies he studied and obtain a value for the Hubble constant of 500 (km/s)/Mpc (much higher than the currently accepted value due to errors in his distance calibrations; see cosmic distance ladder for details).

After Hubble's discovery was published, Albert Einstein abandoned his work on the cosmological constant, a term he had inserted into his equations of general relativity to coerce them into producing the static solution he previously considered the correct state of the universe.

[35] Redshift can be measured by determining the wavelength of a known transition, such as hydrogen α-lines for distant quasars, and finding the fractional shift compared to a stationary reference.

The redshift is not even directly related to the recession velocity at the time the light set out, but it does have a simple interpretation: (1 + z) is the factor by which the universe has expanded while the photon was traveling towards the observer.

However, in the standard Lambda cold dark matter model (Lambda-CDM or ΛCDM model), q will tend to −1 from above in the distant future as the cosmological constant becomes increasingly dominant over matter; this implies that H will approach from above to a constant value of ≈ 57 (km/s)/Mpc, and the scale factor of the universe will then grow exponentially in time.

Simply stated, the theorem is this: Any two points which are moving away from the origin, each along straight lines and with speed proportional to distance from the origin, will be moving away from each other with a speed proportional to their distance apart.In fact, this applies to non-Cartesian spaces as long as they are locally homogeneous and isotropic, specifically to the negatively and positively curved spaces frequently considered as cosmological models (see shape of the universe).

[44][45] Since the 17th century, astronomers and other thinkers have proposed many possible ways to resolve this paradox, but the currently accepted resolution depends in part on the Big Bang theory, and in part on the Hubble expansion: in a universe that existed for a finite amount of time, only the light of a finite number of stars has had enough time to reach us, and the paradox is resolved.

Additionally, in an expanding universe, distant objects recede from us, which causes the light emanated from them to be redshifted and diminished in brightness by the time we see it.

Occasionally a reference value other than 100 may be chosen, in which case a subscript is presented after h to avoid confusion; e.g. h70 denotes H0 = 70 h70 (km/s)/Mpc, which implies h70 = h / 0.7.

A value for q measured from standard candle observations of Type Ia supernovae, which was determined in 1998 to be negative, surprised many astronomers with the implication that the expansion of the universe is currently "accelerating"[47] (although the Hubble factor is still decreasing with time, as mentioned above in the Interpretation section; see the articles on dark energy and the ΛCDM model).

We currently appear to be approaching a period where the expansion of the universe is exponential due to the increasing dominance of vacuum energy.

Likewise, the generally accepted value of 2.27 Es−1 means that (at the current rate) the universe would grow by a factor of e2.27 in one exasecond.

[8][56] For the original 1929 estimate of the constant now bearing his name, Hubble used observations of Cepheid variable stars as "standard candles" to measure distance.

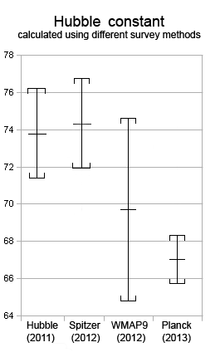

However, as techniques have improved, the estimated measurement uncertainties have shrunk, but the discrepancies have not, to the point that the disagreement is now highly statistically significant.

[56]: 2.1 As an example of the kind of work needed to reduce systematic errors, photometry on observations from the James Webb Space Telescope of extra-galactic Cepheids confirm the findings from the HST.

[74][56] The "early universe" or inverse distance ladder measures the observable consequences of spherical sound waves on primordial plasma density.

In October 2018, scientists used information from gravitational wave events (especially those involving the merger of neutron stars, like GW170817), of determining the Hubble constant.

[83] In July 2020, measurements of the cosmic background radiation by the Atacama Cosmology Telescope predict that the Universe should be expanding more slowly than is currently observed.

[84] In July 2023, an independent estimate of the Hubble constant was derived from a kilonova, the optical afterglow of a neutron star merger.

[85] Due to the blackbody nature of early kilonova spectra,[86] such systems provide strongly constraining estimators of cosmic distance.

Although intuitively appealing, this explanation requires multiple unrelated effects regardless of whether early-universe or late-universe observations are incorrect, and there are no obvious candidates.

[89] In particular, we would need to be located within a very large void, up to about a redshift of 0.5, for such an explanation to conflate with supernovae and baryon acoustic oscillation observations.

A closed universe with Ω M > 1 and Ω Λ = 0 comes to an end in a Big Crunch and is considerably younger than its Hubble age.

An open universe with Ω M ≤ 1 and Ω Λ = 0 expands forever and has an age that is closer to its Hubble age. For the accelerating universe with nonzero Ω Λ that we inhabit, the age of the universe is coincidentally very close to the Hubble age.