Huītzilōpōchtli

During their discovery and conquest of the Aztec Empire, they wrote that human sacrifice was common in worship ceremonies.

[6][7] However, Frances Karttunen points out that in Classical Nahuatl compounds are usually head final, implying that a more accurate translation may be "the left (or south) side of the hummingbird".

[9] Another origin story tells of a fierce goddess, Coatlicue, being impregnated as she was sweeping by a ball of feathers on Mount Coatepec ("Serpent Hill"; near Tula, Hidalgo).

Originally, he was of little importance to the Nahuas, but after the rise of the Aztecs, Tlacaelel reformed their religion and put Huitzilopochtli at the same level as Quetzalcoatl, Tlaloc, and Tezcatlipoca, making him a solar god.

Huitzilopochtli was said to be in a constant struggle with the darkness and required nourishment in the form of sacrifices to ensure the sun would survive the cycle of 52 years, which was the basis of many Mesoamerican myths.

Representations of Huitzilopochtli called teixiptla were also worshipped, the most significant being the one at the Templo Mayor which was made of dough mixed with sacrificial blood.

According to Aztec mythology, Huitzilopochtli needed blood as sustenance in order to continue to keep his sister and many brothers at bay as he chased them through the sky.

Its importance as the sacred center is reflected in the fact that it was enlarged frontally eleven times during the two hundred years of its existence.

16th century Dominican friar Diego Durán wrote, "These two gods were always meant to be together, since they were considered companions of equal power.

[25] This drama of sacrificial dismemberment was vividly repeated in some of the offerings found around the Coyolxauhqui stone in which the decapitated skulls of young women were placed.

[32] From a description in the Florentine Codex, Huitzilopochtli was so bright that the warrior souls had to use their shields to protect their eyes.

[33] As the precise studies of Johanna Broda have shown, the creation myth consisted of “several layers of symbolism, ranging from a purely historical explanation to one in terms of cosmovision and possible astronomical content.”[34] At one level, Huitzilopochtli's birth and victorious battle against the four hundred children represent the character of the solar region of the Aztecs in that the daily sunrise was viewed as a celestial battle against the moon (Coyolxauhqui) and the stars (Centzon Huitznahua).

[35] Both versions tell of the origin of human sacrifice at the sacred place, Coatepec, during the rise of the Aztec nation and at the foundation of Tenochtitlan.

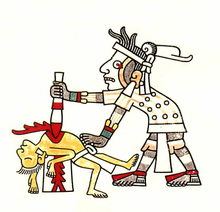

In art and iconography, Huitzilopochtli could be represented either as a hummingbird or as an anthropomorphic figure with just the feathers of such on his head and left leg, a black face, and holding a scepter shaped like a snake and a mirror.

[38] In the great temple his statue was decorated with cloth, feathers, gold, and jewels, and was hidden behind a curtain to give it more reverence and veneration.

Another variation lists him having a face that was marked with yellow and blue stripes and he carries around the fire serpent Xiuhcoatl with him.

[39] According to legend, the statue was supposed to be destroyed by the soldier Gil González de Benavides, but it was rescued by a man called Tlatolatl.

In fact, his hummingbird helmet was the one item that consistently defined him as Huitzilopochtli, the sun god, in artistic renderings.

[40] He is usually depicted as holding a shield adorned with balls of eagle feathers, a homage to his mother and the story of his birth.

People decorated their homes and trees with paper flags; there were ritual races, processions, dances, songs, prayers, and finally human sacrifices.

[citation needed] According to the Ramírez Codex, in Tenochtitlan approximately sixty prisoners were sacrificed at the festivities.

Sacrifices were reported to be made in other Aztec cities, including Tlatelolco, Xochimilco, and Texcoco, but the number is unknown, and no currently available archeological findings confirm this.

For the reconsecration of Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan in 1487, dedicated to Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli, the Aztecs reported that they sacrificed about 20,400 prisoners over the course of four days.