Human genome

It also includes promoters and their associated gene-regulatory elements, DNA playing structural and replicatory roles, such as scaffolding regions, telomeres, centromeres, and origins of replication, plus large numbers of transposable elements, inserted viral DNA, non-functional pseudogenes and simple, highly repetitive sequences.

Most, but not all, genes have been identified by a combination of high throughput experimental and bioinformatics approaches, yet much work still needs to be done to further elucidate the biological functions of their protein and RNA products.

[4][3] The human Y chromosome, consisting of 62,460,029 base pairs from a different cell line and found in all males, was sequenced completely in January 2022.

Some types of non-coding DNA are genetic "switches" that do not encode proteins, but do regulate when and where genes are expressed (called enhancers).

Among the microsatellite sequences, trinucleotide repeats are of particular importance, as sometimes occur within coding regions of genes for proteins and may lead to genetic disorders.

For example, Huntington's disease results from an expansion of the trinucleotide repeat (CAG)n within the Huntingtin gene on human chromosome 4.

Such genomic studies have led to advances in the diagnosis and treatment of diseases, and to new insights in many fields of biology, including human evolution.

[64] In 2022, the Telomere-to-Telomere (T2T) consortium reported the complete sequence of a human female genome,[3] filling all the gaps in the X chromosome (2020) and the 22 autosomes (May 2021).

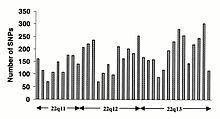

[72] Most studies of human genetic variation have focused on single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), which are substitutions in individual bases along a chromosome.

[74] A large-scale collaborative effort to catalog SNP variations in the human genome is being undertaken by the International HapMap Project.

These regions contain few genes, and it is unclear whether any significant phenotypic effect results from typical variation in repeats or heterochromatin.

Researchers published the first sequence-based map of large-scale structural variation across the human genome in the journal Nature in May 2008.

Structural variation refers to genetic variants that affect larger segments of the human genome, as opposed to point mutations.

That is, millions of base pairs may be inverted within a chromosome; ultra-rare means that they are only found in individuals or their family members and thus have arisen very recently.

Transitional changes are more common than transversions, with CpG dinucleotides showing the highest mutation rate, presumably due to deamination.

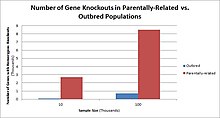

Challenges to characterizing and clinically interpreting knockouts include difficulty calling of DNA variants, determining disruption of protein function (annotation), and considering the amount of influence mosaicism has on the phenotype.

Some inherited variation influences aspects of our biology that are not medical in nature (height, eye color, ability to taste or smell certain compounds, etc.).

With these caveats, genetic disorders may be described as clinically defined diseases caused by genomic DNA sequence variation.

However, since there are many genes that can vary to cause genetic disorders, in aggregate they constitute a significant component of known medical conditions, especially in pediatric medicine.

The results of the Human Genome Project are likely to provide increased availability of genetic testing for gene-related disorders, and eventually improved treatment.

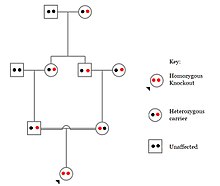

Parents can be screened for hereditary conditions and counselled on the consequences, the probability of inheritance, and how to avoid or ameliorate it in their offspring.

There are many different kinds of DNA sequence variation, ranging from complete extra or missing chromosomes down to single nucleotide changes.

It is generally presumed that much naturally occurring genetic variation in human populations is phenotypically neutral, i.e., has little or no detectable effect on the physiology of the individual (although there may be fractional differences in fitness defined over evolutionary time frames).

To molecularly characterize a new genetic disorder, it is necessary to establish a causal link between a particular genomic sequence variant and the clinical disease under investigation.

With the advent of the Human Genome and International HapMap Project, it has become feasible to explore subtle genetic influences on many common disease conditions such as diabetes, asthma, migraine, schizophrenia, etc.

[107] Around 20% of this figure is accounted for by variation within each species, leaving only ~1.06% consistent sequence divergence between humans and chimps at shared genes.

Humans have undergone an extraordinary loss of olfactory receptor genes during our recent evolution, which explains our relatively crude sense of smell compared to most other mammals.

Evolutionary evidence suggests that the emergence of color vision in humans and several other primate species has diminished the need for the sense of smell.

[111] In September 2016, scientists reported that, based on human DNA genetic studies, all non-Africans in the world today can be traced to a single population that exited Africa between 50,000 and 80,000 years ago.

[citation needed] It has also been used to show that there is no trace of Neanderthal DNA in the European gene mixture inherited through purely maternal lineage.