Hair

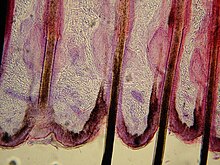

The human body, apart from areas of glabrous skin, is covered in follicles which produce thick terminal and fine vellus hair.

Hair grows everywhere on the external body except for mucous membranes and glabrous skin, such as that found on the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, and lips.

Hats and coats are still required while doing outdoor activities in cold weather to prevent frostbite and hypothermia, but the hair on the human body does help to keep the internal temperature regulated.

The opposite actions occur when the body is too warm; the arrector muscles make the hair lie flat on the skin which allows heat to leave.

Thick hair such as that of the lion's mane and grizzly bear's fur do offer some protection from physical damages such as bites and scratches.

The eyelash is to humans, camels, horses, ostriches etc., what whiskers are to cats; they are used to sense when dirt, dust, or any other potentially harmful object is too close to the eye.

It is currently unknown at what stage the synapsids acquired mammalian characteristics such as body hair and mammary glands, as the fossils only rarely provide direct evidence for soft tissues.

Skin impression of the belly and lower tail of a pelycosaur, possibly Haptodus shows the basal synapsid stock bore transverse rows of rectangular scutes, similar to those of a modern crocodile, so the age of acquirement of hair logically could not have been earlier than ≈299 ma, based on the current understanding of the animal's phylogeny.

The oldest undisputed known fossils showing unambiguous imprints of hair are the Callovian (late middle Jurassic) Castorocauda and several contemporary haramiyidans, both near-mammal cynodonts, giving the age as no later than ≈220 ma based on the modern phylogenetic understanding of these clades.

[52] Part of this evolution was the development of endurance running[53] and venturing out during the hot times of the day[54] that required efficient thermoregulation through perspiration.

Jablonski[55] asserts head hair was evolutionarily advantageous for pre-humans to retain because it protected the scalp as they walked upright in the intense African (equatorial) UV light.

While some might argue that, by this logic, humans should also express hairy shoulders because these body parts would putatively be exposed to similar conditions, the protection of the head, the seat of the brain that enabled humanity to become one of the most successful species on the planet (and which also is very vulnerable at birth) was arguably a more urgent issue (axillary hair in the underarms and groin were also retained as signs of sexual maturity).

Specifically, the results of that study suggest that this phenomenon resembles the passage of light through fiber optic tubes (which do not function as effectively when kinked or sharply curved or coiled).

Jablonski's assertions[55] suggest that the adjective "woolly" in reference to Afro-hair is a misnomer in connoting the high heat insulation derivable from the true wool of sheep.

Instead, the relatively sparse density of Afro-hair, combined with its springy coils actually results in an airy, almost sponge-like structure that in turn, Jablonski argues,[55] more likely facilitates an increase in the circulation of cool air onto the scalp.

Further, wet Afro-hair does not stick to the neck and scalp unless totally drenched and instead tends to retain its basic springy puffiness because it less easily responds to moisture and sweat than straight hair does.

Further, it is notable that the most pervasive expression of this hair texture can be found in sub-Saharan Africa; a region of the world that abundant genetic and paleo-anthropological evidence suggests, was the relatively recent (≈200,000-year-old) point of origin for modern humanity.

This points to a strong, long-term selective pressure that, in stark contrast to most other regions of the genomes of sub-Saharan groups, left little room for genetic variation at the determining loci.

A group of studies have recently shown that genetic patterns at the EDAR locus, a region of the modern human genome that contributes to hair texture variation among most individuals of East Asian descent, support the hypothesis that (East Asian) straight hair likely developed in this branch of the modern human lineage subsequent to the original expression of tightly coiled natural afro-hair.

[59][60][61] Specifically, the relevant findings indicate that the EDAR mutation coding for the predominant East Asian 'coarse' or thick, straight hair texture arose within the past ≈65,000 years, which is a time frame that covers from the earliest of the 'Out of Africa' migrations up to now.

This process is repeated several times over the course of many months to a couple of years with hair regrowing less frequently until it finally stops; this is used as a more permanent solution to waxing or shaving.

Although pattern baldness can be slowed down by drugs such as Finasteride and Minoxidil or treated with hair transplants, many men see this as unnecessary effort for the sake of vanity and instead shave their heads.

During the English Civil War, followers of Oliver Cromwell cropped their hair close to their head in an act of defiance against the curls and ringlets of the king's men, which led to them being nicknamed Roundheads.

[68] Recent isotopic analysis of hair is helping to shed further light on sociocultural interaction, giving information on food procurement and consumption in the 19th century.

The film Easy Rider (1969) includes the assumption that the two main characters could have their long hairs forcibly shaved with a rusty razor when jailed, symbolizing the intolerance of some conservative groups toward members of the counterculture.

[74] A case where a 14-year-old student was expelled from school in Brazil in the mid-2000s, allegedly because of his fauxhawk haircut, sparked national debate and legal action resulting in compensation.

[75][76] Women's hair may be hidden using headscarves, a common part of the hijab in Islam and a symbol of modesty required for certain religious rituals in Eastern Orthodoxy.

[80] For example, al-A'sha wrote a verse comparing a lover's hair to "a garden whose grapes dangle down upon me", but Bashshar ibn Burd considered this unusual.

[80] In Abbasid times, however, the imagery for hair expanded significantly - particularly for the then-fashionable "love-locks" (sudgh) framing the temples, which came into style at the court of the caliph al-Amin.

[80] Hair curls were compared to hooks and chains, letters (such as fa, waw, lam, and nun), scorpions, annelids, and polo sticks.