Human rights movement

The foundations of the global human rights movement involve resistance to: colonialism, imperialism, slavery, racism, segregation, patriarchy, and oppression of indigenous peoples.

[5][7] This organization was quickly embraced by the United States and European powers, perhaps as a way to counteract the Bolshevik call for global solidarity among workers.

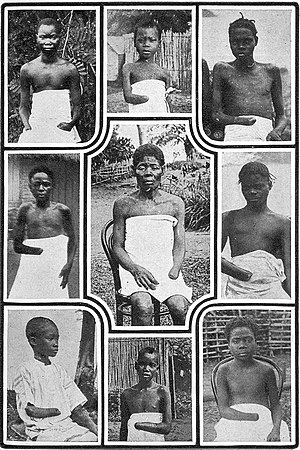

These photographs were passed among sympathetic Europeans and Americans, including Edmund Morel, Joseph Conrad, and Mark Twain—who wrote satirically as King Leopold: ...oh well, the pictures get sneaked around everywhere, in spite of all we can do to ferret them out and suppress them.

Du Bois, Walter White, and Paul Robeson joined with leaders of the African diaspora (from Haiti, Liberia, the Philippines, and elsewhere) to make a global demand for basic rights.

[11][12] Although the origins of this movement were multifaceted (owing strength both to the capitalist Marcus Garvey and to the more left-wing African Blood Brotherhood), a definitive moment of international solidarity came after Italy's annexation of Ethiopia in 1935.

[13] In the aftermath of World War II, the Pan-Africanist contingent played a major role in causing the United Nations to explicitly protect "human rights" in its founding documents.

[12] Representatives of small countries (particularly from Latin America), as well as Du Bois and other activists, were unhappy with the version of human rights envisioned for the UN Charter at Dumbarton Oaks in 1944.

Human rights language became an international standard, which could be used by great powers or by people's movements to make demands.

In 1951, Du Bois, William L. Patterson and the CRC presented a document called "We Charge Genocide", which accused the US of complicity with ongoing systematic violence against African Americans.

[12] An Appeal for Human Rights, published by Atlanta students in 1960, is cited as a key moment in beginning the wave of nonviolent direct actions that swept the American South.

[23] In 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. began to argue that the concept of "civil rights" was laden with isolating, individualistic capitalist values.

"[24] For King, who began to organize the multi-racial Poor People's Campaign just weeks before his April 1968 assassination, human rights required economic justice in addition to de jure equality.

[26] Some of the events of the 1970s, which gave global prominence to the human movements issue, included the abuses of Chilean Augusto Pinochet's and American Richard Nixon's administrations; the signing of the Helsinki Accords (1975) between the West and the USSR; the Soweto riots in South Africa; the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Amnesty International (1977); and the emergence of the Democracy Wall movement in China.

[30] Since the end of the Cold War, the issues of human rights have been present in a number of major political and military conflicts, debated by global public opinion, from Kosovo to Iraq, Afghanistan, the Congo and Darfur.

[31] Originally, most international human rights organizations came from France and the UK; since the 1970s American organizations moved beyond rights for Americans to partake in the international scene, and around the turn of the century, as noted by Neier, "the movement became so global in character that it is no longer possible to ascribe leadership to any particular [national or regional] segment".

In many cases, for example the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, women's groups were some of the most prominent advocates of human rights in general.

[36] The authority of the United Nations human rights framework diminished in the 1990s, partly due to the emphasis on economic liberalization that followed the Cold War.

[42] The human rights movement has historically focused on abuses by states, and some have argued that it has not attended closely enough to the actions of corporations.

[54][55] Makau Mutua has written: As currently constituted and deployed, the human rights movement will ultimately fail because it is perceived as an alien ideology in non-Western societies.

Kennedy also argues that this vocabulary can be "misused, distorted, or co-opted", and that framing issues in terms of human rights may narrow the field of possibility and exclude other narratives.