Human vestigiality

Charles Darwin listed a number of putative human vestigial features, which he termed rudimentary, in The Descent of Man (1871).

These included the muscles of the ear; wisdom teeth; the appendix; the tail bone; body hair; and the semilunar fold in the corner of the eye.

This book contains a list of 86 human organs he considered vestigial, which he called "wholly or in part functionless, some appearing in the Embryo alone, others present during Life constantly or inconstantly.

[5][6] Examples included: Historically, there was a trend not only to dismiss the appendix as being uselessly vestigial, but an anatomical hazard liable to dangerous inflammation.

The organ's patent liability to appendicitis and poorly understood role left it open to blame for a number of possibly unrelated conditions.

For example, in 1916, a surgeon claimed that removal of the appendix had cured several cases of trifacial neuralgia and other nerve pain about the head and face, even though he said the evidence for appendicitis in those patients was inconclusive.

In 1916, an author found it necessary to argue against the idea that the colon had no important function and that "the ultimate disappearance of the appendix is a coordinate action and not necessarily associated with such frequent inflammations as we are witnessing in the human".

Around 1920, the surgeon Kenelm Hutchinson Digby documented previous observations, going back more than 30 years, that suggested lymphatic tissues, such as the tonsils and appendix, might have substantial immunological functions.

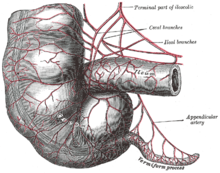

[12] Some herbivorous animals, such as rabbits, have a terminal vermiform appendix and cecum that apparently bear patches of tissue with immune functions and that may also be important in maintaining the composition of intestinal flora.

[13] As shown in the accompanying pictures, the human appendix typically is about comparable to that of the rabbit's in size, though the caecum is reduced to a single bulge where the ileum empties into the colon.

It is widely present in Euarchontoglires (a superorder of mammals that includes rodents, lagomorphs and primates) and has also evolved independently in the diprotodont marsupials and monotremes, and is highly diverse in size and shape, which could suggest it is not vestigial.

The common postulation is that their skulls had larger jaws with more teeth, which were possibly used to help chew down foliage to compensate for a lack of ability to efficiently digest the cellulose that makes up a plant cell wall.

[25] Agenesis (failure to develop) of wisdom teeth in human populations ranges from zero in Tasmanian Aboriginals to nearly 100% in indigenous Mexicans.

[27] In some animals, the vomeronasal organ (VNO) is part of a second, completely separate sense of smell, known as the accessory olfactory system.

[36] Among studies that use microanatomical methods, there is no reported evidence that human beings have active sensory neurons like those in other animals' working vomeronasal systems.

[36][37] Furthermore, no evidence suggests there are nerve and axon connections between any existing sensory receptor cells in the adult human VNO and the brain.

[40] Humans and other primates such as the orangutan and chimpanzee however have ear muscles that are minimally developed and non-functional, yet still large enough to be identifiable.

In humans there is variability in these muscles, such that some people are able to move their ears in various directions, and it can be possible for others to gain such movement by repeated trials.

have hypothesized that the persistence of the hymen may be to provide temporary protection from infection, as it separates the vaginal lumen from the urogenital sinus cavity during development.

[citation needed] In many animals, the upper lip and sinus area is associated with whiskers or vibrissae which serve a sensory function.

Based on histological studies of the upper lips of 20 cadavers, Tamatsu et al. found that structures resembling such muscles were present in 35% (7/20) of their specimens.

It is believed that this muscle actively participated in the arboreal locomotion of primates, but currently has no function, because it does not provide more grip strength.

In a morphological study of 100 Japanese cadavers, it was found that 86% of fibers identified were solid and bundled in the appropriate way to facilitate speech and mastication.

[69][70] One 2021 report demonstrated that all healthy young men and women who participated in an anatomic study of the front surface of the body exhibited 8 pairs of focal fat mounds running along the embryological mammary ridges from axillae to the upper inner thighs.

[76][77] An ancestral primate would have had sufficient body hair to which an infant could cling, unlike modern humans, thus allowing its mother to escape from danger, such as climbing up a tree in the presence of a predator without having to occupy her hands holding her baby.

[78] Amphibians such as tadpoles gulp air and water across their gills via a rather simple motor reflex akin to mammalian hiccuping.

Additionally, hiccups and amphibian gulping are inhibited by elevated CO2 and may be stopped by GABAB receptor agonists, illustrating a possible shared physiology and evolutionary heritage.

These proposals may explain why premature infants spend 2.5% of their time hiccuping, possibly gulping like amphibians, as their lungs are not yet fully formed.

This hypothesis has been questioned because of the existence of the afferent loop of the reflex, the fact that it does not explain the reason for glottic closure, and because the very short contraction of the hiccup is unlikely to have a significant strengthening effect on the slow-twitch muscles of respiration.