Humanitarian intervention

[1] Attempts to establish institutions and political systems to achieve positive outcomes in the medium- to long-run, such as peacekeeping, peace-building and development aid, do not fall under this definition of a humanitarian intervention.

[2] Nonetheless, there is a general consensus on some of its essential characteristics:[3] The customary international law concept of humanitarian intervention dates back to Hugo Grotius and the European politics in the 17th century.

[4][5] However, that customary law has been superseded by the UN Charter, which prohibits the use of force in international relations, subject to two exhaustive exceptions: UN Security Council action taken under Chapter VII, and self-defence against an armed attack.

[8] Over the course of the 20th century (in particular after the end of the Cold War), subjects perceived worthy of humanitarian intervention expanded beyond religiously and ethnically similar groups to encompass all peoples.

[9] Moreover, it has sparked normative and empirical debates over its legality, the ethics of using military force to respond to human rights violations, when it should occur, who should intervene,[10] and whether it is effective.

He was also instrumental in the outcome of the St. Petersburg Protocol 1826, in which Russia and Britain agreed to mediate between the Ottomans and the Greeks on the basis of complete autonomy of Greece under Turkish sovereignty.

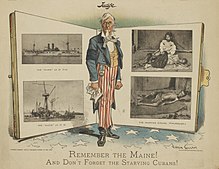

Lurid reports began to appear in newspapers, especially accounts by the investigative journalist William Thomas Stead in the Northern Echo, and protest meetings were called across the country.

[18] Despite the unprecedented demonstration of the strength of public opinion and the media, the Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli remained an unmoved practitioner of realpolitik, and considered British interests to lie in the preservation of Ottoman sovereignty in Eastern Europe.

This thorough riddance, this most blessed deliverance, is the only reparation we can make to those heaps and heaps of dead, the violated purity alike of matron and of maiden and of child; to the civilization which has been affronted and shamed; to the laws of God, or, if you like, of Allah; to the moral sense of mankind at large.Rising Great Power tensions in the early 20th century and the interwar period led to a breakdown in the concerted will of the international community to enforce considerations of a humanitarian nature.

The only test possessing any real value, of a people's having become fit for popular institutions, is that they, or a sufficient portion of them to prevail in the contest, are willing to brave labour and danger for their liberation.

John Rawls, one of the most influential political philosophers of the twentieth century, offers his theory of humanitarian intervention based on the notion of "well-ordered society."

On the other hand, expansionist or human rights violating regimes are not shielded from the international law: in grave cases such as ethnic cleansing, coercive intervention by others is legitimate.

Legal scholar Eric Posner also points out that countries tend to hold different views of human rights and public good, so to establish a relatively simple set of rules that reflects shared ethics is not likely to succeed.

[27] According to constructivist theorists, a state's self-interest is also defined by its identity as well as shared values and principles, which include promotion of democracy, freedom and human rights.

[10] Liberalism can be perceived as one of humanitarian intervention's ethical sources, which challenges the norms and methods of sovereign states’ governance together with its existence in the case where one of many nationalities experience oppression.

Certain liberalists even value national self-determination higher than an individual's right to democratic government, refusing the ethical origin of an intervention when only democracy is at risk.

However, idealism is often seen as too simplified and narrow since it claims that intervention has to follow purely altruistic motives where people selflessly want to help other individuals regardless of their race, religion or nationality.

The reference to the "right" of humanitarian intervention was, in the post Cold-War context, for the first time invoked in 1990 by the UK delegation after Russia and China had failed to support a no-fly zone over Iraq.

[28] Although most writers agree that humanitarian interventions should be undertaken multilaterally, ambiguity remains over which particular agents – the UN, regional organizations, or a group of states – should act in response to mass violations of human rights.

According to, the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide, the term was defined as acts “committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national ethnic, racial, or religious group.” However, the norm has been challenged.

The authors are critical of the RAND Corporation report Beginner's Guide to Nation-Building and argue every intervention situation is different based on the local political economy and there is not one universal approach that always works.

[51] Inter-governmental bodies and commission reports composed by persons associated with governmental and international careers have rarely discussed the distorting selectivity of geopolitics behind humanitarian intervention nor potential hidden motivations of intervening parties.

[54] Anne Orford's work is a major contribution along these lines, demonstrating the extent to which the perils of the present for societies experiencing humanitarian catastrophes are directly attributable to the legacy of colonial rule.

In the name of reconstruction, a capitalist set of constraints is imposed on a broken society that impairs its right of self-determination and prevents its leadership from adopting an approach to development that benefits the people of the country rather than makes foreign investors happy.

[55] Others argue that dominant countries, especially the United States and its coalition partners, are using humanitarian pretexts to pursue otherwise unacceptable geopolitical goals and to evade the non-intervention norm and legal prohibitions on the use of international force.

They argue that the United States has continued to act with its own interests in mind, with the only change being that humanitarianism has become a legitimizing ideology for projection of U.S. hegemony in a post–Cold War world.

[59] These critics argue that there is a tendency for the concept to be invoked in the heat of action, giving the appearance of propriety for Western television viewers, but that it neglects the conflicts that are forgotten by the media or occur based on chronic distresses rather than sudden crises.

[61] Castan Pinos claims that "humanitarian" interventions generate a multiplicity of collateral effects, including civilian deaths, conflict-aggravation, violence spill-over into neighbouring regions and mutual distrust between great powers.

[62] Jeremy Weinstein, a political scientist at Stanford University, has argued for "autonomous recovery": although the number of civilian deaths rises when violence between rebel groups is left unchecked, the eventual victors can develop institutions and set the terms of their rule in a self-enforcing manner.

These critics argue that the norm of non-intervention and the primacy of sovereign equality is something still cherished by the vast majority of states, which see humanitarian intervention not as a growing awareness of human rights, but a regression to the selective adherence to sovereignty of the pre–UN Charter world.