Ecological niche

[8][7] The term was coined by the naturalist Roswell Hill Johnson[9] but Joseph Grinnell was probably the first to use it in a research program in 1917, in his paper "The niche relationships of the California Thrasher".

Its 'niche' is defined by the felicitous complementing of the thrasher's behavior and physical traits (camouflaging color, short wings, strong legs) with this habitat.

[11] Variables of interest in this niche class include average temperature, precipitation, solar radiation, and terrain aspect which have become increasingly accessible across spatial scales.

[12] However, it is increasingly acknowledged that climate change also influences species interactions and an Eltonian perspective may be advantageous in explaining these processes.

In 1927 Charles Sutherland Elton, a British ecologist, defined a niche as follows: "The 'niche' of an animal means its place in the biotic environment, its relations to food and enemies.

[16] Because adjustments in biotic interactions inevitably change abiotic factors, Eltonian niches can be useful in describing the overall response of a species to new environments.

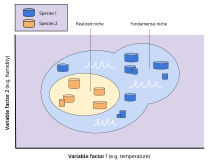

The Hutchinsonian niche is an "n-dimensional hypervolume", where the dimensions are environmental conditions and resources, that define the requirements of an individual or a species to practice its way of life, more particularly, for its population to persist.

[1][20][23] An organism free of interference from other species could use the full range of conditions (biotic and abiotic) and resources in which it could survive and reproduce which is called its fundamental niche.

[24] Hutchinson used the idea of competition for resources as the primary mechanism driving ecology, but overemphasis upon this focus has proved to be a handicap for the niche concept.

[20] In particular, overemphasis upon a species' dependence upon resources has led to too little emphasis upon the effects of organisms on their environment, for instance, colonization and invasions.

For example, the niche that was left vacant by the extinction of the tarpan has been filled by other animals (in particular a small horse breed, the konik).

The framework centers around "consumer-resource models" which largely split a given ecosystem into resources (e.g. sunlight or available water in soil) and consumers (e.g. any living thing, including plants and animals), and attempts to define the scope of possible relationships that could exist between the two groups.

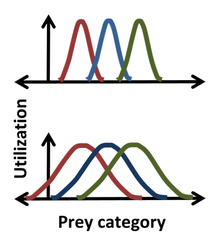

[34] The competitive exclusion principle states that if two species with identical niches (ecological roles) compete, then one will inevitably drive the other to extinction.

[41] A vague answer to this question is that the more similar two species are, the more finely balanced the suitability of their environment must be in order to allow coexistence.

[42][43] To understand the mechanisms of niche differentiation and competition, much data must be gathered on how the two species interact, how they use their resources, and the type of ecosystem in which they exist, among other factors.

In addition, several mathematical models exist to quantify niche breadth, competition, and coexistence (Bastolla et al. 2005).

[48] Simonsen discusses how plants accomplish root communication with the addition of beneficial rhizobia and fungal networks and the potential for different genotypes of the kin plants, such as the legume M. Lupulina, and specific strains of nitrogen fixing bacteria and rhizomes can alter relationships between kin and non-kin competition.

However, Andrewartha and Birch (1954,1984)[63][64] and others have pointed out that most natural populations usually don't even approach exhaustion of resources, and too much emphasis on interspecific competition is therefore wrong.

Evidence for niche segregation as the result of reinforcement of reproductive barriers is especially convincing in those cases in which such differences are not found in allopatric but only in sympatric locations.

The only limiting factor is space for attachment, since food (blood, mucus, fast regenerating epithelial cells) is in unlimited supply as long as the fish is alive.

Coexistence may be possible through a combination of non-limiting food and habitat resources and high rates of predation and parasitism, though this has not been demonstrated.

[76] However, niche differentiation is a critically important ecological idea which explains species coexistence, thus promoting the high biodiversity often seen in many of the world's biomes.

Other examples of nearly identical species clusters occupying the same niche were water beetles, prairie birds and algae.

The fundamental geographic range of a species is the area it occupies in which environmental conditions are favorable, without restriction from barriers to disperse or colonize.

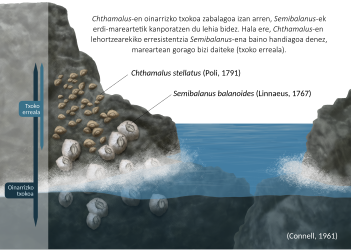

An early study on ecological niches conducted by Joseph H. Connell analyzed the environmental factors that limit the range of a barnacle (Chthamalus stellatus) on Scotland's Isle of Cumbrae.

[78] In his experiments, Connell described the dominant features of C. stellatus niches and provided explanation for their distribution on intertidal zone of the rocky coast of the Isle.

Connell described the upper portion of C. stellatus's range is limited by the barnacle's ability to resist dehydration during periods of low tide.

The lower portion of the range was limited by interspecific interactions, namely competition with a cohabiting barnacle species and predation by a snail.

[78] By removing the competing B. balanoides, Connell showed that C. stellatus was able to extend the lower edge of its realized niche in the absence of competitive exclusion.

These factors may include descriptions of the organism's life history, habitat, trophic position (place in the food chain), and geographic range.