Rings of Saturn

In September 2023, astronomers reported studies suggesting that the rings of Saturn may have resulted from the collision of two moons "a few hundred million years ago".

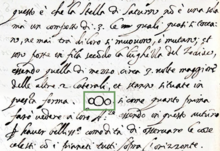

Galileo used the anagram "smaismrmilmepoetaleumibunenugttauiras" for Altissimum planetam tergeminum observavi ("I have observed the most distant planet to have a triple form") for discovering the rings of Saturn.

[12] Huygens began grinding lenses with his father Constantijn in 1655 and was able to observe Saturn with greater detail using a 43× power refracting telescope that he designed himself.

[13] Three years later, he revealed it to mean Annulo cingitur, tenui, plano, nusquam coherente, ad eclipticam inclinato ("[Saturn] is surrounded by a thin, flat, ring, nowhere touching [the body of the planet], inclined to the ecliptic").

[14][4][15] He published his ring hypothesis in Systema Saturnium (1659) which also included his discovery of Saturn's moon, Titan, as well as the first clear outline of the dimensions of the Solar System.

[32] In September 2023, astronomers reported studies suggesting that the rings of Saturn may have resulted from the collision of two moons "a few hundred million years ago".

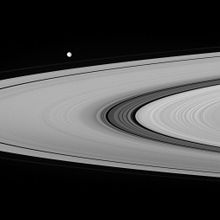

[5][6] Saturn's axial tilt is 26.7°, meaning that widely varying views of the rings, of which the visible ones occupy its equatorial plane, are obtained from Earth at different times.

The most recent ring plane crossings were on 22 May 1995, 10 August 1995, 11 February 1996 and 4 September 2009; upcoming events will occur on 23 March 2025, 15 October 2038, 1 April 2039 and 9 July 2039.

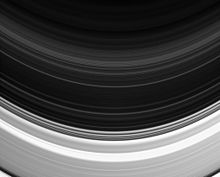

With an estimated local thickness of as little as 10 meters (32' 10")[40] and as much as 1 km (1093 yards),[41] they are composed of 99.9% pure water ice with a smattering of impurities that may include tholins or silicates.

Some gaps are cleared out by the passage of tiny moonlets such as Pan,[48] many more of which may yet be discovered, and some ringlets seem to be maintained by the gravitational effects of small shepherd satellites (similar to Prometheus and Pandora's maintenance of the F ring).

A hypothesis originally proposed by Édouard Roche in the 19th century is that the rings were once a moon of Saturn (named Veritas, after a Roman goddess who hid in a well).

[citation needed] A more traditional version of the disrupted-moon hypothesis is that the rings are composed of debris from a moon 400 to 600 km (200 to 400 miles) in diameter, slightly larger than Mimas.

[63] A more recent variant of this type of hypothesis by R. M. Canup is that the rings could represent part of the remains of the icy mantle of a much larger, Titan-sized, differentiated moon that was stripped of its outer layer as it spiraled into the planet during the formative period when Saturn was still surrounded by a gaseous nebula.

[68] The Cassini UVIS team, led by Larry Esposito, used stellar occultation to discover 13 objects, ranging from 27 meters (89') to 10 km (6 miles) across, within the F ring.

One mechanism involves gravity pulling electrically charged water ice grains down from the rings along planetary magnetic field lines, a process termed 'ring rain'.

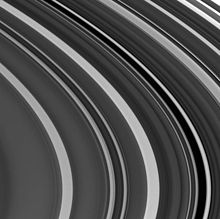

[88][89] The waves are interpreted as a spiral pattern of vertical corrugations of 2 to 20 m amplitude;[90] the fact that the period of the waves is decreasing over time (from 60 km; 40 miles in 1995 to 30 km; 20 miles by 2006) allows a deduction that the pattern may have originated in late 1983 with the impact of a cloud of debris (with a mass of ≈1012 kg) from a disrupted comet that tilted the rings out of the equatorial plane.

The leading hypothesis regarding the spokes' composition is that they consist of microscopic dust particles suspended away from the main ring by electrostatic repulsion, as they rotate almost synchronously with the magnetosphere of Saturn.

Suggestions that the spokes may be a seasonal effect, varying with Saturn's 29.7-year orbit, were supported by their gradual reappearance in the later years of the Cassini mission.

This ringlet exhibits irregular azimuthal variations of geometrical width and optical depth, which may be caused by the nearby 2:1 resonance with Mimas and the influence of the eccentric outer edge of the B-ring.

[133] In 2008, further dynamism was detected, suggesting that small unseen moons orbiting within the F Ring are continually passing through its narrow core because of perturbations from Prometheus.

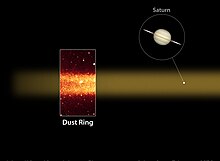

"[139] A faint dust ring is present around the region occupied by the orbits of Janus and Epimetheus, as revealed by images taken in forward-scattered light by the Cassini spacecraft in 2006.

"[150] A reanalysis of Feibelman's original observations, conducted in anticipation of the coming Saturn flyby by Pioneer 11, once again called the evidence for this outer ring "shaky.

"[151] Even polarimetric observations by Pioneer 11 failed to conclusively identify E Ring during its 1979 flyby, though "its existence was inferred from [particle, radiation, and magnetic field measurements].

In 2005, the source of the E Ring's material was determined to be cryovolcanic plumes[154][155] emanating from the "tiger stripes" of the south polar region of the moon Enceladus.

[167][168][169] Saturn's second largest moon Rhea has been hypothesized to have a tenuous ring system of its own consisting of three narrow bands embedded in a disk of solid particles.

[170][171] These putative rings have not been imaged, but their existence has been inferred from Cassini observations in November 2005 of a depletion of energetic electrons in Saturn's magnetosphere near Rhea.

The Magnetospheric Imaging Instrument (MIMI) observed a gentle gradient punctuated by three sharp drops in plasma flow on each side of the moon in a nearly symmetric pattern.

This could be explained if they were absorbed by solid material in the form of an equatorial disk containing denser rings or arcs, with particles perhaps several decimeters to approximately a meter in diameter.

A more recent piece of evidence consistent with the presence of Rhean rings is a set of small ultraviolet-bright spots distributed in a line that extends three quarters of the way around the moon's circumference, within 2 degrees of the equator.

[172] However, targeted observations by Cassini of the putative ring plane from several angles have turned up nothing, suggesting that another explanation for these enigmatic features is needed.