Pale Blue Dot

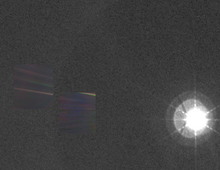

In the photograph, Earth's apparent size is less than a pixel; the planet appears as a tiny dot against the vastness of space, among bands of sunlight reflected by the camera.

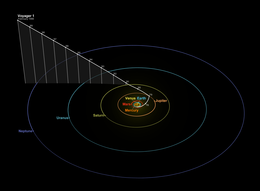

After fulfilling its primary mission and as it ventured out of the Solar System, the decision to turn its camera around and capture one last image of Earth emerged, in part due to Sagan's proposition.

[2][3] Over the years, the photograph has been revisited and celebrated on multiple occasions, with NASA acknowledging its anniversaries and presenting updated versions, enhancing its clarity and detail.

[6] Its mission has been extended and continues to this day, with the aim of investigating the boundaries of the Solar System, including the Kuiper belt, the heliosphere and interstellar space.

[9] He acknowledged that such a picture would not have had much scientific value, as the Earth would appear too small for Voyager's cameras to make out any detail, but it would be meaningful as a perspective on humanity's place in the universe.

[9] Although many in NASA's Voyager program were supportive of the idea, there were concerns that taking a picture of Earth so close to the Sun risked damaging the spacecraft's imaging system irreparably.

It was not until 1989 that Sagan's idea was put in motion, but then instrument calibrations delayed the operation further, and the personnel who devised and transmitted the radio commands to Voyager 1 were also being laid off or transferred to other projects.

[13][14][15] The challenge was that, as the mission progressed, the objects to be photographed would increasingly be farther away and would appear fainter, requiring longer exposures and slewing (panning) of the cameras to achieve acceptable quality.

[16] The design of the command sequence to be relayed to the spacecraft and the calculations for each photograph's exposure time were developed by space scientists Candy Hansen of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Carolyn Porco of the University of Arizona.

Then, between March and May 1990, Voyager 1 returned 60 frames back to Earth, with the radio signal traveling at the speed of light for nearly five and a half hours to cover the distance.

The light bands across the photograph are an artifact, the result of sunlight reflecting off parts of the camera and its sunshade, due to the relative proximity between the Sun and the Earth.

The wide-angle photograph was taken with the darkest filter (a methane absorption band) and the shortest possible exposure (5 milliseconds), to avoid saturating the camera's vidicon tube with scattered sunlight.

Even so, the result was a bright burned-out image with multiple reflections from the optics in the camera and the Sun that appears far larger than the actual dimension of the solar disk.

[23] In his 1994 book, Pale Blue Dot, Carl Sagan comments on what he sees as the greater significance of the photograph, writing: From this distant vantage point, the Earth might not seem of any particular interest.

The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every "superstar", every "supreme leader", every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there – on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.