Hybrid solar cell

Hybrid photovoltaics have organic materials that consist of conjugated polymers that absorb light as the donor and transport holes.

[9] The structure of mesoporous thin film solar cells typically includes a porous inorganic that is saturated with organic surfactant.

Problems with these cells include their random ordering and the difficulty of controlling their nanoscale structure to promote charge conduction.

To produce this type of cell with practical efficiencies, larger organic surfactants that absorb more of the visible spectrum must be deposited between the layers of electron-accepting inorganic.

Researchers grew nanostructure-based solar cells that use ordered nanostructures like nanowires or nanotubes of inorganic surrounding by electron-donating organics utilizing self-organization processes.

Ordered nanostructures offer the advantage of directed charge transport and controlled phase separation between donor and acceptor materials.

[11] The nanowire-based morphology offers reduced internal reflection, facile strain relaxation and increased defect tolerance.

The ability to make single-crystalline nanowires on low-cost substrates such as aluminum foil and to relax strain in subsequent layers removes two more major cost hurdles associated with high-efficiency cells.

Second, contact resistance between each layer in the device should be minimized to offer higher fill factor and power conversion efficiency.

Third, charge-carrier mobility should be increased to allow the photovoltaics to have thicker active layers while minimizing carrier recombination and keeping the series resistance of the device low.

Nanoparticles are a class of semiconductor materials whose size in at least one dimension ranges from 1 to 100 nanometers, on the order of exciton wavelengths.

This size control creates quantum confinement and allows for the tuning of optoelectronic properties, such as band gap and electron affinity.

In this case, the nanoparticles take the place of the fullerene based acceptors used in fully organic polymer solar cells.

Different structures change the conversion efficiency by effecting nanoparticle dispersion in the polymer and providing pathways for electron transport.

[14] Fabrication methods include mixing the two materials in a solution and spin-coating it onto a substrate, and solvent evaporation (sol-gel).

[3][14] Inorganic semiconductor nanoparticles used in hybrid cells include CdSe (size ranges from 6–20 nm), ZnO, TiO, and PbS.

The particles need to be dispersed in order to maximize interface area, but need to aggregate to form networks for electron transport.

The metal provides a higher electric field at the CNT-polymer interface, accelerating the exciton carriers to transfer them more effectively to the CNT matrix.

[22] The semiconducting single walled CNT (SWCNT) is a potentially attractive material for photovoltaic applications for the unique structural and electrical properties.

A strong built-in electric field in SWCNT for efficient photogenerated electron-hole pair separation has been demonstrated by using two asymmetrical metal electrodes with high and low work functions.

The passivation layer required to prevent CNT oxidation may reduce the optical transparency of the electrode region and lower the photovoltaic efficiency.

(A p-n junction creates an internal built-in potential, providing a pathway for efficient carrier separation within the photovoltaic.)

A strong built-in electric field covering the whole SWCNT channel is formed for high-efficiency carrier separation.

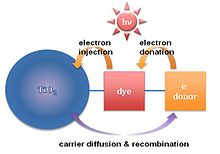

Molecular sensitizers (dye molecules) attached to the semiconductor surface are used to collect a greater portion of the spectrum.

In order to make a photovoltaic cell, molecular sensitizers (dye molecules) are attached to the titania surface.

Many organic materials have been tested to obtain a high solar-to-energy conversion efficiency in dye synthesized solar cells based on mesoporous titania thin film.

[27] Efficiency factors demonstrated for dye-sensitized solar cells are Liquid organic electrolytes contain highly corrosive iodine, leading to problems of leakage, sealing, handling, dye desorption, and maintenance.

For solid-state dye sensitized solar cells, the first challenge originates from disordered titania mesoporous structures.

The second challenge comes from developing the solid electrolyte, which is required to have these properties: In 2008, scientists were able to create a nanostructured lamellar structure that provides an ideal design for bulk heterojunction solar cells.

The thicknesses of the layers (about 1–3 nm) are well within the exciton diffusion length, which ideally minimizes recombination among charge carriers.