Viral vector

Viruses have evolved specialized molecular mechanisms to transport their genomes into infected hosts, a process termed transduction.

Different viral vector classes vary widely in strengths and limitations, suiting some to specific applications.

Further development was temporarily halted by a recombinant DNA research moratorium following the Asilomar Conference and stringent National Institutes of Health regulations.

Although the 1990s saw significant advances in viral vectors, clinical trials had a number of setbacks, culminating in Jesse Gelsinger's death.

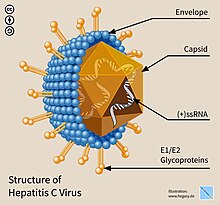

Viruses, infectious agents composed of a protein coat that encloses a genome, are the most numerous biological entities on Earth.

[11] Viral vector gene therapies may also be used for plants, tentatively enhancing crop performance or promoting sustainable production.

[11][13] Relative to other non-integrative gene therapy approaches, transgenes introduced by viral vectors offer multi-year long expression.

[15][16] Conventional vaccines are not suitable for protection against some pathogens due to unique immune evasion strategies and differences in pathogenesis.

[22] In the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic, viral vector vaccines played a fundamental role and were administered to billions of people, particularly in low and middle-income nations.

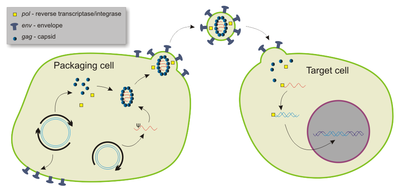

[23] Retroviruses—enveloped RNA viruses—are popular viral vector platforms due to their ability to integrate genetic material into the host genome.

[25] The most commonly used gammaretroviral vector is a modified Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV), able to transduce various mammalian cell types.

[26] Gammaretroviral vectors have been successfully applied to ex vivo hematopoietic stem cell to treat multiple genetic diseases.

[36] Adenoviral vectors display high transduction efficiency and transgene expression, and can infect both dividing and non-dividing cells.

[38] Its strong immunogenicity is particularly due to the transduction of dendritic cells (DC), upregulating the expression of both MHC I and II molecules and activating the DCs.

[41] While the activation of both innate and adaptive immune responses is an obstacle for many therapeutic applications, it makes adenenoviral vectors an ideal vaccine platform.

[43] The tropism of adeno-associated viral vectors can be tailored by creating recombinant versions from multiple serotypes, termed pseudotyping.

[43] Due to their ability to infect and induce longlasting effects within nondividing cells, AAVs are commonly used in basic neuroscience research.

[49][48] Moreover, manufacturing procedures developed to mass-produce smallpox vaccine stockpiles may expedite vaccinia viral vector production.

[52] As a vaccine platform, vaccinia vectors display highly effective transgene expression and create a robust immune response.

[50] The virus fast-acting: its life cycle produces mature progeny vaccinia within 6 hours, and has three viral spread mechanisms.

Although a CMV-based vaccine provided significant immunity against SIV—closely related to HIV—in macaques, development of CMV as a reliable vector was reported to still be in early stages as of 2020.

[61] These vectors have been employed for a range of applications, from increasing the aesthetic quality of ornamental plants to pest biocontrol, rapid expression of recombinant proteins and peptides, and to accelerate crop breeding.

[72] For viral vector production on a smaller, laboratory setting, static cell culture systems like Petri dishes are typically used.

[74] In 2017, The New York Times reported a manufacturing backlog of inactivated viruses, delaying some gene therapy trials by years.

[75] In 1972, Stanford University biochemist Paul Berg developed the first viral vector, incorporating DNA from the lambda phage into the polyomavirus SV40 to infect kidney cells maintained in culture.

[76][77][78] The implications of this achievement troubled scientists like Robert Pollack, who convinced Berg not to transduce DNA from SV40 into E. coli via a bacteriophage vector.

[81] In 1977, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) issued formal guidelines confining viral DNA cloning to rigid BSL-4 conditions, practically preventing such research.

[11] However, during a 1999 clinical trial at the University of Pennsylvania, Jesse Gelsinger died from a fatal reaction to an adenoviral vector-based gene therapy.

[84] Shortly thereafter, the field's reputation was further damaged when 5 children treated with a SCID gene therapy developed leukemia due to an issue with the retroviral vector.

[84][note 1] Viral vectors experienced a resurgence when they were successfully employed for ex vivo hematopoietic gene delivery in clinical settings.