Hyperboloid

A hyperboloid is the surface obtained from a hyperboloid of revolution by deforming it by means of directional scalings, or more generally, of an affine transformation.

Among quadric surfaces, a hyperboloid is characterized by not being a cone or a cylinder, having a center of symmetry, and intersecting many planes into hyperbolas.

In any case, the hyperboloid is asymptotic to the cone of the equations:

Otherwise, the axes are uniquely defined (up to the exchange of the x-axis and the y-axis).

It is a connected surface, which has a negative Gaussian curvature at every point.

The surface has two connected components and a positive Gaussian curvature at every point.

Cartesian coordinates for the hyperboloids can be defined, similar to spherical coordinates, keeping the azimuth angle θ ∈ [0, 2π), but changing inclination v into hyperbolic trigonometric functions: One-surface hyperboloid: v ∈ (−∞, ∞)

More generally, an arbitrarily oriented hyperboloid, centered at v, is defined by the equation

The eigenvectors of A define the principal directions of the hyperboloid and the eigenvalues of A are the reciprocals of the squares of the semi-axes:

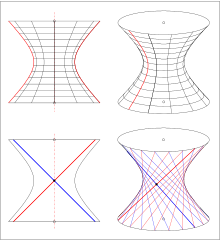

the hyperboloid is a surface of revolution and can be generated by rotating one of the two lines

A hyperboloid of one sheet is projectively equivalent to a hyperbolic paraboloid.

For simplicity the plane sections of the unit hyperboloid with equation

Obviously, any one-sheet hyperboloid of revolution contains circles.

This is also true, but less obvious, in the general case (see circular section).

The discussion of plane sections can be performed for the unit hyperboloid of two sheets with equation

which can be generated by a rotating hyperbola around one of its axes (the one that cuts the hyperbola) Obviously, any two-sheet hyperboloid of revolution contains circles.

This is also true, but less obvious, in the general case (see circular section).

Remark: A hyperboloid of two sheets is projectively equivalent to a sphere.

In spite of its positive curvature, the hyperboloid of two sheets with another suitably chosen metric can also be used as a model for hyperbolic geometry.

Imaginary hyperboloids are frequently found in mathematics of higher dimensions.

For example, in a pseudo-Euclidean space one has the use of a quadratic form:

As an example, consider the following passage:[4] ... the velocity vectors always lie on a surface which Minkowski calls a four-dimensional hyperboloid since, expressed in terms of purely real coordinates (y1, ..., y4), its equation is y21 + y22 + y23 − y24 = −1, analogous to the hyperboloid y21 + y22 − y23 = −1 of three-dimensional space.

A hyperboloid is a doubly ruled surface; thus, it can be built with straight steel beams, producing a strong structure at a lower cost than other methods.

Examples include cooling towers, especially of power stations, and many other structures.

In 1853 William Rowan Hamilton published his Lectures on Quaternions which included presentation of biquaternions.

The following passage from page 673 shows how Hamilton uses biquaternion algebra and vectors from quaternions to produce hyperboloids from the equation of a sphere: ... the equation of the unit sphere ρ2 + 1 = 0, and change the vector ρ to a bivector form, such as σ + τ √−1.

The equation of the sphere then breaks up into the system of the two following, and suggests our considering σ and τ as two real and rectangular vectors, such that

Hence it is easy to infer that if we assume σ || λ, where λ is a vector in a given position, the new real vector σ + τ will terminate on the surface of a double-sheeted and equilateral hyperboloid; and that if, on the other hand, we assume τ || λ, then the locus of the extremity of the real vector σ + τ will be an equilateral but single-sheeted hyperboloid.

The study of these two hyperboloids is, therefore, in this way connected very simply, through biquaternions, with the study of the sphere; ...In this passage S is the operator giving the scalar part of a quaternion, and T is the "tensor", now called norm, of a quaternion.

A modern view of the unification of the sphere and hyperboloid uses the idea of a conic section as a slice of a quadratic form.