Light cone

To uphold causality, Minkowski restricted spacetime to non-Euclidean hyperbolic geometry.

[1][page needed] Because signals and other causal influences cannot travel faster than light (see special relativity), the light cone plays an essential role in defining the concept of causality: for a given event E, the set of events that lie on or inside the past light cone of E would also be the set of all events that could send a signal that would have time to reach E and influence it in some way.

For example, at a time ten years before E, if we consider the set of all events in the past light cone of E which occur at that time, the result would be a sphere (2D: disk) with a radius of ten light-years centered on the position where E will occur.

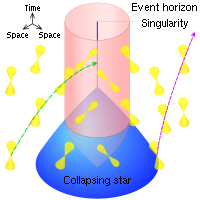

This can be visualized in 3-space if the two horizontal axes are chosen to be spatial dimensions, while the vertical axis is time.

If using a system of units where the speed of light in vacuum is defined as exactly 1, for example if space is measured in light-seconds and time is measured in seconds, then, provided the time axis is drawn orthogonally to the spatial axes, as the cone bisects the time and space axes, it will show a slope of 45°, because light travels a distance of one light-second in vacuum during one second.

Light cones also cannot all be tilted so that they are 'parallel'; this reflects the fact that the spacetime is curved and is essentially different from Minkowski space.

In vacuum regions (those points of spacetime free of matter), this inability to tilt all the light cones so that they are all parallel is reflected in the non-vanishing of the Weyl tensor.