Thrombophilia

[3] A significant proportion of the population has a detectable thrombophilic abnormality, but most of these develop thrombosis only in the presence of an additional risk factor.

[4][5] The most common conditions associated with thrombophilia are deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), which are referred to collectively as venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Depending on the size and the location of the clot, this may lead to sudden-onset shortness of breath, chest pain, palpitations and may be complicated by collapse, shock and cardiac arrest.

[2] Whether thrombophilia also increases the risk of arterial thrombosis (which is the underlying cause of heart attacks and strokes) is less well established.

[2][8][9] However, more recent data suggest some forms of inherited thrombophilia are associated with increased risk for arterial ischemic stroke.

[10] Thrombophilia has been linked to recurrent miscarriage,[11] and possibly various complications of pregnancy such as intrauterine growth restriction, stillbirth, severe pre-eclampsia and abruptio placentae.

[2] Protein C deficiency may cause purpura fulminans, a severe clotting disorder in the newborn that leads to both tissue death and bleeding into the skin and other organs.

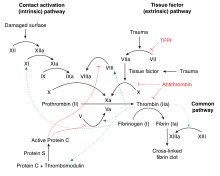

The most common types of congenital thrombophilia are those that arise as a result of overactivity of coagulation factors; hence they are considered "gain-of-function" alterations.

[1][16] Milder rare congenital thrombophilias are factor XIII mutation[16] and familial dysfibrinogenemia (an abnormal fibrinogen).

[16] It is unclear whether congenital disorders of fibrinolysis (the system that destroys clots) are major contributors to thrombosis risk.

[14] Congenital deficiency of plasminogen, for instance, mainly causes eye symptoms and sometimes problems in other organs, but the link with thrombosis has been more uncertain.

[19] Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is a rare condition resulting from acquired alterations in the PIGA gene, which plays a role in the protection of blood cells from the complement system.

For example, sickle-cell disease (caused by mutations of hemoglobin) is regarded as a mild prothrombotic state induced by impaired flow.

[2][16] A number of mechanisms have been proposed, such as activation of the coagulation system by cancer cells or secretion of procoagulant substances.

Obese people also have larger numbers of circulating microvesicles (fragments of damaged cells) that bear tissue factor.

[8][12][33] Recurrent thromboembolism, or thrombosis in unusual sites (e.g. the hepatic vein in Budd-Chiari syndrome), is a generally accepted indication for screening.

[12] In particular situations, such as retinal vein thrombosis, testing is discouraged altogether because thrombophilia is not regarded as a major risk factor.

[12] If cost-effectiveness (quality-adjusted life years in return for expenditure) is taken as a guide, it is generally unclear whether thrombophilia investigations justify the often high cost,[38] unless the testing is restricted to selected situations.

Thrombophilia testing after venous thromboembolism(VTE) provoked by surgery, on the other hand, is not recommended, because the risk of recurrence is low.

Some experts argue that unprovoked VTE requires indefinite (lifelong) anticoagulation and therefore performing thrombophilia testing will not affect management.

[41] Recurrent miscarriage is an indication for thrombophilia screening, particularly antiphospholipid antibodies (anti-cardiolipin IgG and IgM, as well as lupus anticoagulant), factor V Leiden and prothrombin mutation, activated protein C resistance and a general assessment of coagulation through an investigation known as thromboelastography.

[11] Women who are planning to use oral contraceptives do not benefit from routine screening for thrombophilias, as the absolute risk of thrombotic events is low.

[12] Thrombophilia screening in people with arterial thrombosis is generally regarded as unrewarding and is generally discouraged,[12] except possibly for unusually young patients (especially when precipitated by smoking or use of estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives) and those in whom revascularization, such as coronary arterial bypass, fails because of rapid occlusion of the graft.

In those with unprovoked and/or recurrent thrombosis, or those with a high-risk form of thrombophilia, the most important decision is whether to use anticoagulation medications, such as warfarin, on a long-term basis to reduce the risk of further episodes.

[3] Apart from the abovementioned forms of thrombophilia, the risk of recurrence after an episode of thrombosis is determined by factors such as the extent and severity of the original thrombosis, whether it was provoked (such as by immobilization or pregnancy), the number of previous thrombotic events, male sex, the presence of an inferior vena cava filter, the presence of cancer, symptoms of post-thrombotic syndrome, and obesity.

[44] When women experience recurrent pregnancy loss secondary to thrombophilia, some studies have suggested that low molecular weight heparin reduces the risk of miscarriage.

People with activated protein C resistance (usually resulting from factor V Leiden), in contrast, have a slightly raised absolute risk of thrombosis, with 15% having had at least one thrombotic event by the age of sixty.

The exact nature of these abnormalities remained elusive until the first form of thrombophilia, antithrombin deficiency, was recognized in 1965 by the Norwegian hematologist Olav Egeberg.

[4][5][48] Antiphospholipid syndrome was described in full in the 1980s, after various previous reports of specific antibodies in people with systemic lupus erythematosus and thrombosis.

Many studies had previously indicated that many people with thrombosis showed resistance activated protein C. In 1994 a group in Leiden, The Netherlands, identified the most common underlying defect—a mutation in factor V that made it resistant to the action of activated protein C. The defect was called factor V Leiden, as genetic abnormalities are typically named after the place where they are discovered.