Ion Luca Caragiale

[20] A similar opinion was expressed by Paul Zarifopol, who speculated that Caragiale's conservative mindset was possibly owed to the "lazyness of one true Oriental"[21] (elsewhere, he referred to the writer as "a lazy southerner, fitted with definitely supranormal intelligence and imagination").

[25] Two of his biographers, Zarifopol and Șerban Cioculescu, noted that a section of Caragiale's fairy tale Kir Ianulea was a likely self-reference: in that fragment of text, the Christian Devil, disguised as an Arvanite trader, is shown taking pride in his Romanian language skills.

[41] In 1866, Caragiale witnessed Cuza's toppling by a coalition of conservatives and liberals — as he later acknowledged in his Grand Hotel "Victoria Română", he and his friends agreed to support the move by voting "yes" during a subsequent plebiscite, and, with tacit approval from the new authorities, even did so several times each.

[62] Macedonski later alleged that, in his contributions to the liberal newspapers, the young writer had libeled several Conservative Party politicians—when researching this period, Șerban Cioculescu concluded that the accusation was false, and that only one polemical article on a political topic could be traced back to Caragiale.

[81] To varying degrees, they all complimented the main element of Junimist discourse, Maiorescu criticism of "forms without a foundation"—the concept itself referred to the negative impact of modernization, which, Junimea argued, had by then only benefited the upper strata of Romanian society, leaving the rest with an incomplete and increasingly falsified culture.

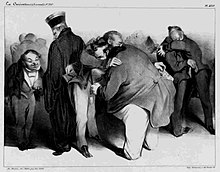

[3][108] During the same year, Caragiale's D-ale carnavalului, a lighter satire of suburban morals and amorous misadventures, was received with booing and heckling by members of the public — critics deemed it "immoral", due to its frank depiction of adultery gone unpunished.

[115] Despite his earlier conflicts with the National Liberals, Caragiale, who still faced problems in making a living, agreed to contribute pieces for the party press, and thus briefly associated with Voința Națională (a journal issued by historian and politician Alexandru Dimitrie Xenopol).

[122] Early in 1890, at the same time as his volume of collected works, Caragiale published and staged his rural-themed tragedy Năpasta — both writings were presented for consideration to the Romanian Academy, in view of receiving its annual prize, the Ion Heliade Rădulescu Award.

[143] During his short stay, he printed an unsigned sketch story, Cum se înțeleg țăranii ("How Peasants Communicate"), which mockingly recorded a lengthy and redundant dialog between two villagers,[144] as well as a portrait of the deceased politician Mihail Kogălniceanu, and a fairy tale inspired by the writings of Anton Pann.

[161] Nevertheless, he was distancing himself from the purest Junimist tenets, and took a favorable view of Romantic writers whom the society had criticized or ridiculed — among these, he indicated his personal rival Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu, whom he acknowledged to be among "the most remarkable figures of our literature", and Alexandru Odobescu.

[161] As editor of Epoca, he published works by Hasdeu alongside those of his other contemporaries and predecessors — Grigore Alexandrescu, Nicolae Filimon, Dinicu Golescu, Ion Heliade Rădulescu, Cilibi Moise, Costache Negruzzi, and Anton Pann.

[168] This material formed the bulk of his collected short prose volume, Momente și schițe, and notably comprised satirical pieces ridiculing the Romanian press' reaction to the activities of Boris Sarafov, a Macedonian-Bulgarian revolutionary who had attempted to set up a base in Romania.

[194] He did not however isolate himself completely, becoming very close to the group of Romanian students attending the University of Berlin and to other young people: among them were poet and essayist Panait Cerna, sociologist Dimitrie Gusti, musician Florica Musicescu, and Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea's son-in-law, the literary critic Paul Zarifopol.

[246] Caragiale's interest in Realism was however denied by some of his Junimist advocates, who attempted to link his entire work with Maiorescu's guidelines: on the basis of Schopenhauerian aesthetics, critic Mihail Dragomirescu postulated that his humor was pure, and did not draw on any special circumstance or context.

[268] Noting this, several critics believe that, in his O scrisoare pierdută, which depicts the battle between two unnamed political camps, the dramatist alluded to the conflict between Brătianu's moderates and Rosetti's extremists (as indicated by the fact that all the main characters attend the same rallies).

[272] Like Junimea, he was entirely opposed to the group of August Treboniu Laurian and other Transylvanian intellectuals, who attempted to reform the Romanian language by introducing new forms of speech and writing that aimed to return it closer to its Latin roots.

[262] This was for long disputed: rabbi and literary historian Moses Gaster attributed the pieces to Nicolae Xenopol, while researcher Șerban Cioculescu, who originally doubted them, eventually agreed that they formed an integral part of Caragiale's work.

[22] Caragiale contrasted the other major writers of his generation, including his friends Mihai Eminescu, Ioan Slavici, Barbu Ștefănescu Delavrancea, and Sămănătorul journal founder Alexandru Vlahuță, all of whom were advocating a return to the rural sphere and peasant traditionalism.

Literary critic Matei Călinescu believes that he genuinely admired În orașul cu trei sute de biserici ("In the City with Three Hundred Churches"), a free verse poem by the Symbolist Ion Minulescu.

[306] The writer had an unprecedented familiarity with the social environments, traits, opinions, manners of speech, means of expression and lifestyle choices of his day — from the rural atmosphere of his early childhood, going through his vast experience as a journalist, to the high spheres of politics (National Liberal as well as Conservative, Junimist as well as socialist).

[24][312] The author depicted the city in all stages of its development and in all its atmospheres — from nightlife to Căldură mare's midday torpor, from noisy slums and the Târgul Moșilor fête in Obor to the English-inspired tea parties of the urban elite.

[315] Tudor Vianu also noted that, among cities and towns, Caragiale preferred Bucharest and those provincial centers most exposed to Central European influences (specifically, the summer retreats in the Prahova Valley and other Wallachian stations on the way to Transylvania).

[252] In 1907, din primăvară până în toamnă, his late and disillusioned work, Caragiale lashed out at the traditional class of political clients, with an indictment which, Tudor Vianu believed, also served to identify the main focus of his other writings: "plebs incapable of work and lacking employment, impoverished suburban small traders and street vendors, petty dangerous agitators of the villages and of the areas adjacent to towns, bullying election agents; and then the hybrid product of all levels of schooling, semi-cultured intellectuals, lawyers and lawyerlings, professors, teachers and teacherlings, semi-illiterate and unfrocked priests, illiterate schoolteachers—all of them beer garden theorists; next come the great functionaries and the little clerks, most of them removable from office.

[322] In his words: "A wave of charm, of reconciliation with life passes above all [his characters], one which, if it only assumes light and superficial shapes, experienced by naive people with harmless manias, is a sign that the collective existence is taking place in shelter from the great trials.

[333] A similar view was expressed by Vianu's predecessor, Silvian Iosifescu, who also stressed that Caragiale always avoided applying the Naturalist technique to its fullest,[334] while George Călinescu himself believed that the characters' motivations in O făclie de Paște are actually physiological and ethnological.

[335] Maiorescu was especially fond of the way in which Caragiale balanced his personal perspective and the generic traits he emphasized: speaking of Leiba Zibal, the Jewish character in O făclie de Paște who defends himself out of fear, he drew a comparison with Shakespeare's Shylock.

[350] In parallel, Zarifopol argued, the writer had even allowed ironic reflections on the impact of various theories to seep into a more serious work, O făclie de Paște, where two students terrify the innkeeper Zibal by casually discussing anthropological criminology.

[365] Thus, Iancu Pampon, an assistant-barber and former police officer, and his female counterpart, the republican suburbanite Mița Baston, are determined to uncover their partners' amorous escapades, and their hectic inquiry combines real clues with figments of imagination, fits of passionate rage with moments of sad meditation, and violent threats with periods of resignation.

[366] Glimpses into this type of behavior have been noted in other plays by Caragiale: Cazimir placed emphasis on the fact that Farfuridi is shown to be extremely cautious towards all unplanned changes, and consumes much of his energy in preserving a largely pointless daily routine.

[398] Direct or covert depictions of Caragiale are also present in several fiction works, starting with a revue first shown during his lifetime,[399] and including novels by Goga, Slavici, N. Petrașcu, Emanoil Bucuța, Eugen Lovinescu, Constantin Stere, as well as a play by Camil Petrescu.