International Prototype of the Kilogram

The IPK is a roughly golfball-sized object made of a platinum–iridium alloy known as "Pt‑10Ir", which is 90% platinum and 10% iridium (by mass) and is machined into a right-circular cylinder with perpendicular height equal to its diameter of about 39 millimetres to reduce its surface area.

[8] The addition of 10% iridium improved upon the all-platinum Kilogramme des Archives by greatly increasing hardness while still retaining platinum's many virtues: extreme resistance to oxidation, extremely high density (almost twice as dense as lead and more than 21 times as dense as water), satisfactory electrical and thermal conductivities, and low magnetic susceptibility.

[12] The Metre Convention was signed on 20 May 1875 and further formalised the metric system (a predecessor to the SI), quickly leading to the production of the IPK.

The IPK is one of three cylinders made in London in 1879 by Johnson Matthey, which continued to manufacture nearly all of the national prototypes as needed until the new definition of the kilogram came into effect in 2019.

[13][14] In 1883, the mass of the IPK was found to be indistinguishable from that of the Kilogramme des Archives made eighty-four years prior, and was formally ratified as the kilogram by the 1st CGPM in 1889.

[26] Beyond the simple wear that check standards can experience, the mass of even the carefully stored national prototypes can drift relative to the IPK for a variety of reasons, some known and some unknown.

Since the IPK and its replicas are stored in air (albeit under two or more nested bell jars), they gain mass through adsorption of atmospheric contamination onto their surfaces.

No plausible mechanism has been proposed to explain either a steady decrease in the mass of the IPK, or an increase in that of its replicas dispersed throughout the world.

[Note 5][29][30][31] Moreover, there are no technical means available to determine whether or not the entire worldwide ensemble of prototypes suffers from even greater long-term trends upwards or downwards because their mass "relative to an invariant of nature is unknown at a level below 1000 μg over a period of 100 or even 50 years".

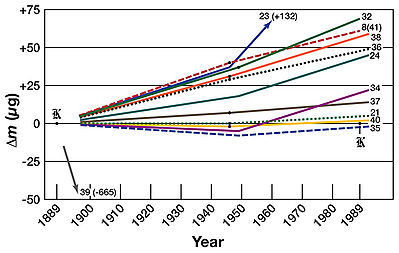

[28] Given the lack of data identifying which of the world's kilogram prototypes has been most stable in absolute terms, it is equally valid to state that the first batch of replicas has, as a group, gained an average of about 25 μg over one hundred years in comparison to the IPK.

The increasing divergence in the masses of the world's prototypes and the short-term instability in the IPK prompted research into improved methods to obtain a smooth surface finish using diamond turning on newly manufactured replicas and was one of the reasons for the redefinition of the kilogram.

Substituting these parameters into Ampère's force law gives: or making the magnitude of the ampere proportional to the square root of the newton and hence of the mass of the IPK.

These dependencies then extend to many chemical, photometric, and electrical units: The SI derived units whose values were not susceptible to changes in the mass of the IPK were either dimensionless quantities, derived entirely from the second, metre, or kelvin, or were defined as the ratio of 2 quantities, both of which were related in the same way to the mass of the IPK, for example: Here the newtons in the numerator and the denominator exactly cancel out when calculating the value of the ohm.

[Note 7] Further, the world's national metrology laboratories must wait for the fourth periodic verification to confirm whether the historical trends persisted.

The same is true with regard to the real-world dependency on the kilogram: if the mass of the IPK was found to have changed slightly, there would be no automatic effect upon the other units of measure because their practical realisations provide an insulating layer of abstraction.

The long-term solution to this problem, however, was to liberate the SI system from its dependency on the IPK by developing a practical realisation of the kilogram that can be reproduced in different laboratories by following a written specification.