I puritani

The offer from the Théâtre came in January 1834; he accepted because "the pay was richer than what I had received in Italy up to then, though only by a little; then because of so magnificent a company; and finally so as to remain in Paris at others' expense.

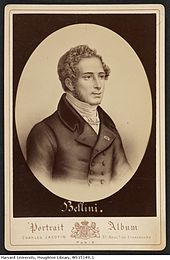

In a word, my dear Florimo, it was an unheard of thing, and since Saturday, Paris has spoken of it in amazement[6]It was to be Bellini's final work; he died in September 1835 at the age of 33.

Upon his arrival in Paris, Bellini quickly entered into the fashionable world of the Parisian salons, including that run by Princess Belgiojoso whom he had met in Milan.

However, on 11 April he is able to say in a letter to Ferlito that he was well and that "I have chosen the story for my Paris opera; it is of the times of Cromvello [Cromwell], after he had King Charles I of England beheaded.

When first shown the play and other possible subjects by Pepoli, in the opinion of writer William Weaver, "it was clearly the heroine's madness that attracted the composer and determined his choice.

"[1] Continuing to work on the yet-unnamed I puritani, Bellini moved from central Paris, and at some time in the late Spring (specific date unknown) Bellini wrote to Pepoli to remind him that he should bring his work with him the following day "so that we can finish discussing the first act, which...will be interesting, magnificent, and proper poetry for music in spite of you and all your absurd rules..."[12] At the same time, he laid out one basic rule for the librettist to follow: Carve into your head in adamantine letters: The opera must draw tears, terrify people, make them die through singing[12]By late June, there had been considerable progress and, in a letter copied into one written to Florimo on 25 July, Bellini writes in reply to Alessandro Lanari [fr], now the director of the Royal Theatres of Naples, telling him that the first act of Puritani is finished and that he expects to complete the opera by September, in order that he may then have time to write a new opera for Naples for the following year.

However, she died exactly a year to the day after the composer, and so this version was not performed on stage until 10 April 1986 at the Teatro Petruzzelli in Bari, with Katia Ricciarelli in the title role.

Given Bellini's own expressions of frustration at working with a new librettist for the first time, one musicologist, Mary Ann Smart, provides a different point of view in regard to Pepoli's approach to writing a libretto.

Pepoli adopts a modern aesthetic agenda, condemning vocal ornamentation as a dilution of dramatic sense and attacking imitation as cheapening music's inherent, nonverbal language.

After touching on exemplary passages from operas by Francesco Morlacchi, Nicola Vaccai, and Vincenzo Bellini, Pepoli turns to the "Marseillaise", arguing that it melds music and poetry perfectly to arouse feeling and provoke action.Quoting Pepoli, Smart continues: "for this song [the "Marseillaise"] the people fight, win, triumph: Europe and the world shouted Liberty!".

When he wrote to Pepoli that his "liberal bent..terrifies me", Bellini's other concern, which proved to be correct, was that words such as libertà would have to be removed if the opera was to be performed in Italy.

Nevertheless, the Suoni la tromba which Bellini described as his "Hymn to Liberty" and which had initially been placed in the opera's first act was enthusiastically received by the composer: "My dear Pepoli, I hasten to express my great satisfaction with the duet I received by post this morning ... the whole is magnificent..."[15] Around the middle of April 1834, Bellini became concerned when he learned that Gaetano Donizetti would be composing for the Théâtre-Italien during the same season as the one for which he was writing.

By September Bellini was writing to Florimo of being able to "polish and re-polish" in the three remaining months before rehearsals and he expresses happiness with Pepoli's verses ("a very beautiful trio for the two basses and La Grisi") and by around mid-December he had submitted the score for Rossini's approval.

Rossini is known to have recommended one change to the placement of the "Hymn to Liberty", which had initially appeared in the first act but which Bellini had already realised could not remain in its written form if the opera was to be given in Italy.

Bellini's ecstatic letter to Florimo which followed the dress rehearsal recounts the enthusiastic reception of many of the numbers throughout the performance, most especially the second act bass duet, so that, by its end: The French had all gone mad; there were such noise and such shouts that they themselves were astonished at being so carried away ...

Herbert Weinstock's chapter on I puritani devotes four pages to details of performances which followed the premiere in Paris, although the Théâtre-Italien gave it over 200 times up to 1909.

Various performances are reported to have taken place in 1921, 1933, 1935, and 1949 in different European cities, but it was not until 1955 in Chicago that Puritani re-appeared in America with Maria Callas and Giuseppe Di Stefano in the major roles.

However, he does include a section on performances from the 19th century forward at the Royal Opera House in London up to Joan Sutherland's 1964 assumption of the role of Elvira.

Scene 1: A fortress near Plymouth, commanded by Lord Gualtiero Valton At daybreak, the Puritan soldiers gather in anticipation of victory over the Royalists.

(Aria, then extended duet: Sai com'arde in petto mio / bella fiamma onnipossente / "You know that my breast burns with overwhelming passion".)

(Aria, Arturo; then Giorgio and Valton; then all assembled: A te, o cara / amore talora / "In you beloved, love led me in secrecy and tears, now it guides me to your side".)

Observed by Arturo and Enrichetta, Elvira appears singing a joyful polonaise (Son vergin vezzosa / "I am a pretty maiden dressed for her wedding"), but she engages the Queen in conversation asking for help with the ringlets of her hair.

As she enters, she expresses all her longing in a mad scene: Elvira, aria: Qui la voce ... Vien, diletto / "Here his sweet voice called me...and then vanished.

Suddenly he hears the sounds of singing coming through the woods: (Elvira, aria: A una fonte afflitto e solo / s'assideva un trovator / "A troubadour sat sad and lonely by a fountain").

Then soldiers' voices are heard close by and Riccardo, Giorgio, and the ladies and gentlemen of the fortress enter announcing Arturo's death sentence.

An ensemble, beginning with Arturo (Credeasi, misera / "Unhappy girl, she believed that I had betrayed her") extends to all assembled, each expressing his or her anguish, with even Riccardo being moved by the plight of the lovers.

Most tenors would typically sing a D-flat instead of an F. However some tenors, like Nicolai Gedda, William Matteuzzi, Gregory Kunde, Lawrence Brownlee, Francesco Demuro and Alasdair Kent, did manage to tackle the challenging high F. In the seldom performed Malibran version, it is Elvira (i.e., the soprano) who sings, in a higher octave, the principal part of Credeasi, misera.

In regard to the impact of the act 2 finale number and its significance in librettist Carlo Pepoli's work as well as in Bellini's music so far, Mary Ann Smart provides one explanation for the power of Suoni la tromba by referring to work of another musicologist, Mark Everist, who, she states "has plausibly suggested that the frenzy was provoked more by the buzzing energy of the two bass voices combined, an unprecedented sonority at the time, than by the duet’s political message".

[23] But, she continues to analyse other aspects of the duet: We should also factor in the force of Pepoli's verses with their promotion of martyrdom and the utter regularity of the music's march-like phrasing, rare in Bellini's ethereal style.

They perform parts of the opera in full costume and sing "A te, o cara" (from act 1, scene 3) as Fitzcarraldo makes his triumphal return to Iquitos.

1976 performance at the Metropolitan Opera