Averroes

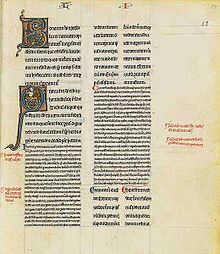

The author of more than 100 books and treatises,[2][3] his philosophical works include numerous commentaries on Aristotle, for which he was known in the Western world as The Commentator and Father of Rationalism.

[4] Averroes was a strong proponent of Aristotelianism; he attempted to restore what he considered the original teachings of Aristotle and opposed the Neoplatonist tendencies of earlier Muslim thinkers, such as Al-Farabi and Avicenna.

In medicine, he proposed a new theory of stroke, described the signs and symptoms of Parkinson's disease for the first time, and might have been the first to identify the retina as the part of the eye responsible for sensing light.

[8] Other forms of the name in European languages include "Ibin-Ros-din", "Filius Rosadis", "Ibn-Rusid", "Ben-Raxid", "Ibn-Ruschod", "Den-Resched", "Aben-Rassad", "Aben-Rasd", "Aben-Rust", "Avenrosdy", "Avenryz", "Adveroys", "Benroist", "Avenroyth" and "Averroysta".

[17] His 13th-century biographer Ibn al-Abbar said he was more interested in the study of law and its principles (usul) than that of hadith and he was especially competent in the field of khilaf (disputes and controversies in the Islamic jurisprudence).

[17][19] In a famous account reported by historian 'Abd al-Wahid al-Marrakushi, the caliph asked Averroes whether the heavens had existed since eternity or had a beginning.

[17] Historian of Islamic philosophy Majid Fakhry also wrote that public pressure from traditional Maliki jurists who were opposed to Averroes played a role.

[17] Averroes was a prolific writer and his works, according to Fakhry, "covered a greater variety of subjects" than those of any of his predecessors in the East, including philosophy, medicine, jurisprudence or legal theory, and linguistics.

[22] The middle commentaries were probably written in response to his patron caliph Abu Yaqub Yusuf's complaints about the difficulty of understanding Aristotle's original texts and to help others in a similar position.

[31] The title of this book is the opposite of al-Juz'iyyat fi al-Tibb ("The Specificities of Medicine"), written by his friend Ibn Zuhr, and the two collaborated intending that their works complement each other.

[33] He also wrote summaries of the works of Greek physician Galen (died c. 210) and a commentary on Avicenna's Urjuzah fi al-Tibb ("Poem on Medicine").

[34] In this work he explains the differences of opinion (ikhtilaf) between the Sunni madhhabs (schools of Islamic jurisprudence) both in practice and in their underlying juristic principles, as well as the reason why they are inevitable.

[34] Other than this surviving text, bibliographical information shows he wrote a summary of Al-Ghazali's On Legal Theory of Muslim Jurisprudence (Al-Mustasfa) and tracts on sacrifices and land tax.

[43] Averroes felt strongly about the incorporation of Greek thought into the Muslim world, and wrote that "if before us someone has inquired into [wisdom], it behooves us to seek help from what he has said.

[60] In the centuries preceding Averroes, there had been a debate between Muslim thinkers questioning whether the world was created at a specific moment in time or whether it has always existed.

[62] He also said the pre-eternity doctrine did not necessarily contradict the Quran and cited verses that mention pre-existing "throne" and "water" in passages related to creation.

[74] Even though all the schools of Islamic law are ultimately rooted in the Quran and hadith, there are "causes that necessitate differences" (al-asbab al-lati awjabat al-ikhtilaf).

[81][82] As did Avempace and Ibn Tufail, Averroes criticizes the Ptolemaic system using philosophical arguments and rejects the use of eccentrics and epicycles to explain the apparent motions of the Moon, the Sun and the planets.

[86] Averroes was aware that Arabic and Andalusian astronomers of his time focused on "mathematical" astronomy, which enabled accurate predictions through calculations but did not provide a detailed physical explanation of how the universe worked.

[50] Rather, he was—in the words of historian of science Ruth Glasner—an "exegetical" scientist who produced new theses about nature through discussions of previous texts, especially the writings of Aristotle.

[92] In his short commentary, the first of the three works, Averroes follows Ibn Bajja's theory that something called the "material intellect" stores specific images that a person encounters.

[95] This theory attracted controversy when Averroes's works entered Christian Europe; in 1229 Thomas Aquinas wrote a detailed critique titled On the Unity of the Intellect against the Averroists.

[107] Averroes's commentaries, which were translated into Latin and entered western Europe in the thirteenth century, provided an expert account of Aristotle's legacy and made them available again.

[112] Paris and Padua were major centers of Latin Averroism, and its prominent thirteenth-century leaders included Siger of Brabant and Boethius of Dacia.

In 1277, at the request of Pope John XXI, Tempier issued another condemnation, this time targeting 219 theses drawn from many sources, mainly the teachings of Aristotle and Averroes.

[117] The Catholic Church's condemnations of 1270 and 1277, and the detailed critique by Aquinas weakened the spread of Averroism in Latin Christendom,[118] though it maintained a following until the sixteenth century, when European thought began to diverge from Aristotelianism.

[120] By this time, there was a cultural renaissance called Al-Nahda ("reawakening") in the Arabic-speaking world and the works of Averroes were seen as inspiration to modernize the Muslim intellectual tradition.

The poem The Divine Comedy by the Italian writer Dante Alighieri, completed in 1320, depicts Averroes, "who made the Great Commentary", along with other non-Christian Greek and Muslim thinkers, in the first circle of hell around Saladin.

[121] Averroes is depicted in Raphael's 1501 fresco The School of Athens that decorates the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican, which features seminal figures of philosophy.

[122][126] The plant genus Averrhoa (whose members include the starfruit and the bilimbi[127]), the lunar crater ibn Rushd,[128] and the asteroid 8318 Averroes are named after him.