Peopling of the Americas

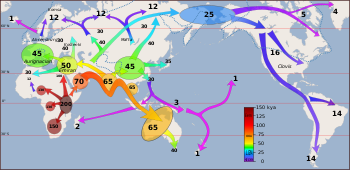

Indigenous peoples of the Americas have been linked to Siberian populations by proposed linguistic factors, the distribution of blood types, and in genetic composition as reflected by molecular data, such as DNA.

[4] The traditional theory is that Ancient Beringians moved when sea levels were significantly lowered due to the Quaternary glaciation,[10][11] following herds of now-extinct Pleistocene megafauna along ice-free corridors that stretched between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets.

While advances in archaeology, Pleistocene geology, physical anthropology, and DNA analysis have progressively shed more light on the subject, significant questions remain unresolved.

[15][18][22][23][24][25] Some new controversial archaeological evidence suggests the possibility that human arrival in the Americas may have occurred prior to the Last Glacial Maximum more than 20,000 years ago.

[18][26][27][28][29][30] Historically, researchers believed a single theory explained the peopling of the Americas, focusing on findings from Blackwater Draw New Mexico, where human artifacts dated from the last ice age were found alongside the remains of extinct animals in 1930s[31] This led to the widespread belief in the "Clovis-first model," proposing that the first Americans migrated over the Beringia land bridge from Asia during a time when glacial passages opened.

[32] Numerous claims of earlier human presence began to challenge the Clovis first model beginning in the 1990s,[33] culminating in significant discoveries at Monte Verde, Chile, dating back 14,500 years.

[38] As research progressed in the 2000s, the narrative shifted from a single migration event to multiple small, diverse groups entering the continent at various points in time.

[47] In New Mexico, researchers uncovered fossilized footprints, dating back perhaps 23,000 years,[48] showing humans and megafauna like mammoths co-existing, which is also under great debate.

[49] In addition, some argue that evidence points towards human presence extending back 130,000 years,[50] though this is outright rejected by the vast majority of scholars across multiple academic fields.

Estimates of the final re-submergence of the Beringian land bridge based purely on present bathymetry of the Bering Strait and eustatic sea level curve place the event around 11,000 years BP (Figure 1).

Ongoing research reconstructing Beringian paleogeography during deglaciation could change that estimate and possible earlier submergence could further constrain models of human migration into North America.

[57] The onset of the Last Glacial Maximum after 30,000 years BP saw the expansion of alpine glaciers and continental ice sheets that blocked migration routes out of Beringia.

[57] The paleoclimates and vegetation of eastern Siberia and Alaska during the Wisconsin glaciation have been deduced from high resolution oxygen isotope data and pollen stratigraphy.

The lowered sea level, and an isostatic bulge equilibrated with the depression beneath the Cordilleran Ice Sheet, exposed the continental shelf to form a coastal plain.

[65] Pollen data indicate mostly herb/shrub tundra vegetation in unglaciated areas, with some boreal forest towards the southern end of the range of Cordilleran ice.

[79][84] The Clovis First theory, which dominated thinking on New World anthropology for much of the 20th century, was challenged in the 2000s by the secure dating of archaeological sites in the Americas to before 13,000 years ago.

[74] Archaeological evidence of pre-Clovis people points to the South Carolina Topper Site being 16,000 years old, at a time when the glacial maximum would have theoretically allowed for lower coastlines.

The study concludes that the ice-free corridor in what is now Alberta and British Columbia "was gradually taken over by a boreal forest dominated by spruce and pine trees" and that the "Clovis people likely came from the south, not the north, perhaps following wild animals such as bison".

[92] Pre-LGM human presence in South America rests partly on the chronology of the controversial Pedra Furada rock shelter in Piauí, Brazil.

If humans managed to breach the continental ice sheets significantly before 13,000 BP, there should be clear evidence for it in the form of at least some stratigraphically discrete archaeological components with a relatively high artifact count.

Unlike other types of fauna that moved between the Americas and Eurasia (mammoths, horses, and lions), Bison survived the North American extinction event that occurred at the end of the Pleistocene.

As nomadic groups, early humans likely followed the food from Eurasia to the Americas – part of the reason why tracing megafaunal DNA is so helpful for garnering insight to these migratory patterns.

[122] However, a third theory, the "Beringian standstill hypothesis", suggests that East Asians instead migrated north to Northeastern Siberia, where they mixed with ANE, and later diverged in Beringia, where distinct Native American lineages formed.

[126] A study published in July 2022 suggested that people in southern China may have contributed to the Native American gene pool, based on the discovery and DNA analysis of 14,000-year-old human fossils.

[132] The conclusions regarding Subhaplogroup D1 indicating potential source populations in the lower Amur[132] and Hokkaido[129] areas stand in contrast to the single-source migration model.

[147][148] Archaeogenetic studies do not support a two-wave model or the Paleoamerican hypothesis of an Australo-Melanesian origin, and firmly assign all Paleo-Indians and modern Native Americans to one ancient population that entered the Americas in a single migration from Beringia.

Arguments based on molecular genetics have in the main, according to the authors, accepted a single migration from Asia with a probable pause in Beringia, plus later bi-directional gene flow.

[156] Geological findings on the timing of the ice-free corridor also challenge the notion that Clovis and pre-Clovis human occupation of the Americas was a result of migration through that route following the Last Glacial Maximum.

Cosmogenic exposure dating, a technique that analyzes when in Earth's history a landscape was exposed to cosmic rays (and therefore unglaciated), performed by Mark Swisher suggests that an older ice-free corridor existed in North America 25,000 years ago.

Once the coastlines of Alaska and British Columbia had deglaciated about 16,000 years ago, these kelp forest (along with estuarine, mangrove, and coral reef) habitats would have provided an ecologically homogenous migration corridor, entirely at sea level, and essentially unobstructed.

!["Maps depicting each phase of the three-step early human migrations for the peopling of the Americas. (A) Gradual population expansion of the Amerind ancestors from their Central East Asian gene pool (blue arrow). (B) Proto-Amerind occupation of Beringia with little to no population growth for ≈20,000 years. (C) Rapid colonization of the New World by a founder group migrating southward through the ice-free, inland corridor between the eastern Laurentide and western Cordilleran Ice Sheets (green arrow) and/or along the Pacific coast (red arrow). In (B), the exposed seafloor is shown at its greatest extent during the last glacial maximum at ≈20–18,000 years ago [25]. In (A) and (C), the exposed seafloor is depicted at ≈40,000 years ago and ≈16,0000 years ago, when prehistoric sea levels were comparable. A scaled-down version of Beringia today (60% reduction of A–C) is presented in the lower left corner. This smaller map highlights the Bering Strait that has geographically separated the New World from Asia since ≈11–10,000 years ago."](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d7/Journal.pone.0001596.g004.png/280px-Journal.pone.0001596.g004.png)