Spanish conquest of Guatemala

[2] The first contact between the Maya and European explorers came in the early 16th century when a Spanish ship sailing from Panama to Santo Domingo (Hispaniola) was wrecked on the east coast of the Yucatán Peninsula in 1511.

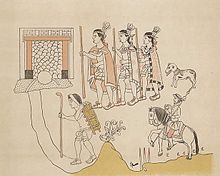

[4] Pedro de Alvarado arrived in Guatemala from the newly conquered Mexico in early 1524, commanding a mixed force of Spanish conquistadors and native allies, mostly from Tlaxcala and Cholula.

[34] In the centuries preceding the arrival of the Spanish the Kʼicheʼ had carved out a small empire covering a large part of the western Guatemalan Highlands and the neighbouring Pacific coastal plain.

[42] The Spanish described the weapons of war of the Petén Maya as bows and arrows, fire-sharpened poles, flint-headed spears and two-handed swords crafted from strong wood with the blade fashioned from inset obsidian,[43] similar to the Aztec macuahuitl.

[nb 2] The conquistadors were all volunteers, the majority of whom did not receive a fixed salary but instead a portion of the spoils of victory, in the form of precious metals, land grants and provision of native labour.

[51] Bernal Díaz del Castillo was a petty nobleman who accompanied Hernán Cortés when he crossed the northern lowlands, and Pedro de Alvarado on his invasion of the highlands.

[74] In 1522 Cortés sent Mexican allies to scout the Soconusco region of lowland Chiapas, where they met new delegations from Iximche and Qʼumarkaj at Tuxpán;[75] both of the powerful highland Maya kingdoms declared their loyalty to the king of Spain.

Cortés decided to despatch Pedro de Alvarado with 180 cavalry, 300 infantry, crossbows, muskets, 4 cannons, large amounts of ammunition and gunpowder, and thousands of allied Mexican warriors from Tlaxcala, Cholula and other cities in central Mexico;[76] they arrived in Soconusco in 1523.

[88] This battle exhausted the Kʼicheʼ militarily and they asked for peace and offered tribute, inviting Pedro de Alvarado into their capital Qʼumarkaj, which was known as Tecpan Utatlan to the Nahuatl-speaking allies of the Spanish.

[112] Two years later, on 9 February 1526, a group of sixteen Spanish deserters burnt the palace of the Ahpo Xahil, sacked the temples and kidnapped a priest, acts that the Kaqchikel blamed on Pedro de Alvarado.

[114][nb 5] Conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo recounted how in 1526 he returned to Iximche and spent the night in the "old city of Guatemala" together with Luis Marín and other members of Hernán Cortés's expedition to Honduras.

[117] The Spanish abandoned Tecpán in 1527, because of the continuous Kaqchikel attacks, and moved to the Almolonga Valley to the east, refounding their capital on the site of today's San Miguel Escobar district of Ciudad Vieja, near Antigua Guatemala.

As Alvarado dug in and laid siege to the fortress, an army of approximately 8,000 Mam warriors descended on Zaculeu from the Cuchumatanes mountains to the north, drawn from those towns allied with the city.

[134] Armed with the knowledge gained from their prisoners, Alvarado sent 40 men to cover the exit from the cave and launched another assault along the ravine from the west, in single file owing to its narrowness, with crossbowmen alternating with soldiers bearing muskets, each with a companion sheltering him from arrows and stones with a shield.

[154] In 1684, a council led by Enrique Enríquez de Guzmán, the governor of Guatemala, decided on the reduction of San Mateo Ixtatán and nearby Santa Eulalia, both within the colonial administrative district of the Corregimiento of Huehuetenango.

[157] To prevent news of the Spanish advance reaching the inhabitants of the Lacandon area, the governor ordered the capture of three of San Mateo's community leaders, named as Cristóbal Domingo, Alonso Delgado and Gaspar Jorge, and had them sent under guard to be imprisoned in Huehuetenango.

[101] On 8 May 1524, soon after his arrival in Iximche and immediately following his subsequent conquest of the Tzʼutujil around Lake Atitlán, Pedro de Alvarado continued southwards to the Pacific coastal plain with an army numbering approximately 6,000,[nb 8] where he defeated the Pipil of Panacal or Panacaltepeque (called Panatacat in the Annals of the Kaqchikels) near Izcuintepeque on 9 May.

However, Pedro de Alvarado pressed ahead and when the Spanish entered the town the defenders were completely unprepared, with the Pipil warriors indoors sheltering from the torrential rain.

[174] Jorge de Alvarado led the first attempt with thirty to forty cavalry and although they routed the enemy they were unable to retrieve any of the lost baggage, much of which had been destroyed by the Xinca for use as trophies.

Pedro de Portocarrero led the second attempt with a large infantry detachment but was unable to engage with the enemy due to the difficult Kʼicheʼ kingdom of Qʼumarkaj terrain, so returned to Nancintla.

[182] Cortés accepted an invitation from Aj Kan Ekʼ, the king of the Itza, to visit Nojpetén (also known as Tayasal), and crossed to the Maya city with 20 Spanish soldiers while the rest of his army continued around the lake to meet him on the south shore.

When he came to a river swollen with the constant torrential rains that had been falling during the expedition, Cortés turned upstream to the Gracias a Dios rapids, which took two days to cross and cost him more horses.

This strategy resulted in the gradual depopulation of the forest, simultaneously converting it into a wilderness refuge for those fleeing Spanish domination, both for individual refugees and for entire communities, especially those congregaciones that were remote from centres of colonial authority.

[197] Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas arrived in the colony of Guatemala in 1537 and immediately campaigned to replace violent military conquest with peaceful missionary work.

[191] Because it had not been possible to conquer the land by military means, the governor of Guatemala, Alonso de Maldonado, agreed to sign a contract promising he would not establish any new encomiendas in the area should Las Casas' strategy succeed.

one could make a whole book ... out of the atrocities, barbarities, murders, clearances, ravages and other foul injustices perpetrated ... by those that went to Guatemala In this way they congregated a group of Christian Indians in the location of what is now the town of Rabinal.

[191] In 1543 the new colonial reducción of Santo Domingo de Cobán was founded at Chi Monʼa to house the relocated Qʼeqchiʼ from Chichen, Xucaneb and Al Run Tax Aj.

Santo Tomás Apóstol was founded nearby the same year at Chi Nim Xol, it was used in 1560 as a reducción to resettle Chʼol communities from Topiltepeque and Lacandon in the Usumacinta Valley.

[224] Martín de Ursúa y Arizmendi arrived on the western shore of Lake Petén Itzá with his soldiers on 26 February 1697 and, once there, built a galeota, a large and heavily armed oar-powered attack boat.

With Nojpetén safely in the hands of the Spanish, Ursúa returned to Campeche; he left a small garrison on the island, isolated amongst the hostile Itza and Kowoj who still dominated the mainland.