Mesoamerican writing systems

These surviving texts give anthropologists and historians valuable insight into the origins of Mesoamerican languages, culture, religion, and government.

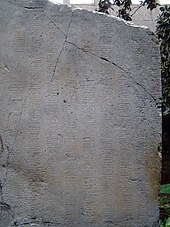

This block was discovered by locals in the Olmec heartland and was dated by the archaeologists to approximately 900 BCE based on other debris.

Rising in the late Pre-Classic era after the decline of the Olmec civilization, the Zapotecs of present-day Oaxaca built an empire around Monte Albán.

A small number of artifacts found in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec show examples of another early Mesoamerican writing system.

The following year, however, their interpretation was disputed by Stephen Houston and Michael D. Coe, who unsuccessfully applied Justeson and Kaufman's decipherment system against epi-Olmec script from the back of a hitherto unknown mask.

In the highland Maya archaeological sites of Abaj Takalik and Kaminaljuyú writing has been found dating to Izapa culture.

Early examples include the painted inscriptions at the caves of Naj Tunich and La Cobanerita in El Petén, Guatemala.

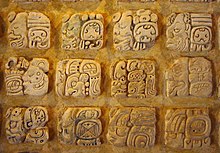

The Maya script is generally considered to be the most fully developed Mesoamerican writing system, mostly because of its extraordinary aesthetics and because it has been partially deciphered.

The Chiapa de Corzo cylinder seal found at that location in Mexico also appears to be an example of an unknown Mesoamerican script.

[6] Certain iconographic elements in Teotihuacano art have been considered as a potential script,[7] although it is attested sparsely and in individual glyphs rather than texts.

The Mixtec writing system consisted of a set of figurative signs and symbols that served as guides for storytellers as they recounted legends.

[9] Mixtec writing has been preserved through various archaeological artifacts that have survived the passage of time and the destruction of the Spanish conquest.

[11] Most of the current knowledge about the writing of the Mixtecans is due to the work of Alfonso Caso, who undertook the task of deciphering the code based on a set of pre-Columbian and colonial documents of the Mixtec culture.

[12] Although the Mixtecs had a set of symbols that allowed them to record historical dates, they did not use the long count calendar characteristic of other southeast Mesoamerican writing systems.

When Europeans arrived in the 16th century, they found several writing systems in use that drew from Olmec, Zapotec, and Teotihuacano traditions.

Archaeologists have found inside elite Mayan homes personal objects inscribed with the owners' names.

As European Franciscan missionaries arrived they found that the Cholutecans used the rebus principle as a way to translate information into Latin as a teaching aid for the natives to learn Christian prayers.

[18] The Florentine Codex, compiled 1545–1590 by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún includes a history of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire from the Mexica viewpoint,[19] with bilingual Nahuatl/Spanish alphabetic text and illustrations by native artists.

[20] There are also the works of Dominican Diego Durán (before 1581), who drew on indigenous pictorials and living informants to create illustrated texts on history and religion.

[22] For writing Maya, colonial manuscripts conventionally adopt a number of special characters and diacritics thought to have been invented by Francisco de la Parra around 1545.