Ice trade

Over the coming years the trade widened to Cuba and Southern United States, with other merchants joining Tudor in harvesting and shipping ice from New England.

Despite a temporary increase in production in the U.S. during the war, the interwar years saw further developments (especially the widespread adoption of mechanical refrigerators at the domestic level) which caused the total collapse of the international ice trade.

In the Mediterranean and in South America, for example, there was a long history of collecting ice from the upper slopes of the Alps and the Andes during the summer months and transporting this down into the cities.

[7] Porous clay pots containing boiled, cooled water were laid out on top of straw in shallow trenches; under favourable circumstances, thin ice would form on the surface during winter nights which could be harvested and combined for sale.

[8] There were production sites at Hugli-Chuchura and Allahabad, but this "hoogly ice" was only available in limited amounts and considered of poor quality because it often resembled soft slush rather than hard crystals.

[10] In Europe, various chemical means for cooling drinks were created by the 19th century; these typically used sulphuric acid to chill the liquid, but were not capable of producing actual ice.

[13] Nonetheless, icehouses were relatively common amongst the wealthier members of society by 1800, filled with ice cut, or harvested, from the frozen surface of ponds and streams on their local estates during the winter months.

[15] Some ships occasionally transported ice from New York and Philadelphia for sale to the southern U.S. states, in particular Charleston in South Carolina, laying it down as ballast on the trip.

[19] The first shipments took place in 1806 when Tudor transported an initial trial cargo of ice, probably harvested from his family estate at Rockwood, to the Caribbean island of Martinique.

[21] The 1812 war briefly disrupted trade, but over subsequent years Tudor began to export fruit back from Havana to the mainland on the return journey, kept fresh with part of the unsold ice cargo.

[27] At these lower prices, ice began to sell in considerable volumes, with the market moving beyond the wealthy elite to a wider range of consumers, to the point where supplies became overstretched.

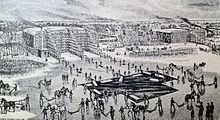

The first and most profitable of these new routes was to India: in 1833 Tudor combined with the businessmen Samuel Austin and William Rogers to attempt to export ice to Calcutta using the brigantine ship the Tuscany.

[34] The Anglo-Indian elite, concerned about the effects of the summer heat, quickly agreed to exempt the imports from the usual East India Company regulations and trade tariffs, and the initial net shipment of around a hundred tons (90,000 kg) sold successfully.

[35] With the ice selling for three pence (£0.80 in 2010) per pound (0.45 kg), the first shipment aboard the Tuscany produced profits of $9,900 ($253,000), and in 1835 Tudor commenced regular exports to Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay.

[43] The export of chilled vegetables, fish, butter, and eggs to the Caribbean and to markets in the Pacific grew during the 1840s, with as many as 35 barrels being transported on a single ship, alongside a cargo of ice.

[49] After some initial success, the venture eventually failed, in part because the English chose not to adopt chilled drinks in the same way as North Americans, but also because of the long distances involved in the trade and the consequent costs of ice wastage through melting.

[76] Australia's distance from New England, where journeys could take 115 days, and the consequent high level of wastage – 150 tons of the first 400-ton shipment to Sydney melted en route – made it relatively easy for plant ice to compete with the natural product.

[94] In the post-war years, the number of such plants increased, but once competition from the North recommenced, cheaper natural ice initially made it hard for the manufacturers to make a profit.

Carl von Linde found ways of applying mechanical refrigeration to the brewing industry, removing its reliance on natural ice; cold warehouses and meat packers began to rely on chilling plants.

[112] Despite this emerging competition, natural ice remained vital to North American and European economies, with demand driven up by rising living standards.

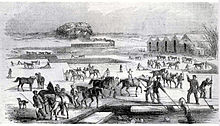

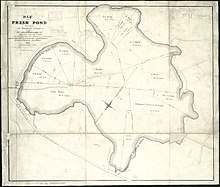

[149] In order for natural ice to reach its customers, it had to be harvested from ponds and rivers, then transported and stored at various sites before finally being used in domestic or commercial applications.

[156] Low-lying, boggy land was dammed and flooded in Maine towards the end of the century to meet surge demands, while pre-existing artificial mill ponds in Wisconsin turned out to be ideal for harvesting commercial ice.

[157] In Alaska, a large, shallow artificial lake covering around 40 acres (16 hectares) was produced in order to assist in ice production and harvesting; similar approaches were taken in the Aleutian islands; in Norway this was taken further, with a number of artificial lakes up to half a mile long built on farmland to increase supplies, including some built out into the sea to collect fresh water for ice.

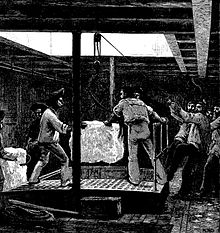

[174] The uniform blocks that Wyeth's process produced also made it possible to pack more ice into the limited space of a ship's hold, and significantly reduced the losses from melting.

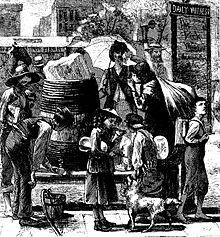

[194] By the 1870s, various specialist distributors existed in the major cities, with local fuel dealers or other businesses selling and delivering ice in the smaller communities.

Iced drinks were a novelty and were initially viewed with concern by customers, worried about the health risks, although this rapidly vanished in the U.S.[214] By the mid-19th century, water was always chilled in America if possible.

[225] Although using ice to chill foods was relatively simple, it required considerable experimentation to produce efficient and reliable methods for controlling the flow of warm and cold air in different containers and transport systems.

[226] Early approaches to preserving food used variants of traditional cold boxes to solve the problem of how to take small quantities of products short distances to market.

Thomas Moore, an engineer from Maryland, invented an early refrigerator which he patented in 1803; this involved a large, insulated wooden box, with a tin container of ice embedded in the top.

[236] The ice trade enabled its widespread use in medicine in attempts to treat diseases and to alleviate their symptoms, as well as making tropical hospitals more bearable.