Snowball Earth

Proponents of the hypothesis argue that it best explains sedimentary deposits that are generally believed to be of glacial origin at tropical palaeolatitudes and other enigmatic features in the geological record.

Opponents of the hypothesis contest the geological evidence for global glaciation and the geophysical feasibility of an ice- or slush-covered ocean,[3][4] and they emphasize the difficulty of escaping an all-frozen condition.

[6] Douglas Mawson, an Australian geologist and Antarctic explorer, spent much of his career studying the stratigraphy of the Neoproterozoic in South Australia, where he identified thick and extensive glacial sediments.

[7] Mawson's ideas of global glaciation, however, were based on the mistaken assumption that the geographic position of Australia, and those of other continents where low-latitude glacial deposits are found, have remained constant through time.

[citation needed] With the advancement of the continental drift hypothesis, and eventually plate tectonic theory, came an easier explanation for the glaciogenic sediments—they were deposited at a time when the continents were at higher latitudes.

In 1964, the idea of global-scale glaciation reemerged when W. Brian Harland published a paper in which he presented palaeomagnetic data showing that glacial tillites in Svalbard and Greenland were deposited at tropical latitudes.

[11] The major contributions from this work were: (1) the recognition that the presence of banded iron formations is consistent with such a global glacial episode, and (2) the introduction of a mechanism by which to escape from a completely ice-covered Earth—specifically, the accumulation of CO2 from volcanic outgassing leading to an ultra-greenhouse effect.

His studies of phosphorus deposits and banded iron formations in sedimentary rocks made him an early adherent of the snowball Earth hypothesis postulating that the planet's surface froze more than 650 Ma.

[12] Interest in the notion of a snowball Earth increased dramatically after Paul F. Hoffman and his co-workers applied Kirschvink's ideas to a succession of Neoproterozoic sedimentary rocks in Namibia and elaborated upon the hypothesis in the journal Science in 1998 by incorporating such observations as the occurrence of cap carbonates.

[13] In 2010, Francis A. Macdonald, assistant professor at Harvard in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, and others, reported evidence that Rodinia was at equatorial latitude during the Cryogenian period with glacial ice at or below sea level, and that the associated Sturtian glaciation was global.

Long before the advent of the snowball Earth hypothesis, many Neoproterozoic sediments had been interpreted as having a glacial origin, including some apparently at tropical latitudes at the time of their deposition.

Further, sedimentary features that could only form in open water (for example: wave-formed ripples, far-traveled ice-rafted debris and indicators of photosynthetic activity) can be found throughout sediments dating from the snowball-Earth periods.

The emplacement of several large igneous provinces shortly before the Cryogenian and the subsequent chemical weathering of the enormous continental flood basalts created by them, aided by the breakup of Rodinia that exposed many of these flood basalts to warmer, moister conditions closer to the coast and accelerated chemical weathering, is also believed to have caused a major positive shift in carbon isotopic ratios and contributed to the beginning of the Sturtian glaciation.

Being isolated from the oceans, such lakes could have been stagnant and anoxic at depth, much like today's Black Sea; a sufficient input of iron could provide the necessary conditions for BIF formation.

[44] The formation of such sedimentary rocks could be caused by a large influx of positively charged ions, as would be produced by rapid weathering during the extreme greenhouse following a snowball Earth event.

[53] Global warming associated with large accumulations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere over millions of years, emitted primarily by volcanic activity, is the proposed trigger for melting a snowball Earth.

[60] The start of snowball Earths are marked by a sharp downturn in the δ13C value of sediments,[61] a hallmark that may be attributed to a crash in biological productivity as a result of the cold temperatures and ice-covered oceans.

In January 2016, Gernon et al. proposed a "shallow-ridge hypothesis" involving the breakup of Rodinia, linking the eruption and rapid alteration of hyaloclastites along shallow ridges to massive increases in alkalinity in an ocean with thick ice cover.

Gernon et al. demonstrated that the increase in alkalinity over the course of glaciation is sufficient to explain the thickness of cap carbonates formed in the aftermath of Snowball Earth events.

The resulting sediments supplied to the ocean would be high in nutrients such as phosphorus, which combined with the abundance of CO2 would trigger a cyanobacteria population explosion, which would cause a relatively rapid reoxygenation of the atmosphere and may have contributed to the rise of the Ediacaran biota and the subsequent Cambrian explosion—a higher oxygen concentration allowing large multicellular lifeforms to develop.

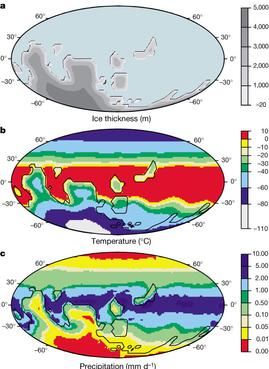

[74] While the presence of glaciers is not disputed, the idea that the entire planet was covered in ice is more contentious, leading some scientists to posit a "slushball Earth", in which a band of ice-free, or ice-thin, waters remains around the equator, allowing for a continued hydrologic cycle.

Attempts to construct computer models of a snowball Earth have struggled to accommodate global ice cover without fundamental changes in the laws and constants which govern the planet.

[50] A longer record from Oman, constrained to 13°N, covers the period from 712 to 545 million years ago—a time span containing the Sturtian and Marinoan glaciations—and shows both glacial and ice-free deposition.

[81] Strontium isotopic data have been found to be at odds with proposed snowball Earth models of silicate weathering shutdown during glaciation and rapid rates immediately post-glaciation.

Such seas can experience a wide range of chemistries; high rates of evaporation could concentrate iron ions, and a periodic lack of circulation could allow anoxic bottom water to form.

This rifting, and associated subsidence, would produce the space for the fast deposition of sediments, negating the need for an immense and rapid melting to raise the global sea levels.

[88] Proponents counter that it may have been possible for life to survive in these ways: However, organisms and ecosystems, as far as it can be determined by the fossil record, do not appear to have undergone the significant change that would be expected by a mass extinction.

As the solar irradiance was notably weaker at the time, Earth's climate may have relied on methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, to maintain surface temperatures above freezing.

The status of the Kaigas "glaciation" or "cooling event" is currently unclear; some scientists do not recognise it as a glacial, others suspect that it may reflect poorly dated strata of Sturtian association, and others believe it may indeed be a third ice age.

Hypothetical runaway greenhouse state Tropical temperatures may reach poles Global climate during an ice age Earth's surface entirely or nearly frozen over