Icelandic language

While most of them have greatly reduced levels of inflection (particularly noun declension), Icelandic retains a four-case synthetic grammar (comparable to German, though considerably more conservative and synthetic) and is distinguished by a wide assortment of irregular declensions.

Since 1995, on 16 November each year, the birthday of 19th-century poet Jónas Hallgrímsson is celebrated as Icelandic Language Day.

In addition, women from Norse Ireland, Orkney, or Shetland often married native Scandinavian men before settling in the Faroe Islands and Iceland.

Though more archaic than the other living Germanic languages, Icelandic changed markedly in pronunciation from the 12th to the 16th century, especially in vowels (in particular, á, æ, au, and y/ý).

The modern Icelandic alphabet has developed from a standard established in the 19th century, primarily by the Danish linguist Rasmus Rask.

The later Rasmus Rask standard was a re-creation of the old treatise, with some changes to fit concurrent Germanic conventions, such as the exclusive use of k rather than c. Various archaic features, such as the letter ð, had not been used much in later centuries.

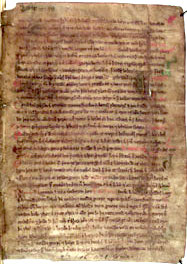

[13] Modern speakers can understand the original sagas and Eddas which were written about eight hundred years ago.

The sagas are usually read with updated modern spelling and footnotes, but otherwise are intact (as with recent English editions of Shakespeare's works).

The convention covers visits to hospitals, job centres, the police, and social security offices.

[18] The Nordic countries have committed to providing services in various languages to each other's citizens, but this does not amount to any absolute rights being granted, except as regards criminal and court matters.

[29] Icelandic retains many grammatical features of other ancient Germanic languages, and resembles Old Norwegian before much of its fusional inflection was lost.

Modern Icelandic is still a heavily inflected language with four cases: nominative, accusative, dative and genitive.

For example, within the strong masculine nouns, there is a subclass (class 1) that declines with -s (hests) in the genitive singular and -ar (hestar) in the nominative plural.

However, there is another subclass (class 3) of strong masculine nouns that always declines with -ar (hlutar) in the genitive singular and -ir (hlutir) in the nominative plural.

Examples are koma ("come") vs. komast ("get there"), drepa ("kill") vs. drepast ("perish ignominiously") and taka ("take") vs. takast ("manage to").

Icelandic personal names are patronymic (and sometimes matronymic) in that they reflect the immediate father or mother of the child and not the historic family lineage.

The bishop Oddur Einarsson wrote in 1589 that the language has remained unspoiled since the time the ancient literature of Iceland was written.

[41] In the early 19th century, due to the influence of romanticism, importance was put on the purity of spoken language as well.

[42] The changes brought by the purism movement have had the most influence on the written language, as many speakers use foreign words freely in speech but try to avoid them in writing.

[43] There is still a conscious effort to create new words, especially for science and technology, with many societies publishing dictionaries, some with the help of The Icelandic Language Committee (Íslensk málnefnd).