Idolatry in Sikhism

Sikhism prohibits idolatry,[1] in accordance with mainstream Khalsa norms and the teachings of the Sikh Gurus,[2] a position that has been accepted as orthodox.

[3][4][5] Growing Sikh popular discontent with Gurdwara administration and practices during the 1800s,[6][7][5] revivalist movements in the mid-1800s who opposed idol worship like the Nirankaris[7] and the Namdharis[8] (who however have followed a living guru since its inception), and the encroachment of Brahmanical customs in the Golden Temple during that period,[5][2][9] led to the establishment of the Singh Sabha Movement in 1873, in which the Tat Khalsa faction, dominant since the early 1880s, pushed to renew and standardize the practice of Sikhism.

After a period of political advancement, the Khalsa faction re-established direct control over Gurdwara management[10] over the Udasi and Hindu[9] mahants, who institutionalized idol worship[5] and would eventually identify with the Sanatan Sikhs, who identified with the Brahmanical social structure[11] and considered idol worship as not harmful.

The Dasam Granth includes idolatry along with other practices such as smearing sandal paste, offering food, visiting graves and tombs, bowing and others as futile and unhelpful in knowing God.

[20] According to the Indologist Harold Coward, the Sikh scriptures critique idolatry and Guru Nanak's words protest and condemn empty, magical worship of idols.

[39][40][36] The Dabistan also states, "Nanak praised the religion of the Muselmans, as well as the avatars and divinities of the Hindus; but he knew that these objects of veneration were created and not creators, and he denied their real descent from heaven, and their union with mankind,"[41][42] described by the author as the doctrines of halool and ittehad.

[47] The British colonial rulers, after annexing the Sikh Empire in mid-19th-century, continue to patronize and gift land grants to these mahants, thereby increasing their strength.

[2] This remained the case during the time of the Gurus, until increased Mughal persecution in the eighteenth century[12][13] forced the Khalsa to yield gurdwara control to mahants, or custodians, who often belonged to Udasi, Nirmala, or other Brahmanical-influenced ascetic heterodox sects,[51] or were non-Sikh altogether.

[13] This created the opportunity for other less disruptive sects to gain control of Sikh institutions,[51] due to their lack of external identifying features compared to the initiated Khalsa.

[54] The Singh Sabha movement eventually brought the Khalsa back to the fore of Gurdwara administration, which they achieved after expelling the mahants and their corrupt practices, which included idolatry,[6] financial malfeasance, Brahmanical privilege, and the dissemination of unsavory literature.

[60] According to Mandair, the Sikh scripture includes words such as "murat", "sarir" and "akal,” which, selectively read, can be viewed as teaching an abstract "formless" concept of God.

However, states Mandair, other parts of the Sikh scripture include terms such as "murat" which relate to "form, shape" creating exegetical difficulty.

[61] Mandair posits that Khalsa writers of the Singh Sabha movement reinterpreted and gave new contextual meanings to the words such as "murat" in order to show that there is no inconsistency and contradiction in their exegetical attempts around idolatry in Sikhism.

[61] In response, historian and professor Gurdarshan Singh Dhillon calls Mandair’s own reading of the text “selective,” and as seeking "to make Guru Nanak’s monotheism redundant.” Dhillon sees Mandair's view as ignoring Guru Nanak’s own direct words regarding idolatry, and questions how qualities listed in the Mul Mantar could apply to an idol, “as the term “Akal Murat” takes its meaning not in isolation but from the total understanding of the Mul Mantar.”[62] and that the terms “timeless,” and “Eternal Reality” cannot be applied to a physical idol.

Mandair’s purpose is described as an effort “to connect Guru Nanak’s Time and World and then to idolatry, “tear[ing] words and terms out of context and twists their meaning to suit his contrived thesis.”[62] Dhillon holds that Mandair’s inclination towards the McLeodian school of Sikh thought led to utilizing the Hegelian approach to produce ‘new knowledge formations’ to delegitimize Sikh interpretations of their own faith in order to serve “Hindu-centric and Christian-centric state models” by levelling regional identities in an attempt to overcome identity politics bolstered by the concepts of religion and regional political sovereignty.

[62] Among the earliest reform movements that strongly opposed idol worship practices in the Sikh community was the Nirankari sect started by Baba Dyal Das (1783–1855).

[63][64] The Nirankaris condemned the growing idol worship, obeisance to living gurus and influence of Brahmanic ritual that had crept into the Sikh Panth.

[63] He built a new Gurdwara in Rawalpindi (now in Pakistan), Dyal Das was opposed for his strict teachings by upper-caste Sikhs and had to shift his residence several times,[7] eventually moving his reform movement into its suburbs.

[7] However, when they and an offshoot called the Sant Nirankari Mission eventually reverted[7] to treating their leaders as living gurus or gods[66] they came into conflict with mainstream Sikhs, especially in the late 1970s.

[64][67][68] According to Jacob Copeman, Nirankaris revere Guru Nanak, but they also worship a living saint (satguru) as god.

[8] The Namdharis had more of a social impact due to the fact that they emphasized Khalsa identity and the authority of the Guru Granth Sahib.

"Eternal Sikh,"[74] a term and formulation coined by Harjot Oberoi[46]) were most prominent in the 1800s and identified with the Brahmanical social structure and caste system, and self-identified as Hindu.

[80][10] According to Tony Ballantyne, the Sanatan Sikhs were spiritually sympathetic to the worship of idols and images, rural traditions and to respecting Hindu scriptures.

[81] Scholars such as Eleanor Nesbitt state the Nanaksar Gurdwaras practice of offering food cooked by Sikh devotees to the Guru Granth Sahib, as well as curtaining the scripture during this ritual, as a form of idolatry.

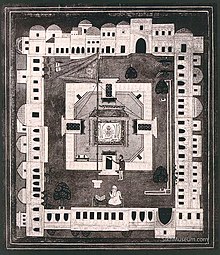

[82] The daily routine of the gurdwara includes the prakash, which involves carrying the Sikh scripture, the Guru Granth Sahib, in a small procession of granthis, or gurdwara religious officials, placing it on a stand, unwrapping it, and opening it to be read; and the sukhasan, when the scripture is retired at the end of the day to a designated room, or sachkhand.

[83] English travellers to Sikh temples during the early 1900s saw the veneration of the Granth as coming close to defeating the purpose of Guru Nanak's reforms (away from external authority to living experience), and saw it as a warning to Christian Protestants to avoid lapsing into bibliolatry, as Hindu temple idol worship served as a warning to Catholics.

Like Hindus who he called as "degenerate, idolatrous", he criticized the Sikhs for worshipping the Guru Granth Sahib scripture as an idol like a mithya (false icon).

It moulds "meanings, values and ideologies" and creates a framework for congregational worship, states Myrvold, that is found in all major faiths.