Illegalism

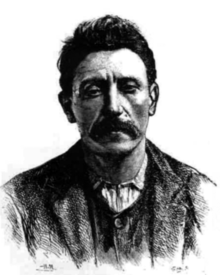

Some anarchists, like Clément Duval and Marius Jacob, justified theft with theories of individual reclamation (la reprise individuelle) and propaganda of the deed and saw their crime as an educational and organizational tool to facilitate a broader resistance movement.

They argued that their actions required no moral basis and illegal acts were taken not in the name of a higher ideal, but in pursuit of one's own desires.

Illegalists contend that both written law and standards of morality perpetuate and reproduce capitalist thought, which they find oppressive and exploitative.

[5] The revolutionary nature of the work did, however, necessitate a distinct social organization which promoted close communicative bonds between illegalists.

[6] Its praxis largely involves direct intervention in economic affairs and seeks to subvert authoritarian, capitalist structures by reappropriating wealth through illegal acts such as theft, counterfeiting, swindling, and robbery.

[6] Though both self-interest and political organizing played a role in the ideology of all illegalists, they were motivated by these respective factors to varying degrees.

Participants viewed the movement differently, roughly along the lines of the distinction between those who ascribed to notions of "individual reappropriation" and "propaganda by the deed" and those who did not.

They committed crimes in hopes that they would be exemplary of revolutionary tactics and serve as educational tools in organizing a broader resistance movement.

They saw their crime as influential in the way that it might subvert moral codes enforced by an unjust system and participated in illegalism in hopes of generating tangible structural change.

With the help of a couple anarchist affiliates, Jacob then impersonated a senior police officer in a staged pawnshop raid in Marseilles in May 1899.

During the onset of the 20th century, he organized a group of anarchist illegalists who shared his experience of alienation from the world of traditional work.

Individuals in the group assumed different roles which would work together cooperatively to effectively and efficiently carry out crime: the scouts, the burglars, and the fencers.

This way, there were people responsible for observing and documenting potential sites for seamless crime, others who executed the robbery swiftly with the adequate tools at their disposal, and more who managed the resale of acquired goods, respectively.

Members were armed, but murder was only condoned in the event of necessary self defense and they prioritized escape tactics to reduce the potential for such interpersonal conflict.

Jacob was sentenced to lifelong manual labor in the penal colonies, alongside his affiliate Bour, who killed the police officer who caught them in Abbeville.

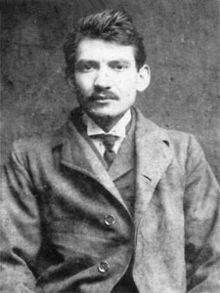

Composed of individuals who identified with the emerging illegalist milieu, the gang utilized cutting-edge technology (including automobiles and repeating rifles) not yet available to the French police.

The group originated in Belgium, a location conducive to the congregation of political exiles and young men who wanted to escape obligation to serve in the French military.

During his time in the workforce, he was increasingly disillusioned to the practicality of radical economic change, dissatisfied even by the work of union leaders, who he considered as exploitative as the capitalists.

Another paper, l'Anarchie, included an article by Victor Kibalchich, which expressed the following sentiment: "In the ordinary sense of the word we cannot and will not be honest.

He was also roughly 10 years older than the rest of the group, which was advantageous in that it gave him a distinct confidence and infectious measured recklessness.

[5] The Bonnot Gang committed its first robbery at a bank in Paris in December 1911, during which they shot a collection clerk, stole over 5,000 francs, and escaped in a stolen vehicle.

[6] For example, following his arrest for harboring members of the Bonnot Gang, Victor Serge, once a forceful defender of illegalism, became a sharp critic.

The legal consequences of their actions prompted a sense that their work was not worthwhile, as attempts towards self liberation and political influence involved the risk of being denied all freedom and capacity to organize meaningfully.