Immunization

When this system is exposed to molecules that are foreign to the body, called non-self, it will orchestrate an immune response, and it will also develop the ability to quickly respond to a subsequent encounter because of immunological memory.

Therefore, by exposing a human, or an animal, to an immunogen in a controlled way, its body can learn to protect itself: this is called active immunization.

Natural immunity can have degrees of effectiveness (partial rather than absolute) and may fade over time (within months, years, or decades, depending on the pathogen).

Vaccines against microorganisms that cause diseases can prepare the body's immune system, thus helping to fight or prevent an infection.

The first clear reference to smallpox inoculation was made by the Chinese author Wan Quan (1499–1582) in his Douzhen xinfa (痘疹心法) published in 1549.

[5] It was introduced into England from Turkey by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu in 1721 and used by Zabdiel Boylston in Boston the same year.

Until the 1880s vaccine/vaccination referred only to smallpox, but Louis Pasteur developed immunization methods for chicken cholera and anthrax in animals and for human rabies, and suggested that the terms vaccine/vaccination should be extended to cover the new procedures.

Their effectiveness depends on the immune systems ability to replicate and elicits a response similar to natural infection.

Examples of live, attenuated vaccines include measles, mumps, rubella, MMR, yellow fever, varicella, rotavirus, and influenza (LAIV).

Artificial passive immunization is normally administered by injection and is used if there has been a recent outbreak of a particular disease or as an emergency treatment for toxicity, as in for tetanus.

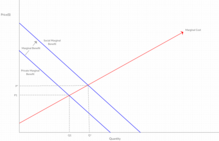

Society's undervaluing of immunizations means that through normal market transactions we end up at a quantity that is lower than what is socially optimal.

Measles is a good example of a disease whose social optimum leaves enough room for outbreaks in the United States that often lead to the deaths of a handful of individuals.

In these cases, the social marginal benefit is so large that society is willing to pay the cost to reach a level of immunization that makes the spread and survival of the disease impossible.

In order to internalize the positive externality imposed by immunizations payments equal to the marginal benefit must be made.

Since 1962 and the Vaccination Assistance Act, the United States as a whole has been moving towards the socially optimal outcome on a larger scale.

With fewer willing participants and a widening marginal benefit reaching a social optimum becomes more difficult for governments to achieve through subsidies.

Outside of government intervention through subsidies, non profit organizations can also move a society towards the socially optimal outcome by providing free immunizations to developing regions.

Without the ability to afford the immunizations to begin with, developing societies will not be able to reach a quantity determined by private marginal benefits.