Brexit

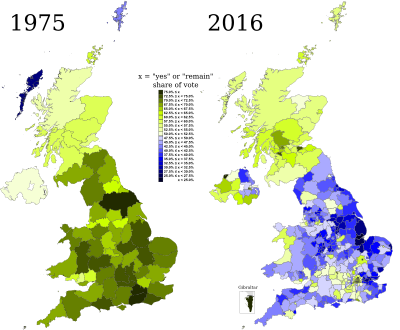

The Labour prime minister Harold Wilson's pro-EC government held a referendum on continued EC membership in 1975, in which 67.2 per cent of those voting chose to stay within the bloc.

Despite growing political opposition by a minority of UK politicians to further European integration aimed at "ever closer union" between 1975 and 2016, notably from factions of the Conservative Party in the 1980s to 2000s, no further referendums on the issue were held.

The Eurosceptic wing of the Conservative Party led a rebellion over the ratification of the treaty and, with the UK Independence Party (UKIP) and the cross-party People's Pledge campaign, then led a collective campaign, particularly after the Treaty of Lisbon was also ratified by the European Union (Amendment) Act 2008 without being put to a referendum following a previous promise to hold a referendum on ratifying the abandoned European Constitution, which was never held.

[8][9] Parliament approved the agreement for further scrutiny, but rejected passing it into law before the 31 October deadline, and forced the government (through the "Benn Act") to ask for a third Brexit delay.

[16] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term was coined in a blog post on the website Euractiv by Peter Wilding, director of European policy at BSkyB, on 15 May 2012.

[32] In October 1990, under pressure from senior ministers and despite Thatcher's deep reservations, the UK joined the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), with the pound sterling pegged to the deutschmark.

[40] Similarly, during the 2015 migration crisis, Chancellor Angela Merkel's decision to open EU borders and her request that member states share the burden of accommodating refugees sparked significant backlash.

[43] This success put pressure on the ruling Conservative Party, ultimately leading to Prime Minister David Cameron’s decision to hold the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum.

By linking perceived EU leadership overreach to concerns about sovereignty, Eurosceptic parties and media shaped public opinion in the UK, contributing to the referendum outcome.

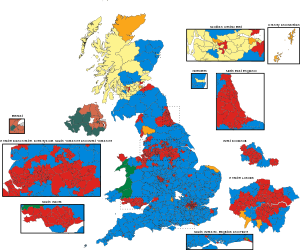

A 2017 study published in the journal Economic Policy showed that the Leave vote tended to be greater in areas which had lower incomes and high unemployment, a strong tradition of manufacturing employment, and in which the population had fewer qualifications.

[68][69][70] Studies found that the Leave vote tended to be higher in areas affected by economic decline,[71] high rates of suicides and drug-related deaths,[72] and austerity reforms introduced in 2010.

[83] In November 2017, the Electoral Commission launched a probe into claims that Russia had attempted to sway public opinion over the referendum using social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook.

[84] In February 2019, the parliamentary Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee called for an inquiry into "foreign influence, disinformation, funding, voter manipulation, and the sharing of data" in the Brexit vote.

[85] In July 2020, Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament published a report which accused the UK government of actively avoiding investigating whether Russia interfered with public opinion.

[98] On 29 March, Theresa May triggered Article 50 when Tim Barrow, the British ambassador to the EU, delivered the invocation letter to European Council President Donald Tusk.

[108][109] The result produced an unexpected hung parliament, the governing Conservatives gained votes and remained the largest party but nevertheless lost seats and their majority in the House of Commons.

[123] Following this partial agreement, EU leaders agreed to move on to the second phase in the negotiations: discussion of the future relationship, a transition period and a possible trade deal.

[150] On 18 March 2019, the Speaker informed the House of Commons that a third meaningful vote could be held only on a motion that was significantly different from the previous one, citing parliamentary precedents going back to 1604.

2) Act 2019, which received Royal Assent on 9 September 2019, obliging the Prime Minister to seek a third extension if no agreement has been reached at the next European Council meeting in October 2019.

The result broke the deadlock in the UK Parliament and ended the possibility of a referendum being held on the withdrawal agreement and ensured that the United Kingdom would leave the European Union on 31 January 2020.

[196] After the UK said it would unilaterally extend a grace period limiting checks on trade between Northern Ireland and Great Britain, the European Parliament postponed setting a date to ratify the agreement.

[206][208][209] A report published in March 2017 by the Institute for Government commented that, in addition to the European Union (Withdrawal) bill, primary and secondary legislation would be needed to cover the gaps in policy areas such as customs, immigration and agriculture.

[210] The report also commented that the role of the devolved legislatures was unclear, and could cause problems, and that as many as 15 new additional Brexit Bills might be required, which would involve strict prioritisation and limiting Parliamentary time for in-depth examination of new legislation.

[211] In 2016 and 2017, the House of Lords published a series of reports on Brexit-related subjects, including: The Nuclear Safeguards Act 2018, relating to withdrawal from Euratom, was presented to Parliament in October 2017.

[273][274][275] To forestall this, the EU proposed a "backstop agreement" that would keep the UK in the Customs Union and keep Northern Ireland in some aspects of the Single Market until a lasting solution was found.

The Act allowed for all devolved policy areas to remain within the remit of the Scottish Parliament and reduced the executive power upon exit day that the UK Withdrawal Bill provides for Ministers of the Crown.

The French and British governments say they remain committed to the Le Touquet Agreement, which lets UK border checks be completed in France, and vice versa (juxtaposed controls).

[323] Pharmaceutical organisations working with the Civil Service to keep medicine supplies available in the case of a no-deal Brexit had to sign 26 Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs) to prevent them from giving the public information.

[339] In December 2021, the Financial Times quoted a range of economists as saying that the economic impact of Brexit on the UK economy and living standards "appears to be negative but uncertain".

The response of British artists and writers to Brexit has in general been negative, reflecting a reported overwhelming percentage of people involved in Britain's creative industries voting against leaving the European Union.