Imperial Academy of Fine Arts (Brazil)

The foundation of art schools in Brazil came from, according to Rafael Denis, Francophile initiatives headed by the ministry of Dom João and the Conde da Barca.

It is unclear whether Dom João, the Marquis of Marialva, Lebreton, or French artist Nicolas-Antoine Taunay came up with the idea of bringing arts education to Brazil.

Within the group, there was a naval architect (Grandjean de Montigny), a mechanical engineer, a master ironsmith, carpenters, and various artisans in addition to traditional artists (including painter Nicolas-Antoine Taunay).

Theory: Practice: Lebreton also regulated the process and criteria necessary for student evaluation, the schedule of classes (which included outside subjects like music), and paired alumnists with public works projects.

Previously, the informal apprenticeship model, dating back to the medieval period, determined the status of artists based on the notoriety of their masters.

[7] Members of the Mission arrived in Brazil filled with high expectations, as Debret wrote: "We were all animated by a similar zeal and, with the enthusiasm of wise travelers that no longer feared facing the vicissitudes of a long and often dangerous voyage, we left France, our shared homeland, to go study an unknown environment and impress upon this new world the profound and useful influence—we hoped-- of the presence of French artists".

Despite royal support, the Mission, proponents of Neoclassicism, encountered resistance among native artists who still followed a Baroque aesthetic and already-established Portuguese professionals, who felt their positions were threatened.

The artists were able to survive on the pension granted to them by the government and supplemented their income by accepting commissions for portraits and organizing elite parties for the court.

His first official act as the director of the newly titled institution (then the Academia Real de Desenho, Pintura, Escultura e Arquitetura Civil) was to remove all members of the Mission group from their teaching positions.

Debret was named the official portrait artist for Dom Pedro I and Montigny was responsible for several architectural and urban planning that contributed to the renovation of the face of Rio de Janeiro.

[4] Lebreton, in turn, with the curriculum plan he established in 1816, left methodological guidelines that with some modifications remained guiding the evolution of the institution throughout the nineteenth century.

Silva suppressed courses in stone cutting, mechanics, and engraving, claiming that basic design instruction was sufficient for a country without artistic culture like Brazil.

In his memoirs about the early years of the AIBA, Debret lamented the end of the technical trades which, according to him, forced the institution toward, "the errors and vices of the ancien régime".

The exposition was decreed by the Emperor in a Ministerial Advisory on 26 November 1828, reading: The following year Debret and Grandjean de Montigny, with their own works and those of their students, presented forty-seven pieces of artwork, one hundred and six architectural designs, four landscapes, and four busts sculpted by Marc Ferrez.

[14] The reform also established a traditional academic system at the school, which was defined by the emulation of masters, the copying of famous works, and the mastery of basic tools of the trade.

[5] Despite constantly facing difficulties, in the second half of the nineteenth century the Imperial Academy reached its golden age under the dynamic (but brief) leadership of Araújo Porto-Alegre.

As the impact of the Industrial Revolution spread across the globe, interest in vocational and technical trades experienced a rebirth because they were seen as an important part of Brazil's modernization process.

He left his progressive and reformist intentions clear, stating: The "Quarry Reform" rebuilt much of Lebreton's original project, in relation to the valorization of technical courses and a curriculum as broad as it was profound for Academy students.

On the other hand, from that moment on the AIBA ceased being a simple preparatory center for artists and became actively engaged in the creation of a national identity consistent with the modernizing project of Dom Pedro II.

[15][19] The Academy eventually consolidated itself, with alumni becoming teachers and foreigners attracted into its circle, which stimulated cultural life in Rio de Janeiro and, by extension, throughout the Empire.

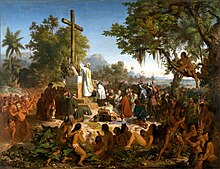

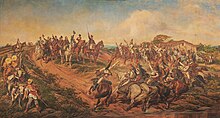

Artists, often commissioned directly by the government, produced a series of grandiose works, especially in painting, intended to visually portray a civilized and heroic past comparable to that of Europe.

Among the large number of artists during this period, Meirelles and Américo were the greatest of their generation, creating pieces that form part of collective national memory even today.

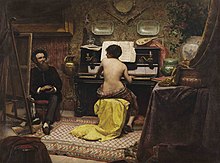

[5] Lesser known, though significant, works include: O Último Tamoio (1883), O Derrubador Brasileiro (1879), O Descanso do Modelo (1882), Caipira Picando Fumo (1893), and O Violeiro (1899).

Angelo Agostini ignited controversy in 1870 over national identity and the support of alternate artistic practices, as defended by George Grimm and his group.

[20] With the proclamation of the Republic, the old imperial Academy was converted into the "National School for the Fine Arts", under the direction of Rodolfo Bernardelli, who was already a professor of sculpture and artist laureate and highly respected by many influential members of the intellegencia.

The principles of modernism combated the predictable and routine aspects of artistic practices along with methodical, disciplined curriculums; they instead emphasized creative spontaneity and individual genius.