Imperial Roman army

In addition, Augustus established a new post of praefectus castrorum (literally "prefect of the camp"), to be filled by a Roman knight (often an outgoing centurio primus pilus, a legion's chief centurion, who was usually elevated to equestrian rank on completion of his single-year term of office).

Under the influence of Sejanus, who also acted as his chief political advisor, Tiberius decided to concentrate the accommodation of all the Praetorian cohorts into a single, purpose-built fortress of massive size on the outskirts of Rome, beyond the Servian Wall.

From the Second Punic War until the 3rd century AD, the bulk of Rome's light cavalry (apart from mounted archers from Syria) was provided by the inhabitants of the northwest African provinces of Africa proconsularis and Mauretania, the Numidae or Mauri (from whom derives the English term "Moors"), who were the ancestors of the Berber people of modern Algeria and Morocco.

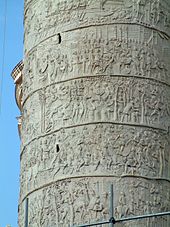

On Trajan's Column, Mauri horsemen, depicted with long hair in dreadlocks, are shown riding their small but resilient horses bare-back and unbridled, with a simple braided rope round their mount's neck for control.

To an extent, these units were simply a continuation of the old client-king levies of the late Republic: ad hoc bodies of troops supplied by Rome's puppet petty-kings on the imperial borders to assist the Romans in particular campaigns.

Compared to the subsistence-level peasant families from which they mostly originated, legionary rankers enjoyed considerable disposable income, enhanced by periodical cash bonuses on special occasions such as the accession of a new emperor.

In addition to constructing forts and fortified defences such as Hadrian's Wall, they built roads, bridges, ports, public buildings and entire new cities (colonia), and cleared forests and drained marshes to expand a province's available arable land.

The term came to be applied to auxiliary soldiers seconded to the staff of the procurator Augusti, the independent chief financial officer of a province, to assist in the collection of taxes (originally in kind as grain).

[91] According to Aurelius Victor, the frumentarii were set up "to investigate and report on potential rebellions in the provinces" (presumably by provincial governors) i.e. they performed the function of an imperial secret police (and became widely feared and detested as a result of their methods, which included assassination).

Typically, a newly appointed governor would be given a broad strategic direction by the emperor, such as whether to attempt to annex (or abandon) territory on their province's borders or whether to make (or avoid) war with a powerful neighbour such as Parthia.

For example, in Britain, the governor Gnaeus Julius Agricola appears to have been given approval for a strategy of subjugating the whole of Caledonia (Scotland) by Vespasian, only to have his gains abandoned by Domitian after AD 87, who needed reinforcements on the Danube front, which was threatened by the Sarmatians and Dacians.

These were much more expensive and time-consuming to erect, but were invulnerable to most natural threats (except earthquakes), provided much better protection against missiles and needed far less maintenance (many, such as Hadrian's Wall, would still be largely intact today if they had not been pillaged for their dressed stones over the centuries).

Speed in cleaning, closing and bandaging the wound was critical, as, in a world without antibiotics, infection was the gravest danger faced by injured troops, and would often result in a slow, agonising death.

In the Julio-Claudian era (to AD 68), conscription of peregrini seems to have been practiced, probably in the form of a fixed proportion of men reaching military age in each tribe being drafted, alongside voluntary recruitment.

[143] From the Flavian era onwards, it appears that the auxilia were, like the legions, a largely volunteer force, with conscription resorted to only in times of extreme manpower demands e.g. during Trajan's Dacian Wars (101–106).

[130] An indication of the rigours of military service in the imperial army may be seen in the complaints aired by rebellious legionaries during the great mutinies that broke out in the Rhine and Danube legions on the death of Augustus in AD 14.

The vast majority of the army's recruits were drawn from provincial peasant families living on subsistence farming i.e. farmers who after paying rent, taxes and other costs were left with only enough food to survive: the situation of c. 80% of the Empire's population.

In the class-conscious system of the Romans, this rendered even senior centurions far inferior in status to any of the legion's tribuni militum (who were all of equestrian rank), and ineligible to command any unit larger than a centuria.

Beyond these posts, the senior command-positions reserved for knights were in theory open to primipilares: command of the imperial fleets and of the Praetorian Guard, and the governorships of equestrian provinces (most importantly, Egypt).

It was apparently revived briefly by his successor Tiberius, whose nephews, the generals Germanicus and Drusus, launched major and successful operations in Germania in AD 14–17, during which the main tribes responsible for Varus' defeat were crushed and the three lost legionary aquilae (eagle-standards) were recovered.

However, the stiff, prolonged resistance offered by native tribes seemingly confirmed Augustus' warning, and reportedly led the emperor Nero at one stage to seriously consider withdrawing from Britain altogether;[217] and (b) Dacia, conquered by Trajan in 101–6.

Luttwak argued that annexations such as the Agri Decumates and Dacia were aimed at providing the Roman Army with "strategic salients", which could be used to attack enemy formations from more than one direction, although this has been doubted by some scholars.

According to Luttwak, the forward defence system was always vulnerable to unusually large barbarian concentrations of forces, as the Roman army was too thinly spread along the enormous borders to deal with such threats.

In addition, the lack of any reserves to the rear of the border entailed that a barbarian force that successfully penetrated the perimeter defenses would have unchallenged ability to rampage deep into the empire before Roman reinforcements could arrive to intercept them.

[227] Although this practice spared troops the toil of constructing fortifications, it would frequently result in camps often being situated on unsuitable ground (i.e. uneven, waterlogged or rocky) and vulnerable to surprise attack, if the enemy succeeded in scouting its location.

Camps could be situated on the most suitable ground: i.e. preferably level, dry, clear of trees and rocks, and close to sources of drinkable water, forageable crops and good grazing for horses and pack-animals.

[225] e.g. after their disaster on the battlefield of Cannae (216 BC), some 17,000 Roman troops (out of a total deployment of over 80,000) escaped death or capture by fleeing to the two marching-camps that the army had established nearby, according to Livy.

A detail of officers (a military tribune and several centurions), known as the mensores ("measurers"), would be charged with surveying the area and determining the best location for the praetorium (the commander's tent), planting a standard on the spot.

One tablet probably contains a scathing report by an officer (himself probably a Rhineland German) about the progress of young local trainee cavalrymen in the cohors equitata: "on horseback, too many of the pathetic little Brits (Brittunculi) cannot swing their swords or throw their javelins without losing their balance".

[272] From the 2nd century onwards, Eastern mystery cults, centred on a single deity (though not necessarily monotheistic) and based on sacred truths revealed only to the initiated, spread widely in the empire, as polytheism underwent a gradual, and ultimately terminal, decline.